In the last two weeks of February, humanitarian agencies reported 895 cases of conflict-related rape as M23 rebels advanced through the eastern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC). According to a United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees official, this was an average of more than 60 rapes a day.

UNICEF officials reported similarly grim figures. Between Jan. 27 and Feb. 2, 2025, the number of rape cases treated across 42 health facilities in DRC jumped five-fold, with 30 per cent of these cases being children.

While immediate responses are needed to stop the violence, provide health care to the survivors and assist the displaced, the pursuit of justice also plays a critical role.

Investigative bodies, including the International Criminal Court (ICC), are increasingly using technology to investigate conflict-related sexual violence. In a recent research project, my team interviewed experts who specialize in conflict-related sexual violence investigations around the world.

The ICC’s chief prosecutor, Karim Khan, visited DRC at the end of February and met with sexual violence survivors. The ICC has the mandate to investigate rape, sexual slavery and other gender-based violence amounting to genocide, crimes against humanity and war crimes. The office had reactivated investigations in October 2024.

Investigators start by speaking to survivors, following guidelines such as the 2023 Policy on Gender-Based Crimes or the Global Code of Conduct for Gathering and Using Information About Systematic and Conflict-Related Sexual Violence. The Global Code of Conduct is known as the Murad Code after Nobel Peace Prize recipient and advocate Nadia Murad.

In our research, we found that survivors of conflict-related sexual violence are connecting with investigators through various technologies, such as directly using encrypted apps like Signal. Survivors also go through civil society organizations equipped to take video or electronic statements — Yazda, for example, which works with Yazidi survivors of ISIS crimes in northern Iraq — or via portals like the ICC’s OTPLink. The UN’s Commissions of Inquiry also encourage and receive email submissions.

International courts and investigative bodies are also analyzing open-source information on conflict-related sexual violence, such as videos, photos and statements posted on online platforms. Guided by the Berkeley Protocol on Digital Open Source Investigations, this information can be useful to support witness statements, place alleged perpetrators at the scene of the violations and link incidents into a pattern of similar violence.

For example, the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria described how ISIS used the encrypted app Telegram and other online platforms to buy and sell captured Yazidi women and girls across the Iraq-Syria border to sustain its sabaya (sexual slavery) system.

In Ukraine, our study found that the main technology-related concern in open-source data gathering is identifying AI-created and other artificially generated images, specifically designed and planted in the public domain as a form of disinformation or to compromise investigations.

Conflict-related sexual violence is often perpetrated indoors which makes certain technologies like satellite or drone imagery less useful. However, other forms of technology have proven to be beneficial in Ukraine’s investigations. In particular, face and voice recognition software have supported efforts to identify alleged perpetrators.

While Ukraine’s experience points to some successes, investigations into sexual violence committed by ISIS in northern Iraq have been hampered. This is partly due to the lack of automated translation software in the Yazidi language to facilitate the transcription and translation of testimonies.

This speaks to the importance of developing software to translate minority languages spoken in armed conflict zones.

Survivors have expressed concerns about the turn to the digital. They fear that their identities and experiences may be revealed through hacking or poor data handling, which could put them at risk of reprisals from perpetrators or their accomplices. It could also lead to stigmatization and ostracization in some communities, undoing survivors’ efforts to rebuild their lives.

To address these concerns, international courts and investigative bodies have adopted data protection protocols. However, the lack of a standardized framework for the use of technology in the investigation of conflict-related sexual violence remains a significant concern for the investigators we interviewed.

Such a framework would incorporate best practices in supporting survivors providing evidence, tracking and preserving open source information and developing new technological applications.

If there is to be justice for survivors of conflict-related rape in DRC and elsewhere, technology — provided it is used with great sensitivity — will likely be an important and timely aid.

This article originally appeared in The Conversation.

In early 2025, the March 23 Movement (M23) armed group seized control of Goma and then Bukavu, two major cities in the eastern Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). M23’s continuing advance in eastern DRC, in defiance of ceasefire agreements, has terrorised communities and led to mass displacement. The M23 group is a major non-state armed group, but had been relatively inactive in recent years prior to a rapid escalation of violence in 2022, which hit new crisis levels in early 2025 with the capture of the two cities. Over two million people have since been internally displaced in eastern DRC; close to one million people were displaced in 2024 alone.

As Angola and other regional actors attempt to mediate peace talks, civilians are caught in a devastating humanitarian crisis, one of the most critical parts of which is sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV). This not only contributes to displacement, but displaced women are also more at risk of SGBV. Furthermore, signs point to gendered violence worsening: in just the last two weeks of February 2025, UNHCR reported 895 reports of rape made to humanitarian actors.

In order to understand these risks, in December 2024, researchers with the Congolese organisation Solidarité Féminine Pour La Paix et le Développement Intégral (SOFEPADI) interviewed 89 displaced women and 30 civil society organisations working in internally displaced person (IDP) camps around Goma. The overwhelming majority of respondents had experienced or witnessed SGBV; while interviewers were careful to avoid direct questions so as not to induce trauma, dozens of women nonetheless disclosed personal experiences. These interviews show just how vulnerable the population is, and how an already dire situation for women and girls has been made exponentially worse over the past six months. This blog outlines some of the key findings of the forthcoming research report.

The risks and drivers of displacement

Displaced women were extremely likely to have experienced conflict-related SGBV: 97% of those interviewed were victims of or had witnessed violence during the conflict, with some stating that sexual violence had contributed to their displacement. One IDP camp resident stated:

“I was living in Kitshanga and then the war started, but I didn’t leave right away. One day I went to the field and I was raped. That’s the day I left Kitshanga and I came here [to the camp]”.

Members of community organisations working in the IDP camps identified an increase in the perpetration of sexual violence over the course of the conflict, with more women arriving to the IDP camps having suffered sexual violence than earlier in the war. Many women also explained they had witnessed killing and massacres in their home communities. Some women had lost close family members or had themselves been wounded in the fighting.

The vast majority of respondents—over 70% —identified M23 as the direct cause of their displacement. A further 5% indicated that their displacement had been caused by Rwanda’s armed forces, either alone or in conjunction with M23. One woman from Kitshanga, a town over 150km away from Goma, stated that she had been displaced to the IDP camp following “massacres, rapes, and the war…caused by the M23”.

Perpetrators everywhere, protection nowhere

M23 troops were not the only group identified as being responsible for perpetrating SGBV during displacement and in the camps. The crisis has led to widespread gender violence perpetrated by armed groups and forces, including the Congolese military and military-allied militias, civilians, and groups of bandits.

Despite the significant number of international forces operating in eastern DRC, which includes the UN peacekeeping mission, MONUSCO, The South African Development Community mission, and, previously, the East African Regional Force, both civil society representatives and displaced women expressed little confidence in these forces’ ability to prevent SGBV. Goma remains the operational centre of the MONUSCO mission. Yet of the 89 displaced women interviewed, only one identified MONUSCO troops as a group as providing security in the areas surrounding the camps. This is despite MONUSCO being a named option in the interviews. In the eyes of most of the respondents, international forces are simply absent.

Scattered survivors and thwarted justice

Since the M23 takeover, international attention has been drawn to the crisis, and there is renewed focus on by the International Criminal Court on combatting impunity and securing accountability for atrocity crimes. Organisations on the ground, however, remain under-resourced and over-stretched. Access to healthcare (including mental health support), economic support, children’s education, and justice are all severely constrained – a point consistently emphasised by affected women interviewed. Repeated displacement of vulnerable people, including SGBV survivors, is likely to further frustrate attempts at holding responsible actors to account.

With the recent order from M23 for civilians to leave IDP camps, already uprooted women are displaced once again, with little access to humanitarian aid. Civilians have been dispersed, with many unable to return to their villages due to fighting. This repeated displacement and dispersal of vulnerable women has made it near-impossible to track where women are going, to provide necessary and ongoing support, and to record reports of future SGBV cases.

The need for action

The security situation in eastern DRC is shifting rapidly, and the context that these interviews took place in only three short months ago has changed. What remains consistent, however, are high levels of forced displacement, SGBV, and an internationalised conflict that has worsened women’s security. The data is clear: responses to this dire security situation, with women and girls uniquely and disproportionately impacted, must include and urgent and durable ceasefire and increased humanitarian support. Immediate steps must be taken to alleviate humanitarian suffering, to protect women and girls from further SGBV, and to move toward a peaceful resolution that results in Congolese civilians able to return to their homes and begin the process of recovering from this devastating conflict.

*SOFEPADI (Solidarité Féminine Pour La Paix et le Développement Intégral) is a Congolese NGO which has been working for 25 years to promote and defend the rights of women and girls in DRC: through prevention of gender-based violence, skills training, medical and psychological support, and legal services for SBGV survivors. The authors worked with a team of researchers from SOFEPADI, coordinated by Martin Baguma and SOFEPADI Executive Director Sandrine Lusamba, and with research assistance from Cora Fletcher, an MA student at Dalhousie University. This brief would not have been possible without their collaboration.

Uganda, a model for refugee management?

Uganda is widely cited as a model country for the hospitality and integration of refugees having implemented an open-door policy and refugee self-reliance approaches since 1999.1 Currently, Uganda has the world’s third-largest refugee population, with over 1.7 million refugees, the majority of whom are women, mainly from South Sudan, the Democratic Republic of Congo, and other countries such as Rwanda, Burundi, Somalia, Sudan, and Eritrea as of December 2024.2 Once in Uganda, refugees are allocated land in settlements for shelter, but also farming to get food for home consumption or to earn an income. In the spirit of self-reliance, refuges access public services such as health care, education, water, and land with host communities.

Refugee Welfare Committees (RWC) as a forum for participation

In line with its often praised progressive approach and open-door policy for refugees, Uganda has established a refugee-led leadership structure known as Refugee Welfare Committees (RWCs) in all refugee settlements, including Nakivale and Oruchinga, to ensure that refugees participate in community programs and critical decisions that shape their lives. These committees, based on the Refugee Act of 2006,3 operate on three levels: RWCI (clusters), RWCII (zones/villages), and RWCIII (entire settlement). Elections are held every two years. RWCs are the formal representative body for refugees, ensuring protection and access to justice. RWCs are the first point of contact for issues and communicate with the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), UNHCR, local authorities, aid agencies, and host communities. Each RWC level runs a committee with various secretariats for sectors such as finance, health, and education. Originally intended to foster relations between refugees and nationals, RWCs in Uganda have become crucial for enhancing service delivery, community organization, identity, and political participation among refugees.

Challenges to women’s participation in decision-making

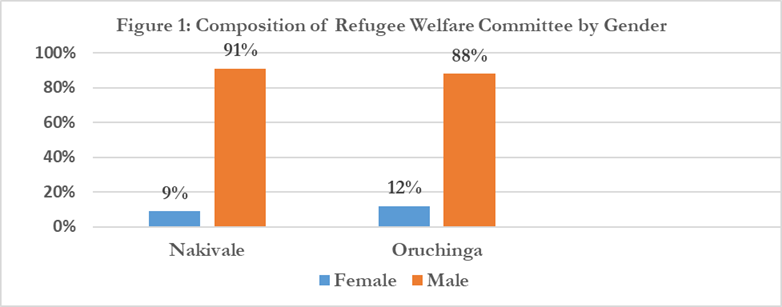

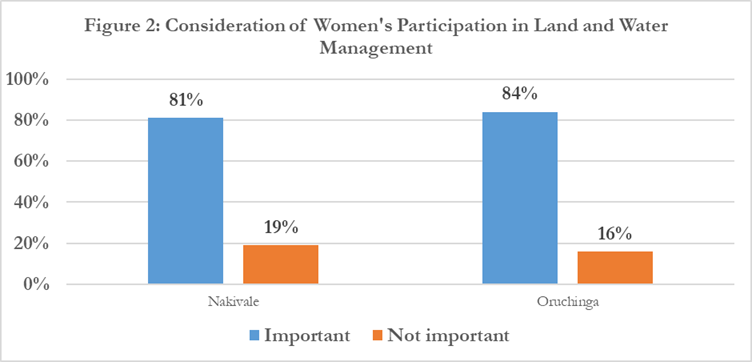

While the formation of RWCs in Uganda aims to promote inclusive leadership, it does so without addressing systemic gender challenges to participation in decision-making processes. The RWC guidelines assume that women and men are able to compete on the same footing for elective positions. This assumption is far from reality given the socio-cultural challenges faced by women. Research carried out in Nakivale and Oruchinga refugee settlements located in Southwest Uganda in April 2024 showed the limited involvement of women in RWCs (see Figure 1). Despite limited participation, women’s participation is still perceived as important (see Figure 2).

Explanations for the low representation of women in RWCs fall into institutional, cultural, and individual factors. Institutional factors are largely related to the gender-neutral legal framework of the RWC, which does not explicitly encourage women’s participation; for example, there are no gender quotas or monitoring mechanisms to ensure women’s participation. In addition, social and cultural factors – such as gender stereotypes and socially ascribed roles that make women responsible for children, the elderly, and domestic work – hinder women’s participation. As a result, women are often overburdened and do not have time to fully engage in decision-making processes. Women and girls face challenges related to harmful practices such as early and/or forced marriage, and unequal access to, or control over, services and resources. Girls are often pushed to drop out of school and help with household chores. Sexual gender-based violence and reproductive health-related factors including rape, sex slavery, and forced pregnancy, lower their self-esteem and confidence to participate in public life. Systemic institutional and cultural challenges lead to significant gender disparities in property ownership and greatly hinder women’s participation. These challenges particularly affect women’s education, especially their literacy skills, which are essential for leadership roles. Consequently, women are often at a disadvantage compared to their male counterparts. A female refugee observed, “If a girl is not in school, she is expected to get married, regardless of age.” Another noted, “Being a woman is restrictive enough, and when you add being a refugee, [it] is a double tragedy” (KII and FGDs).

Women at the frontlines of water and land conflicts

Since water and food provision are among the roles socially ascribed to women, they are often at the risk of water and land conflicts. Women engage in water collection for household use. Water collection can be arduous: travel to and from water sources, and waiting in queues, can take hours, and the distance is often covered on foot. They are exposed to conflict risks: verbal and physical fights are not unknown at water collection points.

Women also engage in subsistence farming and firewood collection – these resource generation and gathering activities can come with the same risks as water collection.

Empowering women in land and water management

Over half of all refugees are women and girls, yet their voices are visibly missing in decision-making on the affairs that affect their day-to-day lives. Lack of women’s participation in water and land decision-making negatively impacts their daily lives by perpetuating gender inequalities and stereotypes, hindering access to resources, and limiting their ability to shape water and land related policies and laws that directly affect them. This short-coming is critical considering women’s involvement adds value to resource management, results from the research suggest that the gender of the household head has the highest positive effect on household water provision, with more female-headed households paying water user fees than male-headed households. The presence of women in RWCs also increases the information flow and awareness among women in the larger settlement. Women leaders experience challenges at home and community and therefore understand the unique challenges other women experience daily (KII, Nakivale). The importance of women’s participation is further underscored by evidence that women tend to be better custodians of water and better land use managers, precisely due to their socially ascribed roles and dependence on these resources.

A way forward

Since women are most affected by land and water conflicts, and have a higher stake in water provision and household food security, their voices need to be heard in decision-making. Gender-responsive and inclusive management policies should be implemented as a step towards social cohesion, better resource use, and improved service delivery. Leveraging women’s participation in refugee leadership broadens their horizons, enabling them to support themselves and their communities. It ensures that services and policies are informed by women’s voices and experiences, aligns humanitarian efforts with gender-specific needs, and equips women with skills for future reintegration into their home countries or relocation to new ones.

Hence, there is a need to deliberately use affirmative action, including quotas, to support women’s involvement. Therefore, gender-responsive and inclusive guidelines, such as clearly defined quotas in RWCs, are crucial to facilitate women’s participation. The majority are refugees are women, who are better understood and advocated for by women leaders who share their daily experiences. Moreover, there is evidence that having more women in decision-making positions increases the level of public sector effectiveness and accountability.4 This is particularly relevant in Uganda as the country seeks to enable and encourage refugee self-governance.

In 2016, the Colombian government signed a historic peace agreement with guerilla group the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia, also known as FARC. The agreement brought an end to 52 years of war, but today, eight years after the agreement was ratified, Colombia is still not at peace.

In this episode, Dr Nafees Hamid and Dr Andrés Casas discuss the motivations of guerilla group members in Colombia, public attitudes towards the 2016 peace agreement, and how behavioural science can facilitate peacebuilding efforts.

Since 2019, the number of people attempting to flee Lebanon via irregular boat crossings has drastically increased. Driven by compounding political, economic and security crises, Lebanese citizens are now increasingly joining Syrian and Palestinian refugees attempting the sea crossing to Europe.

As the Lebanese Armed Forces’ (LAF) consolidates its control over Lebanon’s borders, and with a new, reform-oriented government in place, now is the time to think more broadly about how security resources are allocated. While the international community has primarily focused its attention on reinforcing the LAF’s capabilities, there has been significantly less discussion about how the state may relieve the LAF of its non-military responsibilities as part of a wider shift towards improved security sector cooperation and long-term sectoral resilience.

One area for reform is Lebanon’s management of irregular maritime migration – attempts to cross to Europe in boats without the requisite travel documentation. With a new reform-focused government in place, the country has an opportunity to craft a more sustainable national framework to address sea crossings as a humanitarian challenge – not solely as a security issue – managing this through a whole-of-government approach that includes the police, social ministries, and civil society organisations. Addressing the root causes of social problems that lead many to migrate must be seen as a priority, rather than further militarising migration governance.

The rising tide of desperation

Irregular maritime migration from Lebanon has surged in recent years – while only 200 individuals landed in Cyprus in 2019, by 2023 this figure had jumped to over 5,000. In the first half of 2024 alone, nearly 3,300 people attempted to leave Lebanon by boat. While there has been a ‘low but steady’ return of Syrian refugees following the collapse of the Assad regime, many factors still prevent a mass return to Syria. Sea crossings are continuing, and this includes many desperate Lebanese citizens, driven by overlapping crises in the country to seek a better life elsewhere, with a sense of hopelessness unlikely to change in the near term. In interviews conducted for the research this blog draws from, many see irregular boat migration as their only option, with land routes also presenting logistical and security risks.

A military stretched thin

In tandem with its role managing increasing security threats across the country, the LAF leads on managing irregular maritime migration from Lebanon. The armed forces are already stretched as they respond to threats on land: the LAF has frequently been deployed on the eastern border with Syria; in February, a further 1,500 troops were deployed along the southern border with Israel to reinforce the approximately 4,000 already stationed there. This is only about half the troops Lebanon agreed to deploy in the south as part of the US brokered ceasefire deal.

Alongside discussions about increasing military resources, Lebanon’s political transition offers an opportunity to strategically allocate security resources and ensure that the military is not overburdened with duties better suited to either the police or social ministries. With a new government in place and Joseph Aoun, the former LAF commander, as President, the country has a unique opportunity to shift its approach to both national and human security, and reviewing maritime migration governance falls under this pivot.

A security-first approach isn’t working

The prevailing ‘security-first’ approach to governing maritime migration frames boat crossings as a national security threat to Europe, rather than as an entrenched humanitarian issue. Treating migration as something to be militarily deterred misses the deeper political and economic forces that drive people to leave the country. Without a holistic political and socio-economic solution, people will continue to flee in the desperate search for a better life.

International donors have directed a large number of resources to bolster the capacity of the LAF to control borders. In May 2024, the EU earmarked €200 million to strengthen the LAF’s border management efforts, including its capacity to oversee the maritime border and manage attempted boat crossings to Cyprus or Italy. Interviews for this research, however, revealed that the over-prioritisation of the army in foreign-funded security interventions comes at the expense of the wider Lebanese security sector. Other domestic agencies (namely the Internal Security Forces and the General Security Office) play a key role in internal safety and security but are less able to meet their mandates in a manner that complements the LAF’s activity because of asymmetrical resourcing, training and equipment challenges.

The dominance of security-first approaches has not only ignored the underlying drivers of migration, particularly economic factors; it has also obscured critical human rights concerns. With new internationally funded radars and boats, interceptions at sea may have increased, yet there is little oversight over what happens to migrants. Meanwhile, reports suggest that migrants can be detained or face deportations. Humanitarian actors working directly with affected Syrian and Lebanese communities also remain largely excluded from decision-making. To ensure a rights-based approach, internationally funded border security programmes should engage with these humanitarian actors in the consultation, design, implementation and monitoring of programmes.

A call for balance

The new government in Lebanon, led by President Aoun, is in a unique position to re-evaluate Lebanon’s security strategy. As the former commander of the LAF, he will have seen first-hand how the underfunding of Lebanon’s police and other civilian security bodies undermines their capacity to support the army. By developing a more balanced approach to migration that integrates human rights, legal protections, and a focus on the socio-economic drivers of migration, resources can be more effectively used.

Lebanon’s reform process needs a national security strategy that empowers law enforcement agencies to fulfil their mandates – an approach that would enhance border management while relieving the LAF of non-military responsibilities. This would free up military resources to focus on critical priorities such as establishing a monopoly of violence and a deterrent against Israel in the south of Lebanon, and working toward the implementation of UN Security Council resolution 1701. The President has already called for a comprehensive defence and security policy: as he moves forward with this, ensuring that maritime migration governance is included in a broader security recalibration is vital. If Lebanon can achieve this, it will not only improve maritime migration management but also build a more effective, balanced, and sustainable security sector for the years ahead.

Christianne Aikins and AnnaSophia Gallagher work on security sector reform and research projects at Siren Associates, which helps organisations remove barriers to safety, justice and freedom. Siren works across the security, public, and social sectors, using research, change management and digital innovation to build their partners’ responsiveness, efficiency, and impact.

The fall of the Assad regime in December 2024 was met with widespread relief – not only among Syrians but among regional actors eager to move past its destabilizing, criminal enterprises. Hopes were highest that Syria’s trade in Captagon – the highly addictive drug that, under Assad, flooded regional markets via Jordan – would come to an end.

While the regime’s collapse has disrupted the drug trade, narcotics trafficking persists. This is a reflection of the ability of Syria’s smugglers to adapt, taking advantage of the country’s porous borders, entrenched supply chains, sustained regional demand, and the trade’s enduring profitability in a fractured economy. Without a comprehensive strategy to tackle these underlying drivers, drug smuggling will likely remain entrenched in Syria’s post-Assad landscape.

A state-built drug empire

Since 2019, officials believe that Assad regime played a central role in the Captagon trade, turning Syria into a major hub for drug production and smuggling. This illicit enterprise was highly organized, involving state institutions, military resources, and illicit networks. ‘It’s reported that h-ranking officials and military officers oversaw Captagon production and trafficking, often working with Lebanon’s Hezbollah and organized crime groups to expand distribution networks. According to the Syrian organization Etana, in June 2023, 79 per cent of Suwayda’s drug network and 63 per cent of Daraa’s were linked to Syrian military intelligence. Factories were strategically located in regime-controlled areas – particularly in rural Damascus, Homs, and Latakia – where they operated with security and efficiency.

What began as a small-scale operation evolved into a multibillion-dollar industry, sustaining patronage networks, generating illicit revenue, and pressuring neighbouring states by flooding their territories with drugs. With most trafficking routes running through Daraa into Jordan, the province became a critical gateway for Syria’s expanding role in the regional drug trade, fuelling state tensions with its neighbours.

Smuggling operations in a post-Assad Syria

Despite the collapse of Assad’s regime, Syria’s drug trafficking networks remain active. According to Etana, at least 25 cross-border smuggling attempts into Jordan were recorded between Assad’s departure on 8 December and mid-January, with 14 occurring since the start of 2025. Though significantly lower than the 65 attempts recorded by the same organization during the same period in 2023–24, the continued smuggling underscores the resilience of these networks.

This resilience is unsurprising given the ability of the drug traffickers to adapt quickly. Despite losing state protection, Syria’s smugglers have swiftly exploited the power vacuum left by the regime’s fall. Taking advantage of weak security control, they have relocated drug-related assets to safeguard Captagon production equipment, and stockpiled supplies. Reports indicate that traffickers also looted narcotic materials and machinery from regime sites, particularly those linked to military intelligence and the 4th Division in southern Syria and rural Damascus.

In addition to securing production infrastructure, trafficking networks have maintained access to significant stockpiles of narcotics accumulated before the regime’s collapse. These reserves allow smugglers to sustain operations despite political upheaval. Moreover, it’s claimed that continue to source additional narcotics – especially hashish and crystal meth – from Lebanon and Iraq to compensate for any supply disruptions.

Beyond preserving their supply chains, Syria’s smugglers have also enhanced their operational capacity. News reports showed that pro-regime forces hastily fled southern Syria, this enabled traffickers looted abandoned military bases and weapons depots, securing firearms and military-grade equipment. This has strengthened their ability to provide armed cover for cross-border smuggling operations, making counter-trafficking efforts riskier and more difficult.

Diverse smuggling tactics

Smugglers have continued to diversify their methods, using a range of tactics to evade detection. Recent trafficking attempts include moving drugs on foot through remote illegal crossings, particularly when weather conditions allow. Smugglers are also increasingly using drones, which are widely available in southern Syria – even in mobile phone shops – where they sell for between $4,000 and $8,000. Their accessibility has made it easier for traffickers to transport small quantities of high-value, low-weight drugs such as crystal meth.

This combination of tactics has reportedly enabled smugglers to maintain a success rate similar to pre-collapse levels. According to Etana, eight of the total smuggling attempts so far have been successful, reflecting a 32 per cent success rate. The profitability of these operations, combined with Syria’s fragile economy, will continue to drive the drug trade as a key source of income. Weakened by years of conflict, heavy international sanctions, and limited economic opportunities, the country’s recovery is likely to remain slow and difficult, even in a post-Assad era. With few legitimate job prospects, many young men could be drawn to the illicit economy as a lucrative and appealing livelihood, further entrenching Syria’s role in regional narcotics networks.

Limited enforcement capacity

The limited capacity of the new Syrian authorities has further enabled traffickers to exploit security vulnerabilities. HTS’s rapid takeover of vast territories following the regime’s collapse has severely strained its resources, weakening its ability to maintain a centralized command structure for border security. As a result, many former regime posts along the Syrian–Jordanian border are now manned by local factions that lack the necessary resources and coordination for systematic monitoring. This has, in turn, provided smugglers with greater operational freedom, particularly in remote areas.

Similarly, the new authorities’ limited capacity has hampered efforts to implement systematic counter-narcotics operations. While they have uncovered industrial-scale narcotics production and packaging facilities in various locations, including in rural Damascus, these detection efforts remain inconsistent – especially in curbing smuggling into Jordan. Without a coordinated and sustained domestic approach, traffickers will continue to exploit gaps in enforcement, ensuring the resilience of the illicit drug trade.

The evidence strongly suggests that while Assad’s fall has disrupted Syria’s drug trade, it has not eradicated the country’s role in regional narcotics trafficking. Addressing this issue requires sustained international cooperation, enhanced border security measures, and targeted economic development programmes to provide viable alternatives to smuggling.

Efforts must also focus on reducing regional demand for narcotics, as continued profitability remains a core driver of the trade. Without a comprehensive and coordinated strategy, Syria’s post-Assad landscape will remain vulnerable to the influence of illicit drug networks, perpetuating instability both within the country and beyond its borders.

This article originally appeared on Kalam, the website of Chatham House’s Middle East and North Africa Programme.

Content warning: This article contains discussion of sexual violence, including direct quotes from survivors.

“I came to South Sudan in June 2024. The cause of my journey was the conflict in Sudan. When we reached the bush, our vehicle was stopped [and] some women were asked to come down; they were sexually harassed. Young girls, under 18 years old, were abducted – two of them were from my husband’s family. On the border of South Sudan, people were well-treated. However, the challenges facing women and girls in the camp is lack of shelter, sanitary facilities, food, schools, and health facilities. I think coming to South Sudan harmed me more because I don’t have anything to eat, no household, and my husband went back to look for those abducted girls. He has now stayed for three months without communication to me. I wonder whether he is alive.”

Displaced woman in South Sudan, interviewed August 2024

War erupted in Sudan in April 2023, leading to widespread forced displacement, extreme rates of sexual and gender-based violence (SGBV), destruction of homes and property, and mass killings. To date, approximately 1 million people have crossed the Sudanese border into South Sudan in search of safety. Many of these are ‘returnees’, people who originally migrated to Sudan due to the South Sudanese war (2013-2020). Now, having been repeatedly displaced in both directions across the border between Sudan and South Sudan, returnees and refugees alike are struggling to survive in highly constrained and challenging conditions, while the repeated physical and mental trauma they endured in both South Sudan and Sudan remains unaddressed.

UNHCR map of displaced persons in South Sudan

In July 2024, our team launched a research project aiming to understand the experiences of those forcibly displaced from Sudan to South Sudan. We were especially concerned with the high rates of SGBV reported, the role that SGBV played in displacement, experiences of SGBV during flight, and risks of gendered violence in the South Sudanese settlements. Using ‘sensemaking’ methodology, the STEWARDWOMEN team worked on the border of Aweil North for two weeks, gathering stories and participants’ self-interpretation of these stories to better understand links between SGBV and forced displacement, and to uncover the most pressing needs of those living in precarity along the border.

This post is based on 695 shared narratives shared by displaced people in Aweil North, South Sudan. It centres the observations and analyses of STEWARDWOMEN researchers, who put their own comfort, well-being, and safety on the line to bring forward the voices of those whose most pressing survival needs are not being met and who have had few opportunities to share their stories.

Sexual and gender-based violence during forced displacement

It was when life became difficult and threatening in Sudan day and night that we decided to leave for South Sudan. (displaced woman in South Sudan, interviewed August 2024)

Rampant violence was what led most participants to leave Sudan and make the journey to South Sudan. This included SGBV, which over half of participants said was a big factor in their decision to journey across the border. Participants described rape, gang rape, abduction for forced marriage and sexual slavery, along with beatings and killings, as threats to their well-being and safety. It was not uncommon for women to describe extreme sexual violence that upended social norms. One STEWARDWOMEN researcher was told of a situation in which a very old woman, a grandmother, was gang-raped by youth who looked to be the same age as her grandsons. The rape itself was traumatic enough, but the young age of the perpetrators also signalled a breakdown in age-related social norms that shook this woman deeply. She was not the only woman to share similar experiences:

“As I started my journey, I was in the bus with women and other men. Towards the border line we were stopped by a group of other men and were told to get out of the bus. Women were taken to the bush and I was left aside. A young boy forcefully put a gun on my head and told me to undress, A boy I can call my grandchild did that to me at my age of 65 …if I think of it, I can’t even eat food.”

Displaced woman in South Sudan, interviewed August 2024.

“On the way [to South Sudan], I witnessed a lot of bad things which happened to women/girls. We travelled in a convoy of 5 vehicles with many people – women, children, men and youths. The vehicles were ambushed, drivers were put under gun points and all the passengers were ordered to come down. After all people were forced down, the rebels started to sort people girls from 12 yrs and above and women of 20 – 45 yrs were abducted. The youth of 10 yrs and above were also abducted for recruitment into the army.”

Displaced woman in South Sudan, interviewed August 2024.

Many participants described how their families were torn apart during the journey from Sudan to South Sudan, and stated they did not know where their loved ones were:

“We started our journey walking on foot, it was me, my daughter and my husband. They grabbed my daughter and took her to the forest and they started raping her so my husband decided to go and rescue her and he and my daughter didn’t return from the forest. I waited for them and when I wanted to follow them I was stopped by other women because they said it is not safe. I cannot sleep at night because I don’t know if they are safe or dead.”

Displaced woman in South Sudan, interviewed August 2024.

“When we were travelling on the way, we entered an ambush of militia who abducted my 14 years old sister…. I was seriously crying but it never helped.”

Displaced woman in South Sudan, interviewed August 2024.

Life in the South Sudanese temporary settlements

In the Aweil North temporary settlement, the STEWARDWOMEN team found conditions that could only be described as shocking. Refugees and returnees are meant to stay in this area for only a short time until they are resettled by the International Organization for Migration (IOM), but many people had been there for three months or longer. Some had been registered as refugees or returnees, others had not. All were struggling to survive without adequate food or shelter, and with no access to desperately needed healthcare. Because of looting and robbery on the road, many arrived without any food, clothing, or supplies. At the time the STEWARDWOMEN team met them, they had been left for months with almost no support.

A makeshift reed and tarpaulin shelter in a transit settlement. Credit: STEWARDWOMEN.

The team visited the area during the rainy season; much of the area was flooded and people were wading through water. Without access to toilets or sanitary facilities, people’s dignity had been further eroded, and the risk of disease was extremely high.

“Women and girls living in Kirradem boarder entry point settlement area are at risk of diseases as they live in a water flooded settlement. There is no safety and healthcare services for women and girls in the area. They lack dignity kits and personal hygiene is a big concern. As women leaders in the settlement camp, we don’t see support coming for women and girls. They are sleeping in flooded shelters and many children have died of measles and malaria. There is no safety for women and girls in the settlement.”

Displaced woman in South Sudan, interviewed August 2024.

The closest comprehensive health facility is well over 100 km away in Aweil Centre. This is where SGBV survivors must go to access most healthcare services, including sexual and reproductive healthcare, yet many people living in this area have suffered injuries that make this trek impossible. STEWARDWOMEN put out calls to open up referral pathways to find support, but with extremely limited services available in the region, few safe or maintained roads, and resources diverted elsewhere, there were no viable options to secure support for those sheltering in this area.

Along the newest border in the world, important distinctions are being made between ‘returnees’ and ‘refugees’, with vulnerabilities identified for both groups. Returnees face discrimination by the community, often being told that they “chose to go to Sudan, why are you coming back here?” Refugees feel unsafe and vulnerable, related in large part to long-established regional and ethnic tensions that fueled the split of South Sudan from Sudan in 2011. Women and girls who have been raped face further stigma, often labelled “wives of rebels of Sudan”. With registration and resettlement sporadic, refugees and returnees alike live in a liminal state, without community or support in South Sudan and unable to go back to Sudan.

What needs to be done

“Unless we receive support from the government and NGOs, many of the women and girls will opt to return to Sudan.”

Displaced woman in South Sudan, interviewed August 2024.

Increased aid and humanitarian support are urgently needed in Aweil North. The STEWARDWOMEN team encountered many graves in and around the settlement, including the graves of children who had died from illness, injury, or malnutrition. The situation in the settlement is dire, with many displaced people sleeping under trees and in makeshift shelters, without even a carpet or a tent. Humanitarian agencies and the South Sudanese government must spread efforts out along the entire border region: wherever people cross, humanitarian needs are high.

Resettlement efforts must be increased and people moved out of the transit centres quickly. Transit centres should also be moved to areas less prone to flooding, and, at a minimum, temporary and emergency health facilities should be built and staffed. Virtually all respondents had suffered physical and emotional trauma; therefore, medical care and psychosocial support are critical needs.

Following rape, witnessing loved ones killed, losing homes and possessions, those displaced from Sudan now endure dire living conditions and a near total absence of support. The displaced persons showed generosity and courage in telling us what they have endured. Their suffering is a call to action—it is our collective responsibility to respond, with urgency and compassion.

1 February 2025 marked the fourth anniversary of the 2021 military coup d’état in Myanmar, which energized pre-existing conflicts in the country and led to new unarmed and armed opposition movements against the junta. The military junta’s violent and indiscriminate response to the anti-coup opposition has come at a great human cost and has also led to the displacement of millions of Myanmar civilians both within and across the country’s borders to Thailand, India, and Malaysia. In the latter case, the new arrivals often join Myanmar diaspora communities of both migrant labourers and refugees fleeing previous waves of war and repression.

On 20 January 2025, nearly coinciding with the anniversary of the coup, dozens of civil society organisations supporting the Myanmar refugees on the Thai-Myanmar border were informed by USAID of an immediate suspension of critical aid. Some six weeks later, this suspension became a permanent termination. The USAID cuts are a major setback and are not the only aid reductions undercutting programmes critical to supporting Myanmar refugees abroad. Other donors have or are planning to reduce their overall aid budgets, including the UK Government. Moreover, the US has withdrawn funding from key humanitarian agencies, such as the World Food Program. Simultaneously, the political environment in countries hosting Myanmar refugees has become increasingly hostile to refugees, and hundreds of Myanmar citizens have been repatriated – which for many, both women and men, has meant an immediate forced conscription by the junta into its war against the opposition forces.

Prior to these developments, our team had conducted XCEPT-supported research in Thailand and in Mizoram State in northeastern India from March – May 2024, which focused on the different displacement experiences of Myanmar refugee women. Even before the complications brought on by aid cuts and increasingly hostile political environments in the host countries, almost all refugee women struggled to survive economically, had minimal access to services, feared deportation and forced conscription, and struggled to connect with Thai and Mizoram host communities due to language barriers and a lack of proper documentation. However, different women and gender diverse persons were exposed to these burdens, risks, and challenges differently. Unsurprisingly, the more access to social and financial capital one has, the more one is buffered from some of these risks and the more services one can access. Those with less (or without) capital, clout, and connections struggled more. Women heads of households and widows, who were often the sole providers for their families, struggled to cope with the financial burden, and often highlighted their fatigue and depletion in the interviews. This was even truer for women who had disabilities or chronic illnesses, and/or who had care responsibilities for family members with disabilities. For elderly women refugees, old age loneliness was an issue, especially in urban centres, where they lacked contacts to the host communities and their younger family members were busy at work.

Most of our interviewees strongly felt that the anti-junta uprising had indeed increased women’s political and social participation and, to a lesser degree, led to more openness on LGBTIQ+ rights. However, the struggle for economic survival and the double burdening of women, who were juggling with both domestic care responsibilities and paid labour, left little time for participation. Moreover, deeply entrenched heteronormativity and patriarchy, including amongst male leaders of the opposition, has kept decision-making power in the hands of (older) men.

The recent combined development of the aid cuts with the increasingly restrictive policies of host countries have created new pressures on a scale that the refugee communities have not faced before. The aid cuts will mean that refugees will have to rely even more on the informal support networks which they have established themselves instead. However, these informal support networks, as well as wider political participation for minority groups, will be harder to maintain as even more time will now go towards ensuring economic survival as a direct consequence of the aid cuts. Meanwhile, given increasing political hostility toward refugees in host countries, we anticipate that the refugees will attempt to make themselves less visible and less likely to advocate for assistance or participate in activism, due to fears of deportation and subsequently forced conscription.

Though we have no doubt that the women’s and LGBTIQ+ rights activists amongst the refugees will continue to work for a more equitable Myanmar, the preexisting struggles they face have become even more fraught due to the external forces coalescing around Myanmar refugees.

Chatham House’s XCEPT research explores transnational conflict across the Middle East, North Africa, and the Horn of Africa. By tracing the movement of people, goods, and capital across borders, the programme examines how conflict extends beyond national boundaries and what this means for effective policy and programming. In the below short videos, Chatham House researchers discuss their research projects for the XCEPT programme.

Tim Eaton, Senior Research Fellow, MENA programme, discusses the business of migrant smuggling in and through Libya, which has, since 2011, become the primary corridor for irregular migration to Europe from sub-Saharan Africa.

Read Tim’s paper, coauthored with Lubna Yousef, here. Other recent XCEPT-Chatham House research papers examining the political economies of migration from Africa to Europe include “Tracing the ‘continuum of violence’ between Nigeria and Libya” by Leah de Haan, Iro Aghedo, and Tim Eaton; and “Tackling the Niger–Libya migration route” by Peter Tinti.

The Iranian-led ‘axis of resistance’ suffered significant setbacks in 2024, amid conflict with Israel and other political turbulence, leading some observers to conclude that it has been seriously weakened or is even on the verge of defeat. However, the axis has historically proven highly resilient. Chatham House Senior Research Fellow Renad Mansour discusses how Iran and its networks adapt to external pressures.

Read “The shape-shifting ‘axis of resistance’”, by Renad Mansour, Hayder Al-Shakeri, and Haid Haid.

Local conflicts, such as those in Sudan and Ethiopia, have wider transnational impacts — showing how violence and competition over resources quickly spill across borders, shaping broader political and economic dynamics. Chatham House Africa Programme Senior Research Fellow Ahmed Soliman discusses the regional economic effects of these conflicts.

Read “Gold and the war in Sudan” by Ahmed Soliman and Suliman Baldo, and “The ‘conflict economy’ of sesame in Ethiopia and Sudan” by Ahmed Soliman and Abel Abate Demissie.

War leaves scars – physical and mental. Refugees fleeing conflict do not simply leave their experience of war behind them when they cross a border towards safety. For instance, even as the war in Syria drove millions of people from their homes and their country—making Syrians one of the largest refugee populations in the world, with Jordan hosting over 619,000 Syrian refugees within and outside camps in urban communities—their experiences of the war back home continue to shape their lives in Jordan, affecting their mental health, social trust, and ability to rebuild support networks.

Exposure to conflict before displacement continues to influence the social well-being of refugees many years later. We find that not only do refugees face substantial barriers to establishing stable lives and livelihoods, but that integration outcomes vary widely based on location, with those in urban settings facing different opportunities and challenges compared to those in refugee camps. In addition, the variation in refugees’ places of origin in Syria and their arrival dates in Jordan means they carry diverse pre-displacement experiences, which continue to shape their adaptation and social well-being in their new environment.

Social well-being is an important factor in evaluating whether an individual lives a fulfilling life. We include three key aspects:

These dimensions of social well-being influence not only a refugee’s ability to cope with hardship but also their prospects for integration and long-term stability.

We show that not all conflict experiences have the same impact on social well-being. Having been close to conflict events does not necessarily lead to long-term suffering. Instead, we find that the severity of the violent conflict—particularly exposure to fatalities—has profound and lasting effects. Refugees who experienced many fatalities in Syria report lower life satisfaction and have weaker social safety nets. The experience of past violent conflict events can continue to shape lives, even years later.

Mental health shapes how the experience of violent conflict shapes long-term social well-being. We find that depression is a key mechanism through which past trauma continues to affect refugees today. Those who were exposed to severe conflict are more likely to suffer from depressive symptoms, which in turn reduces their trust in others and weakens their social ties. Women, in particular, report higher levels of depressive symptoms when they had experienced intense conflict before displacement. Without proper mental health support, these emotional wounds persist, making it harder for refugees to rebuild their lives.

Refugees often face multiple challenges at once, creating what is known as a ‘polycrisis’. In our forthcoming study, we find that experiencing environmental stressors—such as drought—before displacement exacerbates the difficulties faced by displaced populations today. Syrian refugees who experienced both severe conflict and environmental hardship suffer even greater social isolation. These overlapping crises make it harder for refugees to establish stable support systems, further deepening their vulnerabilities.

Not all refugees experience displacement in the same way. Household structure plays a crucial role in shaping social well-being. Individuals in female-majority households suffer greater declines in life satisfaction after experiencing conflict, while individuals in male-majority households experience a steeper decline in social support networks. These findings suggest that gender dynamics influence how families cope with displacement and trauma.

Another important insight concerns the difference between refugees living in camps versus those living in host communities. We find that the lasting adverse legacies of conflict exposure on social well-being are concentrated among refugees in camps. This difference suggests that while camps may provide basic necessities for survival, they may also isolate refugees more from broader society.

Five key takeaways from our research can guide policies and programs to better support refugee communities:

The legacies of war do not end when refugees cross a border. Past trauma continues to shape the social well-being of refugees for years to come. By acknowledging these realities and implementing evidence-based policies, host countries and international organizations can better support refugees in rebuilding their lives. Understanding the long-term impacts of conflict is a crucial step toward creating programs and systems that support the most vulnerable and alleviate suffering around the world.

We thank the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) for data access and support.

Duncan Green used a great metaphor in his recent blog when he called the recent mega-cuts in global aid budgets a tsunami. We are witnessing the sudden transformation of the aid sector that is losing life and diversity at a dizzying rate, like a coral reef weakened by rising sea temperatures and then battered by a mighty wave. And the good is being swept away with the bad.

Over the past year I’ve been giving methodological backup to a local partner on the Somali-Kenya border to work in a new way with ten rural communities. We’ve been supporting all kinds of different people there to reflect on their reality through storytelling and action. It has brought us into contact not only with remarkable people in the borderland, but also with people working in the humanitarian sector in the two countries, from local NGOs, to contractors, to donors, to UN. Everyone I’ve spoken to in the last few weeks has been in some kind of shock about the changing system. Some still don’t quite believe it’s happening, as programmes close, budgets evaporate, and collaborations dissolve.

For many it’s a question of how to save core operations. But for some of us, especially those of my peers working in insecure and damaged places, it’s a question of how to get back to the basics of who humanitarianism is for and what it’s for. It’s these actors that I’m most interested to watch and support as they pivot to make good out of the meltdown.

On the ground on the Somalia-Kenya border the effects of the tsunami are more muted. There never was much effective aid to these ten villages, even though they have been battered by 30 years of civil war and 15 years of efforts to counter the growing al-Shabaab insurgency. Local people work with each other to navigate indiscriminate violence, going about their lives as pastoralists, shop owners, mothers, traders, educators and the like. They rely on tradition for order, as elders and religious leaders solve disputes and pronounce on customary law, but importantly they are also innovating in fertile social networks that bring new ways of thinking and acting in society.

We heard examples of local people managing water systems, hiring their own teachers, and running generators to provide electricity to whole settlements. We heard how young people get businesses going, women negotiate better treatment by authorities, and how traders and pastoralists move where they need to, largely unmolested by the armed actors. They are paying taxes to both insurgents and at government checkpoints, negotiating the sums down as low as they can, and arguing for armed actors to leave their villages and livestock camps out of the firing line.

Summing it up, one of the community members explained that their way of life is a ‘middle way’ along which they navigate their survival, negotiate how they are treated and innovate in a changing society.

What can we learn from all of this? It’s not about what they need and don’t need in the way of material aid. It’s about how things bloom or how they get stuck in communities, wherever they are. Local experience of aid has been that its logo emblazoned staff come, when they do appear at all, with announcements and interventions, or with workshops and new languages of how community should comport itself. They don’t ask how the community already blooms and where it gets stuck.

What could the middle way mean for us as we navigate the new normal? I think that the way these ten communities are managing local governance (away from government and aid agencies) gives us pointers as to how to work better in their support. It’s not a new idea, rather it’s one that for me started with Robert Chambers’ question ‘whose reality counts?’ Community reality is changing rapidly, and if we want to align with it, we need to understand it and engage with it.

Participatory activists and innovative philanthropists all over the world already know this. They already have a myriad of wonderful ways of aligning. Last year Niranjan Nampoothiri and I did a small project for Citizen University in Seattle. We had the luxury of spending quality time with seven amazing participatory activists in seven countries around the world, learning who they are and how they do things, and sharing that with participatory activists in the US. They showed us an elegant, simple and determined set of ways of working well for the common good.

Duncan Green suggests that people coming afresh to the aid sector in this tumultuous time should consider avoiding the most stressed agencies. He suggested that instead of approaching those who depend on massive funding and high overheads, they should offer their services to those resilient organisations that emphasise social enterprise, solidarity and innovation at low cost and to big effect.

If rather than using a deficit model based on filling southern needs with generous northern largesse, we rebuilt after the great aid tsunami using a surplus model by which groups, communities, and municipalities strengthen themselves (with a little help from their friends), I think the people of our ten small places on the Somalia-Kenya border might congratulate us for finally getting it right.

Since the ouster of the Assad regime in December 2024, the transitional authorities in Damascus have repeatedly vowed to sever Hezbollah’s reliance on Syria as a key smuggling corridor. For over a decade, it is reported that the group has freely moved drugs, money, and weapons through Syrian territory to finance and arm itself. In an effort to translate promises into action, the new authorities have ramped up security along the border with Lebanon, dismantled drug trafficking infrastructure, and intercepted arms shipments destined for Hezbollah.

While these measures have likely disrupted Hezbollah’s operations completely, eradicating smuggling remains an immense challenge. Hezbollah’s entrenched networks, the economic drivers of illicit trade, the transitional authorities’ limited security capacity, and the sheer scale of the porous border all make total elimination unlikely. Without a comprehensive, multi-pronged strategy, cross-border smuggling will persist in post-Assad Syria.

Disrupting Hezbollah networks

Given its longstanding alliance with the Assad regime and direct involvement in the Syrian conflict, Hezbollah has become a prime target for the country’s new leadership. Despite the group’s withdrawal following Assad’s fall, the transitional authorities have taken a firm stance against Hezbollah-linked smuggling. Since Assad’s defeat, they have reportedly intercepted 13 weapons shipments bound for Hezbollah and arrested individuals involved in arms smuggling. They have also seized large quantities of narcotics and shut down drug production facilities across central and southern Syria.

On 6 February 2025, the crackdown escalated with the launch of a large-scale security operation in Qusayr, a strategic Hezbollah stronghold near the porous Syrian–Lebanese border. The operation targeted over a dozen villages that had remained under Hezbollah’s control and are home to Lebanese Shia families with longstanding ties to the group.

Syria’s Ministry of Defence stated that the campaign aimed to sever key smuggling routes in this critical region, which, according to the Homs border security chief Major Nadim Madkhana, had served as ‘an economic lifeline for Hezbollah and traffickers of drugs and arms.’ In fierce battles lasting several days, security forces uncovered more than 15 drug production facilities, stockpiles of illicit materials, and a counterfeit currency printing press producing fake $100 bills.

Interwoven challenges

Despite the recent successes of the transitional authorities, Hezbollah-linked smuggling operations are unlikely to end soon. Several key factors ensure their persistence. The 330-kilometre Syrian–Lebanese border remains inherently difficult to monitor. Much of it is unmarked and winds through valleys and mountains – terrain long exploited by drug smugglers and arms traffickers.

Compounding this challenge, Hezbollah has spent over a decade entrenching its presence along the border, building an extensive network of covert paths and tunnels to facilitate illicit activities. This deeply rooted infrastructure makes it nearly impossible to eliminate smuggling routes through security operations alone. The group also maintains a firm grip on the Syrian side of the border, particularly in the Beqaa Valley.

Additionally, Hezbollah’s long-standing ties to local smuggling networks bolster its ability to sustain cross-border operations. These networks reportedly include whose members operate on both sides of the border and have deep affiliations with Hezbollah. Heavily armed and well-resourced, these families have been engaged in smuggling for generations and possess intimate knowledge of the terrain. By leveraging their expertise, resources, and adaptability, these local networks can quickly respond to security crackdowns, including by relocating to areas inside Lebanon when targeted by Syrian authorities and vice versa. In addition to identifying alternative routes when necessary, smugglers are strengthening their operations by employing more sophisticated evasion tactics, such as concealing illicit substances within legitimate goods.

Furthermore, Syria’s deepening economic crisis, widespread unemployment, skyrocketing living costs, and high demand for both legal and illicit smuggled goods make smuggling an increasingly essential lifeline for border communities.

The capacity problem

Syria’s fragile security situation and the limited capacity of its new authorities present significant challenges to achieving their stated objectives. Despite toppling the Assad regime in just 11 days, the new leadership – led by Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (HTS) – lacks the military and security infrastructure needed to effectively govern and secure the vast territories left in the regime’s wake. While efforts are underway to strengthen their capabilities, this process will take time.

Militarily, the HTS-led coalition remains fragmented. Although HTS, as Syria’s de facto ruling force, has persuaded most armed factions to merge under the Ministry of Defence, this unity is largely superficial. Many factions continue to operate under their original command structures, limiting overall cohesion and effectiveness.

Security forces are even more constrained. The new authorities primarily rely on HTS-linked General Security, an understaffed and overstretched force that functions more like an armed crisis response unit than a fully operational security apparatus. As a result, it lacks the resources to effectively monitor the border with Lebanon or combat the operations run by various networks, including Hezbollah’s.

The situation is similarly dire in Lebanon, where security forces also struggle with capacity issues. Their presence in Hezbollah strongholds – especially in the Beqaa Valley – is minimal to non-existent.

A broader strategy is needed

Syria’s new authorities have shown clear determination to disrupt Hezbollah’s illicit smuggling networks, particularly those involving weapons and drugs. As the transitional government builds capacity, Hezbollah’s cross-border operations will face increasing risks. However, eliminating the group’s ability to use Syria as a smuggling corridor will remain a formidable challenge – at least through military means alone.

A lasting solution requires a comprehensive strategy rooted in strong coordination between Syrian, Lebanese, and international actors. Beyond bolstering border security, efforts must address the root causes of smuggling by curbing demand for both illicit and legal contraband while investing in economic development programmes that offer viable alternatives to those who rely on smuggling for survival. Without these measures, Hezbollah’s entrenched networks will continue to exploit Syria’s vulnerabilities, deepening instability within the country and threatening broader regional security.

This article originally appeared on Kalam, the website of Chatham House’s Middle East and North Africa Programme.