On March 4, Jon Alterman spoke with Renad Mansour, senior research fellow and director of the Iraq Initiative at Chatham House, and Sanam Vakil, director of the Middle East and North Africa program at Chatham House, about the resilience of Iranian networks in the Middle East. Their discussion builds upon a recent Chatham House report Renad co-wrote on the topic. The following episode is a slightly condensed version of their conversation. You can find a link to the video of the complete discussion below.

“The war rages just across the border, while we endure sleepless nights in the refugee camps of Bangladesh,” recounts a 30-year-old Rohingya man, who hides in nearby villages to evade forced conscription by armed groups.

Myanmar’s civil war has crossed international borders. As we write this, Rakhine State in Myanmar, the ancestral homeland of the Rohingyas, is undergoing a seismic transformation. Since the collapse of a ceasefire in November 2023, Myanmar’s military junta and the Arakan Army (AA) have fought an intense war over the future of Rakhine State, within which the Rohingya were caught in the crossfire. The subsequent year of fighting has led to the death of more than 1,300 people, mass displacement, and a new territorial order. In 2024, AA made substantial territorial gains and now controls most of Rakhine state, including the entire border with Bangladesh. These dramatic shifts in power cast a long shadow over the already uncertain future of the Rohingya in Myanmar. The Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh’s camps have also been drawn into the escalating war – turning spaces of refuge into an extended battlefield. The renewed transnationalisation of conflict has changed the patterns of gendered violence in the camps, manifesting itself in new refugee movements, the proliferation of Rohingya armed groups, forced conscription campaigns and the imposition of a morality driven and culturally inscribed masculinity, and high prevalence of sexualised violence against women and girls.

Escalating violence has exposed the population in Rakhine to new threats from multiple sides. Extrajudicial killings, arson, rape, and other severe human rights violations against the Rohingya have been reported. A new wave of displacement followed as approximately 80,000 Rohingya sought refuge in Bangladesh in recent months. As of February 2025, the official figure of Rohingya living in the world’s largest refugee camp surpasses one million. These camps have only basic infrastructure, and the rights of the ‘Forcibly Displaced Myanmar Nationals’, which is the official label for the Rohingya in Bangladesh, are minimal. They lack livelihood options and are almost totally dependent on humanitarian aid.

The refugee camps in Bangladesh have become sites of violent power struggles among armed groups, most notably the Arakan Rohingya Salvation Army, Rohingya Solidarity Organisation, Arakan Rohingya Army, and Islami Mahas. These groups have created a climate of fear among refugees. They informally control the camps as ‘night governments’ and operate with near impunity both within the camps and in the wider Bangladesh-Myanmar borderland.

Since early 2024, the Myanmar military, desperate to maintain control, had resorted to forcibly recruiting Rohingya men and boys in Rakhine, exploiting their vulnerability and statelessness. The armed groups active in Bangladesh’s camps also started to abduct Rohingya refugees to fight in Rakhine state. According to reports, over 5,000 male Rohingya were violently or voluntarily conscripted, trained in weapon use, and then sold to warring parties in Myanmar or became part of units of Rohingya armed groups actively engaged in combat. The conscriptions reveal a complex relation between refugeehood, masculinity, and nation-state formation as the armed groups created and instrumentalised societal expectations towards Rohingya men, particularly youth, who should demonstrate a “militarised masculinity” to protect their race, religion, and motherland. In this wake, Rohingya men themselves become highly vulnerable to violence, while patriarchal norms were reaffirmed and the social fabric in the Rohingya camps was transformed.

A representative of a humanitarian NGO working in Cox’s Bazar explained another tactic used by groups forcibly conscripting Rohingya men: “If the brother or father or the husband doesn’t want to go to Myanmar and fight, the groups threaten those families, particularly the daughters or wives. Basically, if the men don’t join, the women will be abducted and raped.” Rohingya women face threats and sexual abuse as leverage against their male relatives, but they also play a critical role in resisting abductions, hiding young men during recruitment sweeps or assisting their escape. Nonetheless, due to forced conscriptions, the deaths of fighters, and men’s onward movements (such as perilous sea journeys to Indonesia or Malaysia) many households in the camps are female-led, which amplifies women’s already existing vulnerabilities to violence.

These dynamics reveal the significance of the camp-border-nexus. The new power of both the Rohingya armed groups in Bangladesh and the Arakan Army in Myanmar rests on their mobility and networks on both sides of the border. Cross-border trafficking of licit and illicit goods, including drugs, forced recruitment, human smuggling, and kidnapping for ransom have become part and parcel of the transnational war economies that continue to fuel violence in both countries.

There is a need for a radically different way of looking at the Rohingya humanitarian crisis, especially if we are to understand its transnational manifestations and gendered nature. To date, the Bangladeshi government and international partners have viewed gender-based violence against Rohingya as a local humanitarian problem that mainly concerns women. While it is true that women and girls are most vulnerable, and most GBV incidents take place in the camps, this focus on violence against women and the site of the camps is too narrow. As sketched, new patterns of gendered violence have emerged, in which Rohingya men are the main targets, and which are clearly linked to armed groups’ cross-border entanglements. Addressing this transnational landscape of gendered violence and enhancing the protection of both Rohingya women and men is a challenge. Nevertheless, recent changes in Bangladesh’s policy, the formation of a Rohingya Task Force, and the upcoming UN summit on the situation of the Rohingya led by Bangladesh’s interim government, offer a rare opportunity to reset the official and humanitarian strategies that have been in place for almost a decade. The chance must not be missed to then also address the transnational roots of insecurity and gendered violence in this contested borderland.

Local understandings of pollution

Unity State, situated in north-central South Sudan, is home to a significant proportion of the country’s oilfields. It is also subject to large-scale flooding. The ensuing flooding started in 2020.[1] Some communities, especially in the Southern part of the state, believed it started much early than this—around 2019.[2] Flooding water in Unity has been there with no significant sign of going away, and this only keeps increasing the level of the water already there each season.

The state’s rural population has been suffering the negative effects of pollution especially since the construction of a pipeline through Unity State in 1999 and the intensification of oil extraction following the Comprehensive Peace Agreement in 2005.

Prior to the post-2005 intensification in oil production, local Nuer regarded the effects of ‘pollution’ as being down to minor everyday actions such as eating with unwashed hands; touching faecal waste; coming into contact with the remains of a dog, donkey, cat or snake; or even just eating unfamiliar foods. However, in the wake of the extreme flooding seen in 2007, together with the rise of modernity—or chop wic as the Nuer would call it—the concept of pollution as it is locally understood has started to change.

Now, local people regularly claim the oil extraction and intense fighting seen in Unity State since the 1990s have poisoned the soil and water, causing sickness in both humans and animals. For instance, thousands of dead fish, mostly tilapia, have been spotted in flooding along the Bentiu–Unity road. It is believed that toxic chemicals from oil production and pollution have entered the drinking water of the communities and their cattle. While the cause of death is unclear, many believe the fish died due to oil pollution in the water. Also believed to be contaminating the water are the vast quantities of unexploded ordinance and military debris strewn along roads, around barracks or where battles took place. All of this is lueng—a Nuer word that literally translates as poisoning, but is also used to describe the general effects of pollution.

To date, little has been done by the state authorities to help mitigate the situation. Thus, when it comes to dealing with the problems posed by water pollution, people are heavily reliant on traditional methods, such as building dykes around their homesteads to prevent influxes of contaminated water.[3] Alternatively, villagers may choose to move away from the source of pollutants, such as the carcass of an animal killed by contaminants. This often involves migrating from flooded land to biil (raised land).[4] Continued, widespread flooding has, however, led to shrinking areas of biil, making it difficult for rural populations and their livestock to secure unflooded—and therefore unpolluted—land. This has led to local tensions and in some cases conflict.

The social impacts of pollution and flooding

A number of serious social problems have arisen in Unity State due to the recurrent flooding and increased pollution. Some reports found that there has been increased in number of children born with birth defects.[5]Here, is it worth noting that there has never been a time when the region’s rural residents have had adequate access to clean, treated water. Although humanitarian organizations did at one-point install hand pumps in some areas, these have now either been uprooted or swallowed by the floods, forcing entire villages to rely on potentially contaminated water. This situation has led to escalating complaints about diarrhoea and the fact that local clinics are unable to provide proper treatment.

Several conflicts have flared due to growing numbers of displaced people crowding into dwindling higher ground, with those thought to possess disease-bearing animals sometimes prevented from settling in these areas. Peter Machieng Chan Gatduel attributed poor agricultural productivity and disruption of civilian livelihoods to dramatic changes in climatic variations such as increased in rainfall and flooding.[6] At the same time, many families displaced from rural villages have either sought refuge in the homes of town-based relatives or sought out dry ground in and around towns, sometimes claiming these areas as their new homes. The area named Mia Sava, for example, is currently occupied by displaced villagers from Rubkona County.[7]Given the uncertainty created by the likelihood of further flooding, there are fears these incomers may decide to remain there permanently, potentially provoking inter-communal tensions.

Moreover, many young people have been separated from their relatives in the rush to migrate to safer areas, such as county headquarters or the state capital. Others, meanwhile, have been drawn into committing road robberies. Such anti-social behaviour is regarded by elders as stemming from dak rool lan (the ruin of our world). As a Nuer elder in Mayom County observes, ‘you can only control your children when you have the power to feed them’.[8]

Flooding and the spread of pollutants

There is still no clear understanding among rural Nuer about what is causing the extreme flooding—some attribute it the over-flowing of the Nile’s water, while others worry the gods have been angered. Nevertheless, 2007 marked a turning point in awareness about the impacts of pollution. The immense flood waters seen that year not only killed huge numbers of livestock and displaced many people from Mayom and Rubkona counties, but spread pollution from oil, war debris and dead animals across the landscape. Most people in the affected areas now believe pollution is affecting their livelihoods and health in ways that were previously unimaginable.

In 2021, Thep fishing camp—an area that runs along the border between Mayom and Rubkona—saw an outbreak of diarrhoea believed to have been caused by the consumption of contaminated fish. About 30 people were affected, ten of whom died. That same year, around 30 cows and 20 elephants were allegedly found dead near a pool close to Tharthiah oil field, with locals attributing their deaths to increased water and soil pollution.

Even more recently, a 2023 Sudd Institute report revealed communities are anxious that new forms of pollution may be responsible for the death of cattle, the deformation of newborn babies and the premature birth of infants.[9] Some residents complain their relatives or children have disappeared in the water, either because they drowned or were poisoned.

All this has led to a widespread local saying that the regular flooding is both a blessing and a curse: a blessing because it brings with it abundant water and fish; and a curse because it not only washes away their crops and top soil, but the contaminated water is perceived to bring unknown diseases that are infecting their cattle. Given the extreme level of flooding seen in recent years, many people now wish the waters did not come at all.

Nuer terms for forms of pollution

People are creating new names for pollution based on the symptoms they observe in a sick cow or person. For example, the flooding of 2014 and 2015 brought with it a serious cattle disease that the pastoralist community in Mayom County named Juornyin (eyes disappear in), based on the fact the cow’s eyes become watery and over time sink deep into its head. Thousands of livestock were lost to the disease, leaving many families with nothing. It is now prohibited to consume any cattle that has died of Juornyin, as residents believe their flesh has been polluted by as-yet-unknown substances. The pastoralist community is possibly the most affected by pollution issues, as their animals depend entirely on untreated water and vegetation.

A similar theory is evolving about local fish populations, with some residents asserting that the taste of tilapia and Nile perch has changed in recent years due to the effects of pollution. People are therefore becoming increasingly selective about which fish they buy at markets for home consumption. Many rural villagers now prefer mudfish and catfish, with these changing tastes reflected in the prices charged for the respective fish: in Mankien fish market, a mudfish sells for SSP 3,000 (about USD 0.60 during the research period) while the equivalent Nile perch sells for SSP 2,500 or less.[10]

Conclusion

Pollution caused by oil extraction and past conflict is, alongside repeated extreme flooding, causing significant negative impacts for the rural communities, livestock and aquatic life of Unity State. Despite repeatedly complaining of birth defects, residents living near oil wells have largely been ignored.

Meanwhile, most villagers are only too aware of the dangers of pollution, but lack the scientific tools necessary to obtain credible information on the local effects of contamination. Thus, until such time as the state is willing to take meaningful action, rural populations must seek their own solutions, such as moving to higher ground or avoiding potentially polluted food wherever possible. It is unlikely, however, that such measures will be viable over the long term.

Notes

[1] Edward Eremugo Kenyi, ‘Climate Change, Oil Pollution, and Birth Defects in South Sudan: A Growing Crisis’, South Sudan Medical Journal 17, no. 4 (December 3, 2024): 157–58. Accessed 15 February 2025, https://doi.org/10.4314/ssmj.v17i4.1.

[2] Focus group discussion (FGD) with farmers and firewood/water-lily roots collectors in St. Bakhita Parish, Mayom, 2 June 2024. FGD with elders and farmers, Mankien, 3 June 2024.

[3] KII with RRC County Director, Guit County, Bentiu town, 15 May 2024.

[4] KII with an NRC Protection worker, Bentiu town, 15 May 2024.

[5] Kenyi, ‘Climate Change, Oil Pollution, and Birth Defects in South Sudan’.

[6] Peter Machieng Chan Gaduel, ‘Reviewing the Climate-Security Nexus: The Impacts of Climate Vulnerability on Pastoralist Conflicts in the Unity State Region, South Sudan’, Queen Mary University of London Global Policy Institute, 2022.

[7] FGD with displaced people, Biemruor, Bentiu town, 21 May 2024.

[8] KII with Paramount chief in Mankien Payam, 6 June 2024; KII with an ex-combatant, Rubkona town, 18 May 2024.

[9] Nhial Tiitmamer and Kwai Malak Kwai Kut, ‘Sitting on a Time Bomb: Oil Pollution Impacts on Human Health in Melut County, South Sudan’, Special Report, The Sudd Institute, January 2021.

[10] FGD with fishermen, Bentiu, Bilnyang/Gany River, 22 May 2024.

Since the 2011 war in Libya, migrant smuggling and trafficking through the country has flourished. This interactive explainer from Chatham House looks at three phases in the development of the migrant smuggling trade through Libya.

In 2011, a brutal conflict between Sudanese government troops and Sudan People’s Liberation Movement–North (SPLM/N) fighters in the Nuba Mountains region forced civilians caught up in the violence to flee across the border to South Sudan.[1] There, in Yida—the first of three refugee camps to be established in the area—the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) saw to the basic needs of those who had been displaced, including their food, shelter, health and education. Refugees were also able to cultivate crops using handmade farming tools, with the fertile land in Yida camp providing consistently good harvests.

Previously, children living in the Nuba Mountains were often involved in unpaid household work such as bricklaying, cattle-grazing and farm work. Having been displaced, however, the comprehensive international support provided—which extended to unaccompanied children separated from their parents—meant this practical assistance was no longer needed.

In 2020, the long proposed resettlement of refugees living in Yida camp brought an end to UNHCR support. As a consequence, many children in Yida—and increasingly the other two camps as well—have had to seek paid work in order to supplement their family income. Such employment, which can often take children beyond the confines of the camp, includes building work, assisting Bagara nomads with cattle-grazing, and selling poles, grass or charcoals. In undertaking such tasks, children are frequently exposed to financial exploitation and dangerous conditions, placing them at risk of physical and emotional harm. Moreover, the dire economic situation faced in the camp has led to rising numbers of girls and young women having to submit to forced and/or early marriage.

Given the current Sudan war has led to a new wave of displaced people seeking refuge in South Sudan, there is a very real possibility that these dynamics will be further exacerbated over the coming months unless appropriate action is taken. This blog is based on XCEPT research in 2024 involving extensive interviews with Nuba Mountains refugees on South Sudan’s border to understand these dynamics.

Yida, Ajuong Thok and Pamir camps were established in South Sudan’s Ruweng administrative area in order to host refugees escaping the Nuba Mountains conflict.[2] Yida camp served as the main entry point from South Kordofan, and initially hosted 20,000 refugees—mostly survivors of the Kadugli massacre in June. Shortly afterwards, in November 2011, the Sudanese air force provoked international outrage by dropping two bombs on Yida camp, killing 12 refugees and injuring 20. By 2013, the camp’s population had increased to 71,000, the vast majority of whom were women and children.

In March 2013, UNHCR and South Sudan’s Commission for Refugees Affairs established Ajoung Thok camp, which initially held 24,000 refugees and currently hosts over 55,000 refugees.[3] The last of the three camps to be set up was Pamir in September 2016, which was intended to host refugees relocated from Yida camp. Having started out with 34,000 refugees, the camp is currently home to more than 50,000 people, its population swelled by new arrivals escaping the ongoing war in Sudan.[4]

In 2016, UNHCR and the South Sudanese government announced that, given chronic overcrowding issues, the security implications of the camp’s location 20 km from the border with Sudan, and the fact Yida had never been officially recognized as a refugee camp, its inhabitants were to be relocated elsewhere. The Nuba refugees rejected relocation to Ajuong Thok and Pamir, however, arguing the two camps were too close to the border area controlled by the Sudanese government, and that at least Yida was close to SPLM-N authorities in the Nuba Mountains.

Despite these objections, the formal relocation process was eventually set in motion: in October 2019, UNHCR discontinued its food assistance in Yida, and two months later Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) stopped its medical services. By 2020, refugee schools had been left in the hands of the South Sudan state government, with water and sanitation handed over to local authorities and the refugee community.

During the course of 2020, just 2,758 Yida refugees were relocated to Pamir. Although children could continue to access free education in Pamir, the food ration there was halved from four to two malwas (gallons) of sorghum per person per month, further discouraging Yida refugees from resettling. The relocation has since led to a number of negative impacts for the refugees remaining at Yida, while those living in the two newer camps are also facing increasing hardship. Access to water has become more difficult, while clinical drugs are harder to find, forcing many to turn to herbal medicine.

Of particular concern when it comes to children is the loss of access to free education. Government school fees were initially set at USD 1 and USD 2 per term respectively for primary and secondary schools (based on three terms per school year). These fees have since increased to USD 3 and USD 5 respectively. Many parents, who are already struggling to provide enough food for their families, simply cannot afford these rates.

As a consequence, many children are now having to take up paid work or are leaving home to seek a better life, whether inside the camp or further afield, in Parieng, Liri, Rubkona or the Nuba Mountains.

In the past, children living in the Nuba Mountains region would often be expected to participate in domestic tasks as a means of passing on necessary skills for later in life.[5] For instance, children with pastoralist parents would likely be involved in camel, goat, sheep, cow or donkey rearing, while the children of farmers might be given small plots of land to tend. Other household duties assigned to children included hunting, fishing and collecting wild fruits or firewood. Despite these responsibilities, children (those aged 5–17 years) still had sufficient time to play with their friends.

More recently, having a formal education has acquired greater importance, with most parents keen to ensure their children go to school. When the 2011 war erupted, many Nuba people migrated to South Sudan partly to ensure their children could continue to access a school education.

Today, however, children from poorer families are having to work not to acquire skills, but simply to earn money. One avenue of employment is bricklaying. This would previously have been viewed as man’s work, but the pressures wrought by displacement, the war in Sudan and inflation in South Sudan mean women and children now have to engage in this often back-breaking work for meagre wages.

Another way in which children can make money is assisting Bagara nomads. In this scenario, the refugee parents agree to let the nomad take their child away for the purposes of helping graze their animals, sometimes for months on end. The child is paid a he-goat (worth about USD 100) for every month they work. The he-goats are usually then sold by the parents in order to buy sorghum to supplement the family’s diet, or purchase shoes, medication and soap for other siblings. Having to spend months away from home inevitably means the children assisting the Bagara nomads must forego their education.

According to UNHCR refugee law, refugees are not supposed to return to their countries of origin or even leave the camp to travel to other parts of the host country. The growing difficulty of meeting daily needs has, however, driven many refugees to move to Liri (in Sudan) in search of farming jobs. Commercial farm owners in Liri offer reasonable wages, equivalent to about USD 5 per day. In this scenario, children mostly cross over to Liri with adults, siblings or friends who have previously worked there. Older children (aged 12–17) are sometimes given accommodation by the commercial farm owners for the duration of their employment, following which they return to their camp and give the money they have earned to their parents. Alternatively, children may work alongside their parents before crossing back together.

Refugees arriving in Yida camp between 2011 and 2019 were provided with accommodation by UNHCR. Since then, however, refugees have had to build shelters themselves. In light of this, refugees—children included—have taken to collecting poles and grass from the nearby forest, which they then sell. Some are also involved in building structures for host community members, receiving the equivalent of USD 20 for each one they build. Other refugees have sought to make money by collecting firewood and making charcoal.

Again, tasks such were previously the preserve of adults, and only conducted by children for training purposes under the supervision of their parents. Now, financial imperatives mean it is commonplace for children, even younger ones, to take on these physically arduous tasks for money.

As already touched upon, there are a number of negative implications to children in refugee camps undertaking paid work. Most obviously, they will have less time and energy to attend school or complete homework.[6] Thus, in attempting to meet short-term needs, they end up compromising their long-term futures, perpetuating the cycle of poverty endured by their families.

Children forced to spend long hours engaged in strenuous work also risk suffering serious physical and mental health issues.[7] Mental disorders such as depression and anxiety have become commonplace among children in Ajuong Thok, Pamir and Yida camps, often—according to a focus group discussion with youths[8]—induced by injuries sustained through paid work and the lack of appropriate medication they receive afterwards.

In addition, many of the children who reside at their workplace end up sleeping without a mosquito net, rendering them susceptible to malaria and other chronic diseases.

Back when they used to live in the Nuba Mountains, children were almost entirely exempt from paid work. Now, the pressures of war, ongoing displacement, inflation, insufficient harvests and a lack of support from both the South Sudan government and international organizations mean refugee children—particularly those in Yida—must prioritize making money over pursuing an education.

If this state of affairs is to be reversed, then the government and NGOs must intervene to provide fully funded educational support to refugee children, especially those in direst financial need. In doing so, concerted efforts must be made to incentivize schooling over paid work.

[1] Sudan Human Security Baseline Assessment (HSBA). www.smallarmssurvey.org/project/human-security-baseline-assessment-hsba-sudan-and-south-sudan.

[2] UNHCR, ‘South Sudan: Yida refugee settlement profile’, 28 February 2020. Accessed 23 January 2025, https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/74632.

[3] UNHCR, ‘South Sudan: Ajuong Thok refugee camp profile’, 28 February 2020. Accessed 23 January 2025, https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/74627.

[4] UNHCR, ‘South Sudan: Pamir refugee camp profile’, 28 February 2020. Accessed 23 January 2025, https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/74631.

[5] L. Aquila, ‘Child Labour, Education and Commodification in South Sudan’, Rift Valley Institute, 2022. https://riftvalley.net/publication/child-labour-education-and-commodification-south-sudan/.

[6] Olivier Thévenon and Eric Edmonds, ‘Child labour: causes, consequences and policies to tackle it’, OECD working paper, November 2019.

[7] Anaclaudia Fassa et al., ‘Child Labor and Health: Problems and Perspectives’, International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 6: 1 (2000), 55-62.

[8] FGD with Rawada, Fatuma, Alamin, Idriss, Samarn, Naina and Jalla, Yida, 12 June 2024.

In 2014, the self-styled Islamic State committed genocide against the Yezidi population in Iraq. To mark the anniversary of the genocide, Kings’ College London’s War Studies podcast featured Dr Inna Rudolf speaking with renowned Yezidi human rights advocate Mirza Dinnayi about what life is like for the Yezidi community ten years on from the genocide. Inna and Mirza discuss justice and accountability, the geopolitical situation in the Yezidis’ ancestral homeland, and what still needs to be done to support the community as they deal with a legacy of discrimination that precedes the atrocities of 2014.

This episode is available on Spotify, SoundCloud, and Apple Podcasts,

Kheder Khaddour is a nonresident scholar at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut. His research centers on civil military relations and local identities in the Levant, with a focus on Syria. Armenak Tokmajyan is also a nonresident scholar at the Middle East Center, focusing on borders and conflict, Syrian refugees, and state-society relations in Syria. Together, they recently published a paper, titled “Borders Without a Nation: Syria, Outside Powers, and Open-Ended Instability,” which was the culmination of several years of work on Syria’s borderlands, with the collaboration of Mohanad Hage Ali, Harith Hasan, and Maha Yahya. Diwan interviewed the two in late September to discuss the impact of Syria’s borders on the country’s conflict and its future.

Michael Young: You have just published a paper at Carnegie titled “Borders Without a Nation: Syria, Outside Powers, and Open-Ended Instability.” What do you argue in the paper, and what are your major conclusions?

Kheder Khaddour and Armenak Tokmajyan: We argue that after more than a decade of war, Syria’s international borders have not only remained intact but have also become more pronounced and reinforced, even as the national framework within those borders has collapsed. If you think about it, much of the Syria we knew before 2011 no longer exists. Many concepts and terms have lost their meaning, or their meaning has changed. One exception is borders, which have become increasingly emphasized and

demarcated, though to varying degrees depending on the specific border. This is largely due to the centrality of borderlands in the evolution of Syria’s conflict, as well as the role played by regional actors who seem to have utilized these international borders as barriers, with the aim of containing Syria’s problems within its territory.

At the same time, despite the endurance of sovereign borders, no new national framework has emerged. While the intensity of war and violence has subsided since 2020, the conflict itself remains unresolved. The containment of Syria’s multilayered grievances within more solid borders may help regional actors to mitigate spillovers, but it won’t resolve the underlying issues in the country. This, in turn, heightens the risk of partial implosions or the collapse of authority from within. We’ve already seen early signs of this across Syria, such as in Suwayda, where the regime’s authority and legitimacy were challenged to an unprecedented degree last year (even more than during the war years), and in Idlib, where Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, which once appeared firmly in control after a period of stability, faced serious internal fractures.

MY: Your focus on borders underlines that you feel that control over border areas will be an essential feature in defining Syria’s future. Can you unpack this idea for readers?

KK and AT: To understand the evolution of Syria’s armed conflict, one cannot overlook the significance of the country’s borderlands. Numerous actors and factors have come and gone, influencing the trajectory of the conflict, yet the central role of border areas has remained constant—and has even grown in importance. In 2011–2012, rebellion and revolution spread across Syria, but dissent was particularly strong and sustained in its border regions. After the tide turned in2016, the Syrian regime, with the support of its allies, succeeded in pushing many threats toward border areas, but failed to decisively end the civil war by force. Diplomacy also failed to midwife an understanding between Damascus and rebellious border peripheries. As a result, the conflict today remains heavily concentrated in Syria’s borderlands. Any future resolution will not have to deal with international borders, since they are intact, but will have to reimagine the borderlands and their relationships with the much-weakened political center in Damascus.

MY: You point out that demographics, cross-border economic relations, and security have been main drivers of the dynamics in Syria’s border areas. Can you explain what you mean, and what the consequence of this have been?

KK and AT: With the collapse of the national framework, new local-regional links emerged, reshaping security, economic, and demographic dynamics, especially in Syria’s borderlands. This is particularly evident in the northwest, where Turkey’s presence and influence have brought about profound changes on all three levels. However, similar patterns can be observed not only in areas where the regime’s control is absent or contested—such as the northeast and Daraa in the south—but also in border areas with Lebanon and Iraq, where the regime, alongside its allies (notably Hezbollah and pro-Iranian militias), maintains control. While these areas are considered to be under the regime’s authority and do not directly challenge Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s rule, strong local-regional ties, particularly with Iran, have been developed there, often at the expense of Syria’s sovereignty.

MY: Among the many outside actors in Syria, who do you think is the most consequential, or influential, in the country’s border regions, and why?

KK and AT: Not all foreign actors have the same influence or resources in Syria. However, major change by any one of the actors—notably the United States, Russia, Turkey, or Iran—could be very consequential. These regional and international actors, along with their local allies, are in a delicate equilibrium. Any pronounced shift from one of the key actors could lead to a collapse in the equilibrium among all of them. This prevents any side from making significant advances without disrupting the balance of power, which could allow others to expand their influence. In theory, this situation could shift if any one of the major actors were to significantly alter its policies. However, currently there are no strong indicators this will happen. Yet should it occur, it would certainly create a power vacuum in Syria, potentially triggering a cascade of conflicts until a new status quo is established.

MY: What is the way out of the present impasse? You write that a path to restoring national authority must take place in an “inter-Syrian process” that rests on a “consensus among main regional powers that Syria must remain united, that no one side can be victorious, and that perennial instability threatens the region.” What do you mean by such a process, and is a regional consensus possible given the contenting interests of regional powers in Syria?

KK and AT: This is a delicate question with no clear or easy answer. The way we see it, the primary obstacle to change in Syria is the regime in Damascus. The regime, quite openly, has no interest in discussing a new national framework. It claims to already have one and expects others to forget the war and adopt its vision, which is built on pillars such as personalized rule, autocracy, centralized governance, and economic monopolies—in other words, “Suriya al-Assad,” or “Assad’s Syria.” This approach, and the regime’s central role in the Syrian equation, makes it impossible to begin the search for a new national framework.

Another key point in our analysis is that Bashar al-Assad, and even the broader regime itself, cannot last indefinitely. Despite the regime’s resilience, the road ahead will be challenging, especially if there are internal collapses or a major shift in the balance of power, as discussed earlier. To be sure, these changes could either benefit or weaken the regime. But the key point is that even if Assad manages to navigate these challenges, he is 60 years old and is not immortal. That moment could present an opportunity for a new national framework to emerge, necessarily with active involvement from regional actors. This turning point could potentially shift Syria from its current state of stalemate and crises, both internal and external, toward some form of stability.

Syria remains in a state of civil war, or a form of it. The country’s path to stability will only come through regional and international powers, but the success of this evolution is tied to an inter-Syrian process to create a vision reuniting the Syrian people in a new national framework. This prospect is difficult to imagine in the coming years, but it is also the only means to achieve stability.

This article was originally published by The Conversation on 15 October 2024.

The assassination of Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, in September sent shock waves through the Middle East and beyond. Nasrallah had evolved into the very embodiment of Hezbollah over his 32 years in charge, and had established himself as a key figure in Iran’s so-called axis of resistance.

At the height of his influence, Nasrallah was so widely admired from North Africa to Iran that shops sold DVDs of his speeches, cars were embellished with his image, and many Lebanese even used his quotes as ringtones.

He is not the first sectarian leader to have been assassinated in Lebanon. And on each occasion the killings have intensified sectarian tensions in the country and have jeopardised social stability. The impact of Nasrallah’s death will, in my opinion, probably be no different.

His killing could destabilise the fragile balance of power in the country. And it could also trigger a reshuffling of political alliances within Lebanon’s complex sectarian power-sharing framework that was established in 1990 after the end of the civil war.

A man in Baghdad, Iraq, carries an image of the late Hezbollah leader, Hassan Nasrallah. Ahmed Jalil / EPA

In 1977, the leftist leader of the Druze community, Kamal Jumblatt, was assassinated by two unidentified gunmen in his stronghold in the Shouf mountains of central Lebanon. Many of his followers believed they knew who was responsible, and channelled their anger toward Lebanon’s Christian community.

Security officials reported that more than 250 Christians were killed in revenge, many brutally, with their throats cut by Druze assailants. At least 7,000 Christians fled their villages after the killings, with around 700 of them travelling to the presidential palace in Baabda, a suburb of Beirut, to request government protection.

This spell of fighting marked a significant escalation of sectarian violence during the civil war, and resulted in a persistent cycle of retaliation, deepening division and entrenched sectarian identities.

Then, in June 1982, a powerful bomb explosion killed Lebanon’s Maronite Christian president, Bashir Gemayel. The assassination was carried out by two members of the Syrian Social Nationalist party, reportedly under orders from Syria’s then president, Hafez al-Assad.

The next day, Israeli troops entered west Beirut in support of the Phalange, a Lebanese Christian militia that blamed the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) for Gemayel’s death. Israel had earlier that month launched a massive invasion of Lebanon to destroy the PLO, which had been carrying out attacks on Israel from southern Lebanon.

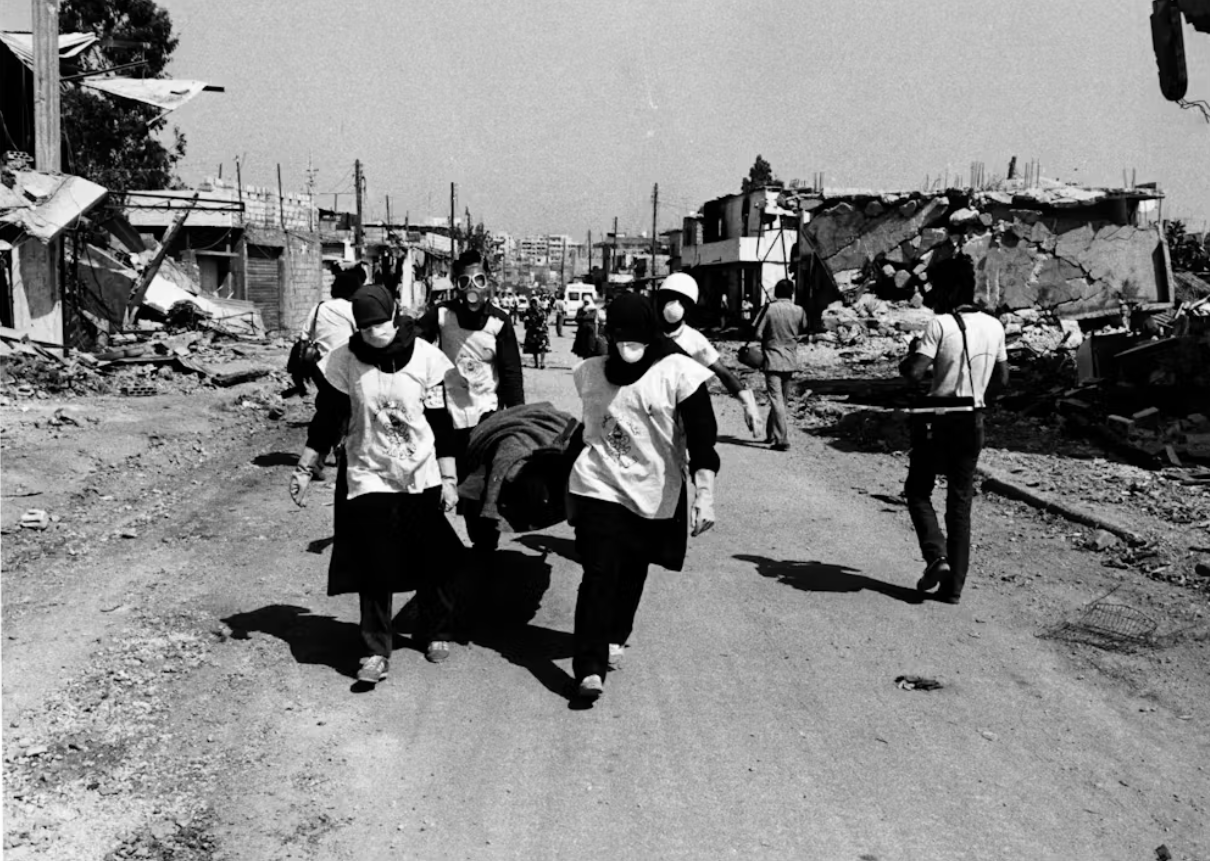

Knowing that the Phalangists sought revenge for Gemayel’s death, Israeli forces allowed them to enter the Shatila refugee camp and the adjacent Sabra neighbourhood in Beirut and carry out a massacre a few months later. Lebanese Christian militiamen, in coordination with the Israeli army, killed between 2,000 and 3,500 Palestinian refugees and Muslim Lebanese civilians in just two days.

Scores of witness and survivor accounts say women were routinely raped, and some victims were buried alive or shot in front of their families. Women and children were crammed into trucks and taken to unknown destinations. These people were never seen again.

UN relief workers at the Shatila refugee camp in the aftermath of the massacre. Keystone Press / Alamy Stock Photo

Following the end of Lebanon’s civil war, there was a period of relative stability as a delicate balance of power was established between Lebanese sects. But a car bomb in downtown Beirut in 2005 killed the country’s former prime minister, Rafic Hariri, and again altered the dynamics of sectarian rivalry in Lebanon.

Lebanon lost one of its central figures, while fury over Syria’s alleged involvement in Hariri’s murder raised international pressure on Syria to end its 29-year occupation. The withdrawal diminished Syria’s influence as the primary mediator in the country, and the underlying tension between the two main sectarian groups vying for power, the Sunnis and Shia, surfaced abruptly.

Lebanon experienced 18 months of political deadlock and protests, with Hezbollah and its allies pushing for a veto power in the government. Hostilities intensified and violence became a constant threat.

Then, in May 2008, the Lebanese government attempted to remove a Hezbollah-aligned security officer and investigate the organisation’s private communications network. This ignited fierce clashes between supporters of the government and the Hezbollah-led opposition.

Hezbollah and its allies occupied west Beirut and at least 71 people, including 14 civilians, were killed over the following fortnight.

Hezbollah steadily expanded and enhanced its military capabilities over the next ten years. And it also emerged as a powerful regional player by joining Iran and Russia in supporting Bashar al-Assad’s regime in the Syrian civil war.

The organisation assumed an increasingly central role in Lebanese politics, and secured a majority of seats in the 2018 parliamentary elections.

Lebanon’s modern history is rife with conflict. The assassination of Nasrallah marks the latest in a series of bloody milestones that have served as sharp turning points – and even transformational moments – in Lebanon’s sectarian politics.

Christian and Sunni factions in Lebanon have for years viewed Hezbollah as effectively commandeering the state, leveraging its powerful military wing and Iranian backing. With Hezbollah now visibly weakened in the absence of its powerful and charismatic leader, this longstanding power dynamic may be set for a shift.

There are signs that divisions are already deepening. Videos from Tripoli, a predominantly Sunni city in northern Lebanon, show residents dancing in the streets in celebration of Nasrallah’s death. Other videos show people removing Hezbollah stickers from the vehicles of displaced Shias.

Meanwhile, Hezbollah supporters have pledged retaliation for Nasrallah’s elimination. Lebanon once again finds itself on the verge of fierce sectarian tension and instability.

This article was produced with support from the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research programme, funded by UK International Development. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

Despite an end to the active conflict in the Tigray region, Ethiopia’s political and security crisis is deepening. Much of the country’s insecurity is linked to competition over natural resources, which has fuelled land disputes and intensified cross-border smuggling, driven inter-communal conflict, and aggravated environmental hazards.

Ethiopia has substantial gold reserves, particularly in the areas bordering Sudan. These reserves made up more than 95 per cent of the country’s $428 million in mineral exports between 2023–24. Ethiopia officially exported a high of 12 metric tonnes of gold between 2011–12, a figure that fell to 4.2 tonnes in 2023–24, despite the emergence of new gold projects and the expansion of artisanal, or small-scale, mining.

Gold mining is increasingly informal and outside of federal government control. Several large-scale gold projects have been ‘in the pipeline’ for over a decade without starting official production. Some have been overtaken by illegal exploration, extraction and smuggling operations, often in collusion with various government and non-government actors.

Gold mining in Ethiopia is increasingly informal and outside of federal government control.

Confidential reports suggest that some foreign investors and Ethiopian geologists possess more detailed mining data than the government. Artisanal mining employs at least 1.5 million people (74 per cent of miners) and accounts for 65 per cent of mining foreign exchange earnings.

Of Ethiopia’s regions, Tigray leads the way in exploration and commercial licensing, with over 90 licensed gold mining companies. Tigray was among the biggest suppliers of gold to the National Bank of Ethiopia before the war, with about 26 quintals (2.6 metric tonnes) of gold annually, valued at around $100 million. Since the Tigray war, much of the region’s gold has instead been smuggled – with estimates that nationally, this amounts to as much as 6 tonnes of gold annually, significantly more than current official exports.

Multiple non-state actors, including leaders of the Tigray Defense Forces (TDF), foreign nationals, and local businesspeople are involved. Control over gold has been one of the reasons impacting the recent internal split within the leadership of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the dominant party in the region.

Reports suggest that TDF leaders and some members of the TPLF oversee most of the illicit mining, with gold smuggled out of Ethiopia through Sudan, to the UAE. This plunder of gold ultimately harms the Tigrayan public, as the resource should be used to rebuild the region destroyed by a devastating war. Equally worrying, the gold rush in Tigray is becoming increasingly violent. A recent conflict in a Rahwa gold mine in northwestern Tigray resulted in over 20 deaths.

Other conflict-prone regions are also seeing an expansion of the illicit gold sector, with Benishangul and Oromia regions ‘officially’ barely producing a quarter of the amounts projected by the government. A Canadian company agreed to invest $500m over 15 years in exploiting gold reserves around the small town of Kurmuk in Benishangul, along the Sudanese border. But encroachment by illicit miners has prevented access to the site, and the involvement of regional officials and local militants has left the federal government unable to act. There are reports of massive extraction taking place, with gold again being smuggled out via Sudan to the UAE.

Keen to prevent the loss of hundreds of millions of dollars every year, the Ethiopian government is trying to curb illegal mining. Cracking down on the illicit market, incentivizing legal suppliers, and amending restrictive and ambiguous laws are measures the government is taking.

However, contested authority between federal, regional and local administrations has paved the way for opportunistic, nepotistic, and criminal elements to profit, which fuels armed conflict. As such, the federal government’s ability to impose peace and security is uncertain at best.

These state and non-state elites also cooperate and compete for power in transnational spaces. Sudan is the primary recipient of illicit gold from Ethiopia due to its proximity to Ethiopia’s gold belt. Illicit gold from Benishangul, Gambela, Oromia, Tigray and parts of southern Ethiopia flows into Sudan via a porous border with the help of smugglers and brokers, facilitated by conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region and in Sudan.

The illicit gold networks in Sudan have flourished in its war economy. Profits generated by the smuggling of gold sustain the war efforts of armed actors.

Other smuggling routes traverse Afar to Eritrea and Somaliland, and the Guji area near the Kenyan border. Regional airports have also become transit points for illicit gold, which is sent to destinations like Uganda and then re-exported to the UAE.

The illicit gold networks in Sudan have flourished in its war economy. Profits generated by the smuggling of gold from and through Ethiopia, Eritrea, Uganda and as far as the DRC, alongside domestic Sudanese production, sustain the war efforts of armed actors, notably the Sudanese Armed Forces and Rapid Support Forces.

But it is the UAE that is the ultimate destination for much of Africa’s smuggled gold, including Ethiopia’s. According to a recent report by Swiss Aid, 2,569 metric tonnes of undeclared gold from Africa, worth a staggering $115 billion, ended up there between 2012 and 2022. The UAE’s questionable import procedures, which do not necessarily require detailed information about the origins of gold, as well as incentives to import ‘scrap’ gold, make it ideal for smugglers.

The expansion of illicit gold mining is exacerbating Ethiopia’s complex conflicts. Regional states have reclaimed mining concessions to assert control amid diminishing federal influence. At the same time non-state armed actors are competing for gold revenues to expand their local authority and, in some cases, challenge the authority of the state. The gold sector is becoming increasingly fragmented and militarized, and risks being drawn into multiple local and ethnic fractures as the federal government struggles to impose the rule of law.

But in addition to tackling issues at the national level, addressing this issue in the long term requires a better understanding of the transnational nature of gold flows across the region, and how these interconnections form part of a conflict ecosystem that operates across borders.

The UAE is both the prime customer for Ethiopia’s stolen resources and one of its most valued diplomatic partners, offering external support that is as valuable as gold to a government under enormous pressure. The UAE’s emergence as both patron and consumer of conflict gold is a contradiction that Ethiopian policymakers and international partners who support sustainable peace in the region will need to resolve if progress is to be made.

This article was produced with support from the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research programme, funded by UK International Development. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.