COP30 was initially celebrated for the unprecedented effort to promote Indigenous participation. Yet this effort quickly rang hollow, as only a small handful of Indigenous delegates were granted access to the conference’s Blue Zone, where actual negotiations and high-level decisions took place. The resulting resentment and criticism were hardly surprising, given that Indigenous lands are among the first to bear the brunt of deforestation, resource degradation, and broader extractivist pressures. While Indigenous voices were formally sidelined from decision-making in the COP process, the summit was marked by numerous Indigenous-led protests that made visible a different reality: Several indigenous communities are actively building their own spaces of environmental mobilisation rather than waiting for recognition.

In the Chile-Argentina-Bolivia tri-border region, indigenous peoples have developed cross-border, self-organised initiatives to defend collective rights to land, territory, and resource management in the face of escalating lithium extraction. These communities are not passive victims of the green transition, but key political actors whose struggles expose the contradictions at the heart of global climate governance.

Mining and Indigenous communities in the Lithium Triangle

Lithium is a mineral essential for energy transition because it is the primary component in batteries that power electric vehicles and store energy from renewable sources. Characterised by the presence of lithium-rich salares (salt flats), the area of the Andes mountains that spans the borders of Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile is known as the Lithium Triangle. It holds approximately 58% of the world’s lithium resources.

Exploration and mining in the Lithium Triangle occur on lands inhabited for thousands of years by Indigenous communities, including the Aymara, Atacama, Colla, and Quechua. Mining projects are generally governed by national and provincial authorities, with laws regulating resource extraction, environmental impact assessments, and land rights. However, these legal frameworks often overlook and violate Indigenous rights, particularly the principles of free, prior, and informed consent.

Mining activities also have harmful environmental impacts on the surrounding ecosystem, depleting water sources and contaminating the land, as well as harmful socio-economic impacts, compromising traditional livelihood activities and encouraging forced evictions.

Tensions within communities are also emerging between those that oppose mining and its long-term consequences, such as desertification, and those that welcome mining for its immediate material benefits, such as job opportunities. Nonetheless, tensions within communities have not yet escalated into open conflict. They are being carefully managed and contained by community leaders determined to preserve harmony and coexistence.

By contrast, tensions between communities and government authorities have frequently escalated into violence and open confrontation. This occurs when the communities’ anti-mining protests are met with disproportionate police force, including the use of rubber bullets, tear gas, and other crowd-control weapons. In several cases, anti-mining protesters have been arbitrarily detained or criminalized through dubious legal charges (such as accusations of ‘terrorism’, ‘sabotage’, or ‘obstruction of public services’) designed to delegitimise their demands, suppress activism, and instill fear.

Cross-border patterns of cooperation

Facing persistent tensions with their own governments and systematic exclusion from international decision-making spaces, Indigenous communities across the border regions of the Lithium Triangle have been coming together to defend their collective rights to land and resources and to oppose the expansion of lithium mining.

Among those cooperative initiatives, the Latin American Water Summits for the Peoples stand out. Begun in 2018 in Argentina’s Catamarca province, its goal is to reunite local communities and Indigenous peoples whose water sources are affected by lithium mining and who resist extractivism. The most relevant Summits – co-organised by Indigenous peoples themselves and held in Indigenous territories – were convened in September 2024 in El Moreno, Argentina, and in October 2025 in San Pedro de Atacama, Chile. When I visited Jujuy, Argentina, in October 2025, I sat with an Indigenous leader who was preparing to travel to Chile. The seriousness and passion with which he talked about the upcoming event clearly communicated the importance that locals attach to these cross-border inter-community forums.

The Water Summits involve debates and presentations by regional communities that are directly affected by lithium mining, as well as by people with scientific, legal, and academic expertise who are supporting the communities in their struggle. Activities such as the mapping of socio-environmental conflicts are carried out during those events to spread knowledge and awareness across communities on the specific realities that each of them is facing. Training sessions are also devoted to strengthening the capacities of communities to protect their water sources from the effects of lithium mining.

Plenary discussions are then used to advance common strategies aimed at continuing and sustaining cross-border anti-mining cooperation. In both 2024 and 2025, the Water Summits culminated into a final declaration in which the various communities collectively reiterated their determination to defend the Pachamama (Mother Earth in Quechua), reaffirmed their rights to their territories and resources, and denounced the current patterns of extractivism led by foreign companies who pretend to act under the banner of the green energy transition.

In the same spirit of the Water Summits, in January 2025 Jujuy also hosted the first Andean Intercultural Summit of Communities Affected by Lithium Exploitation, a meeting of more than 200 Indigenous representatives from Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, and Peru who convened to reject lithium mining in their ancestral territories. During the Andean Summit, community representatives expressed unanimous rejection of the serious environmental, social, and cultural impacts caused by lithium mining. They also signed a powerful declaration that called for free, prior, and informed consent of all Indigenous people prior to the initiation of extractivist projects and reaffirmed the unity of Andean peoples against mining: ‘We identify as a single Andean people, without any division established by borders… . We share the same problems caused by mining and racism, and we will take joint action to protect our Mother Earth.’

However, it should be noted that the impact of these nascent and expanding initiatives of cross-border cooperation has so far been largely limited to amplifying Indigenous voices against lithium mining and encouraging greater awareness – both within the region and internationally – of the social and environmental costs of the green energy transition. By contrast, their ability to generate tangible political change remains comparatively modest, constrained by structural power imbalances, weak institutional channels for Indigenous participation, and the dominance of state and corporate interests in resource governance.

Conclusion

In the Andes, we are witnessing unique and unparalleled forms of Indigenous cross-border cooperation that demonstrate the resilience, agency, and transnational solidarity of Indigenous peoples in the face of systematic exclusion from international decision-making spaces and conflictive responses by local governments.

The Water Summits and the Andean Intercultural Summit reveal the power of self-organised, cross-border cooperation through which communities share knowledge, strengthen their advocacy capacities, and collectively defend their territories against harmful extractivism. These initiatives matter because they articulate approaches to resource governance that are inclusive, community-centered, and culturally grounded – offering valuable lessons and models. They also matter in that they show how Indigenous communities are building alternative channels and practices for environmental action that transcend national borders.

Recognising and integrating these Indigenous-led networks into formal policy frameworks – through advisory roles, strengthened consultation mechanisms, and the application of free, prior, and informed consent – could help ensure that resource governance aligns with both ecological sustainability and social justice. In this sense, grassroots practices in the Andes not only challenge the limited engagement of Indigenous voices at forums like COP30 and the persistent repression of Indigenous demands within their own countries but also point toward more equitable and effective models for managing natural resources within and across borders.

This views expressed in this article are those of the author.

In April 2025, the leader of the White Army Youth in Akobo, South Sudan, met with the region’s diaspora community via the online Lou Nuer Community Forum. The White Army members were given money to buy food for their families, and, in return, they agreed to keep out of the conflict taking place in Nasir and to maintain peace in Akobo. South Sudan’s diaspora population, which is estimated to be 1.2 million, plays a significant role in influencing developments at home. Between 2014 and 2022, the diaspora contributed $5.7 billion USD in the form of remittances.[i] These funds are often utilised to fulfil basic needs and support development, but they also provide an important source of finance to armed groups.[ii] Alongside this, the diaspora community uses its significant influence to shape the ways in which its home communities respond to, or view, political and ethnic issues.[iii]

In the Greater Akobo region of Jonglei state, an area marked by persistent conflict and marginalised by the central government – due both to its inaccessibility and its assumed support of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army–In Opposition (SPLM/A–IO) – understanding the way in which the diaspora influence conflict dynamics is crucial to ensure effective peacebuilding efforts. While many diaspora communities contribute positively through remittances, education sponsorships, and peace advocacy, others unintentionally or deliberately sustain cycles of violence through the support of kinship-based retaliation, cattle raiding, and politically charged rhetoric.[1] Clarifying this dual role can help inform efforts to strategically engage the diaspora and redirect their energies towards projects that promote reconciliation and help local communities build resilience against violence.

Who are Greater Akobo’s diaspora communities?

The diaspora communities from Greater Akobo are largely comprised of individuals from the counties of Akobo, Nyirol, and Uror, who fled South Sudan during the country’s civil wars or who left in search of safer living conditions and better economic opportunities. Many found asylum in the Global North, particularly in Australia, the United States, Canada, and Europe, and have established semi-formal kinship-based associations abroad. These often mirror the social organisation and politics back home and are frequently organised around ethnic identities.

The diaspora communities from Greater Akobo are largely comprised of individuals from the counties of Akobo, Nyirol, and Uror, who fled South Sudan during the country’s civil wars or who left in search of safer living conditions and better economic opportunities. Some found asylum in the Global North, particularly in Australia, the United States, Canada, and Europe, while others moved to different cities in South Sudan, notably to Juba. Many of these diaspora communities have since established semi-formal kinship-based associations, which often mirror the social organisation and politics back home and are frequently organised around ethnic identities.

Kinship-based mobilisation and resource transfers

Greater Akobo’s diaspora organisations take an active role in responding to incidents of conflict or communal grievances from afar. As they often view conflict through a lens of ethnic solidarity, however, this means that their assistance can take the form of support for retaliatory raids, often justified as self-defence, rather than initiatives for reconciliation. For example, diaspora members have provided support and mobile airtime to coordinate cattle raids and to transport the injured during conflict. In periods of heightened tensions, diaspora actors have also been known to fund armed youth groups under the guise of ‘community defence’.

While some diaspora groups are structured with formal leadership, collecting contributions and funding operations in response to particular incidents, others operate informally, transferring money to individuals or small groups for specific retaliatory actions. Members of the diaspora also act outside of the group setting, with individuals contributing money to buy bullets and airtime. In some cases, outspoken members of the diaspora emerge only when crises erupt, advocating for violence and offering rapid mobilisation support.

In most instances, the actions taken by the diaspora are intended to protect their families or communities, but the outcome is frequently the same: escalated violence, abduction of children and women, widespread trauma, and a deepening cycle of revenge.[v]

The problem of distance and diverging priorities

One of the fundamental issues with diaspora involvement is the gap in lived experiences between those abroad and those on the ground. Despite their ability to remain in communication with their home communities, through the use of social media and satellite services, diaspora actors are often far removed from daily insecurities. At the same time, they may have different priorities, including political recognition or ethnic dominance. Meanwhile, communities in Greater Akobo face urgent needs, such as food, water, health, and security.

This difference in situation can increase feelings of resentment and distrust towards the diaspora community, with some questioning their patriotism and motivations.[vi] Nevertheless, the reality of daily life in Greater Akobo means that the diaspora can use the resources at their disposal to influence actions. When faced with a lack of alternative livelihoods, young people often listen to the voices of those who can offer them material incentives.

The influence wielded by the diaspora has negatively affected peace efforts on the ground, especially in areas where state presence is minimal or absent. Locally driven efforts to promote dialogue and peace education are sometimes contradicted by diaspora narratives on social media that encourage revenge or ethnic exceptionalism. In one example, a South Sudanese resident in Canada presented himself as the spokesman for the Lou Nuer White Army and posted press releases online ‘which in effect urged South Sudanese in Jonglei to go on killing each other’.[vii] The South Sudan Peacebuilding Opportunities Fund similarly reported that the diaspora’s influence in Jonglei was largely negative and undermined local engagement with their peacebuilding work.[viii]

The positive influence of the diaspora

Greater Akobo’s diaspora community undoubtedly contributes to the cyclic violence in the region, but members of the community also work to support peace, maintaining relationships with local peace activists, religious leaders, and teachers in order to encourage unity. Many of the churches, which promote messages of peace within and between communities, were established by those who had lived in the diaspora. These churches serve as vital links between the diaspora and local communities, and their founders maintain this connection by visiting the congregations on a yearly basis.

One resident of Akobo County, when talking about the installation of internet in the youth centre, also remarked on how contact with family in the diaspora can actually build peace: ‘When you decide to [harm] the other clan, you can communicate with people far away through a video call with people in the outside world, especially if you have relatives in America, or even Kenya and Uganda. They can tell you: “You guys, this is not how life should be.”’[ix]

Similarly, just as remittances contribute towards instances of armed conflict, the diaspora also dedicates fundraising efforts to helping the welfare of their communities. From December 2024 to January 2025, the Lou Nuer diaspora community raised $6,000 USD for a local initiative to support Akobo Hospital’s operational costs. In April 2025, Australia’s Lou Nuer community also raised money through their local church to help youth who were undergoing treatment after fighting in Nasir. Most Nuer students who attend schools in East Africa and Ethiopia are able to do so largely thanks to the financial support of relatives in the diaspora. Alongside this, those living in refugee camps receive assistance from diaspora members to help fill critical gaps created by insufficient food supplies.

A double-edged sword

The role of the diaspora in the conflict in Greater Akobo is a double-edged sword. While the promotion of revenge narratives and remittances can sustain violence, the community also holds largely untapped potential for supporting peacebuilding and building resilience against violence. In order to ensure the diaspora’s energies contribute to positive outcomes, their influence should be strategically engaged, rather than ignored or condemned.

One example of successful strategic engagement can be seen in Jonglei State, where the Twic East community has established a forum to unite its local and diaspora associations under a common purpose: to ensure the groups work together to achieve shared goals and to ensure that these goals actually meet the needs of the Twic East community in Jonglei.

In the forum, the leaders of diaspora associations across the world meet with the leaders of local community groups to coordinate support. The Twic East community in Juba then takes charge of disseminating and implementing this support amongst the community in Jonglei. This joint initiative has built stronger ties between the community and diaspora members, and has shown success in achieving shared goals, such as funding and building flood defence systems and providing educational scholarships to young girls.

By recognising the influence and importance of diaspora voices, and steering them towards positive outcomes, the people of Greater Akobo may have a chance to break free from cycles of violence. The challenge is immense, but so is the opportunity.

[1] This blog post is based on the author’s own fieldwork and observations.

[i] African Development Bank Group. (2024, 31 July). Country Focus Report 2024 – South Sudan. Driving South Sudan’s Transformation: The Reform of the Global Financial Architecture. African Development Bank Group. Accessed at: https://vcda.afdb.org/en/system/files/report/south_sudan_2024.pdf

[ii] Carver, F., Deng, S. A., Kindersley, N., Kirr, G., Lorins, R. & Maher, 2. (2018). South Sudan Diaspora Impacts. Rift Valley Institute. Accessed at https://riftvalley.net/projects/sudan-and-south-sudan/south-sudan-diaspora-impacts/

[iii] Kiir Amoui, G., & Carver, F. (2022). Perceptions about Dual Citizenship and Diaspora Participation in Political, Economic, and Social Life in South Sudan. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies Vol. 22 (1); Voller, Y. (2020). Advantages and Challenges to Diaspora Transnational Civil Society Activism in the Homeland: Examples from Iraqi Kurdistan, Somaliland and South Sudan. Conflict Research Programme, LSE, p. 25.

[iv] Meraki Labs. (2021). Conflict Dynamics Driving Displacement in Akobo. Danish Refugee Council.

[v] POF South Sudan. (2025,17 March). Forging a sustainable path: Jonglei-GPAA Strategy Dialogue for a shared 2030 vision. Peacebuilding Opportunities Fund South Sudan. Accessed at: https://www.pofss.org/blog/forging-a-sustainable-path-jonglei-gpaa-strategy-dialogue

[vi] Kiir Amoui, G., & Carver, F. (2022). Perceptions about Dual Citizenship and Diaspora Participation in Political, Economic, and Social Life in South Sudan. Diaspora: A Journal of Transnational Studies Vol. 22 (1).

[vii] Johnson, D., H. (2014). South Sudan’s Experience at Peacemaking: The 22nd Annual Gandhi Peace Festival. In Bertrand Russell Peace Lecture: Symposium on Conflict and Peacemaking in South Sudan. Ontario, Canada: McMaster University.

[viii] Vincent, D. N., & Comerford, M. (2021, July). Lessons Learned #5 Practising peacebuilding in South Sudan. Peacebuilding Opportunities Fund South Sudan.

[ix] Trimble, J. (2022, 14 January). Building peace through connectivity. Norwegian Refugee Council. Accessed at: https://www.nrc.no/shorthand/stories/building-peace-through-connectivity/index.html

While walking through the streets of Hamra, Beirut, in autumn this year, I came across an advertisement for a restaurant. The poster promised that customers would be able to ‘taste the Golden Age of Beirut.’ A few metres later, another advertisement appeared: this time it was for an event inviting participants to ‘relive the Golden Era of the ‘50s, ‘60s and ‘70s Lebanon.’

Such references are not unusual. Beirut’s streets are saturated with nostalgic evocations of its once-prosperous past. In May 2025, ahead of the municipal elections, Downtown Beirut was littered with billboards bearing political messages. Against an image of 1950s Martyrs’ Square, an electoral coalition under the name of ‘Beirut Loves You’ promised its constituencies that ‘the glory days will return.’ Another billboard from the same campaign floated the identical line over a photo of a bustling Place de L’Etoile, this time taken in the early 2000s during the city centre’s post-war reconstruction – a project which itself drew heavily on nostalgia for Lebanon’s ‘Golden Age’. The campaign’s message was clear: Lebanon’s so-called glory days of the 1950s and 1960s can be recaptured, resuscitated, and projected onto the Lebanon of today. Within this interplay between memory and imagining, nostalgia becomes more than mere sentiment – it becomes a political tool.

Nostalgia is a complex emotion that describes a desire to recapture or revive aspects of the past, shaping the way people imagine their future. Although not inherently political, nostalgia has been progressively politicised, fuelling the rise of ethnic nationalism and the populist radical right in Europe and the United States, as it offers a ‘return’ to a secure, idealised past in the face of uncertainty and perceived threats from an increasingly globalised world.[i] In Lebanon, people may look back at the ‘Golden Age’ as a time of (relative) stability and prosperity – but allowing oneself to be continually swayed by this romanticised version of the past weakens the ability to respond to the demands of the present and the challenges of the future.

Lebanon’s ‘Golden Age’: prosperity for the few?

Lebanon’s ‘Golden Age’ refers to the 1950s and 1960s, when the country underwent rapid economic and infrastructural development.[i] With its flourishing banking sector and booming tourism industry, Beirut emerged as a regional cosmopolitan hub, and it was during this era that Lebanon gained prominence as the ‘Switzerland of the Middle East’ and its capital the ‘Paris of the Orient.’ These labels were further cemented after the 1956 Bank Secrecy Law that attracted foreign capital and transformed Beirut into a financial haven.

Yet, while banks’ profits soared, the wealth they generated failed to translate into broader social development. An economy increasingly dependent on finance, commerce, and luxury services left little space for industrialisation or agricultural reform. As a result, despite its cosmopolitan façade, Beirut came to embody stark socioeconomic inequality, its prosperity flourishing at the expense of its peripheries, deepening the rural-urban divide. A select few – traders, bankers, and members of the oligarchic elite – accumulated immense wealth, while many others were left behind.[ii]

Unsurprisingly, the frustrations and grievances caused by this inequality erupted into protest. In 1958, while the country was split over Lebanon’s pro-Western foreign policy, citizens took to the streets to demonstrate their growing resentment at the uneven development. The protests exposed the fragility and injustice of the elite-dominated economic model, and these tensions continued to escalate right up to the eve of the Lebanese civil war in 1975, when they exploded again.[iii]

Utilising nostalgia after the civil war

Despite the fact that socioeconomic inequality was one of the factors that contributed to the outbreak of civil war, decision-makers drew heavily on nostalgia for Lebanon’s ‘Golden Age’ to shape the post-war reconstruction of Beirut. When Rafic Hariri became Prime Minister in 1992, his vision of transforming Beirut into the ‘Singapore of the Middle East’ reflected a desire to restore the city’s pre-war regional and international standing.[iv] Beirut’s Central District, once known for its cosmopolitan ‘Souk’ or ‘Bourj,’ became an exclusive retail centre hosting high-end brands that only a small segment of Lebanese society could afford. This space, which had previously welcomed people from all walks of life for business and social exchange, was transformed into an exclusive area which favoured the wealthy. The reconstruction may have aimed to revive the commercial spirit of the ‘glory days’, but it ultimately did so at the expense of reconciliation, further deepening divisions in the capital.

Alongside the physical reconstruction of Beirut, decision-makers also turned to the 1950s and 1960s to guide Lebanon’s post-war economic rehabilitation. In practice, this meant re-financialising Beirut through investments in luxury real estate, the banking sector, and transnational financial flows managed by the Central Bank. Other sectors, such as agriculture, manufacturing and public infrastructure, were pushed to the margins. This system, which again promoted the interests of a narrow elite over those of the rest of the population – and was characterised by a culture of corruption and impunity – ultimately led to the country’s economic collapse in 2019.

Lebanon following the financial crisis: Continuity, not reform

Today, six years after the 2019 financial crisis, Lebanon has once again failed to implement meaningful structural reforms to its economic model. Negotiations with the International Monetary Fund (IMF) over potential aid and loans, which began in 2022 but were postponed several times, have yet to yield any results. While the IMF continues to push for reforms, Lebanon’s political elites and the banking sector remain unwilling to accept any agreement that might threaten their interests.[i]

Instead of confronting the flaws of a system that has repeatedly revealed its fragility, Lebanon’s ruling class has doubled down, further entrenching an economic model designed to self-destruct. In this light, calls for a return to the ‘Golden Age’ reflect more than a shared longing among decision-makers to recapture the prosperity of the 1950s and 1960s. They signal a determination to preserve the old order: one that safeguarded the affluence and privilege of the few at the expense of the many.

Why looking back won’t save Lebanon

In Lebanon, the so-called ‘Golden Age’ continues to cast a long nostalgic shadow. It appears in familial stories passed down by grandparents recalling the economic boom of the 1950s and 1960s, and in taxi drivers’ tales of foreign tourists who once crowded the Hotel District, skiing in the snow-capped mountains by morning and swimming in the Mediterranean by afternoon. But beneath this seemingly harmless recollection lies something more threatening: a romanticisation of inequality, impunity, and injustice.

While idealised visions of the pre-war era may offer comfort to parts of the population in times of crisis, they also distract leaders from addressing present-day priorities. After the civil war, rather than pursuing meaningful state-building, decision-makers resurrected the economic model of the ‘Golden Age’ wholesale, without reckoning with its flaws or critically heeding the lessons of both 1958 and 1975.

This pattern persists today as Lebanon seeks to re-financialise its capital following the 2019 financial meltdown and the most recent war with Israel. Instead of delivering long-overdue reforms demanded by the international community, Beirut held a so-called ‘investor conference’ in November 2025, in an attempt to reinvigorate the Lebanese economy. Participants included Arab investment funds and prominent global firms, including BlackRock, Morgan Stanley, and General Atlantic.[i] Lebanon once again turned to the economic model of the ‘Golden Age’ to rebuild its capital in the wake of crisis and conflict.

It is important to push back against the prevailing nostalgia for Lebanon’s so-called ‘glory days’ and instead expose the systems of violence and impunity that were already taking root at the time. It is only through a critical reflection of the past (both pre-war and post-war) that we can challenge the state’s capture by an entrenched ruling class and ultimately pursue an equitable reform agenda that holds the political, banking, and business elite accountable, without further burdening the Lebanese citizens, who have already borne the heaviest costs of the crisis.

Maria El Sammak is a Research Assistant on the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research programme. She holds an MA in Conflict, Security and Development from King’s College London, and she previously worked with the Berghof Foundation in Beirut, focusing on peacebuilding and conflict transformation. Maria’s research explores questions of memory, violent conflict, and post-conflict dynamics in Lebanon.

[i] “Economic Minister and Head of the Economic and Social Council Launch the ‘Beirut One’ Conference,” L’Orient Today, October 21, 2025. https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1482041/economy-minister-and-head-of-the-economic-and-social-council-launch-the-beirut-one-conference.html

[i] Philippe Hage Boutros, “Lebanon’s Unified Front for the IMF Falls Apart in Washington, ”L’Orient Today, October 20, 2025, https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1481884/lebanons-unified-front-for-the-imf-falls-apart-in-washington.html

[i] Sara Fregonese. “Between a Refuge and a Battleground: Beirut’s Discrepant Cosmopolitanisms.” Geographical Review 102, no. 3 (2012): 316–36. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1931-0846.2012.00154.x.

[ii] Fawwaz Traboulsi. A History of Modern Lebanon. 2nd Edition. London: Pluto Press, 2012. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt183p4f5.

[iii] Cobban, Helena. The Making Of Modern Lebanon. 1st ed. United Kingdom: Routledge, 2019. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429312465; Trabousli, A History of Modern Lebanon, 2012, 165-166.

[iv] Guilain Denoeux and Robert Springborg. “Hariri’s Lebanon: Singapore of the Middle East or Sanaa of the Levant?” Middle East Policy 6, no. 2 (1998): 158-73. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-4967.1998.tb00317.x.[i] Gabrielle Elgenius and Jens Rydgren. “Nationalism and the Politics of Nostalgia.” Sociological Forum (Randolph, N.J.) 37, no. S1 (2022): 1230–43. https://doi.org/10.1111/socf.12836.

In this episode, Professor Roddy Brett, Professor of Peace and Conflict Studies and Director of the Global Insecurities Centre at the University of Bristol, joins Dr Nafees Hamid, Co-PI of the XCEPT research programme, to discuss his new book, ‘Victim-Centred Peacemaking: Colombia’s Santos-FARC-EP Peace Process’.

Professor Brett reveals how the victims’ delegations changed the dynamics of the Santos-FARC-EP peace process, transforming victim-perpetrator relations and ultimately shaping the final agreement, which was signed in 2016. At a time when the number of civilian casualties in armed conflict is rising around the world, the Santos-FARC example offers valuable insights into how to effectively involve victims in peacemaking.

In the last twenty years, a rapid succession of crises—floods, droughts, rebellions, and national wars in Sudan and South Sudan—have been capitalised on by commercial investors working with both state-allied and private security partners. These corporate interests have built a cheap and mobile waged labor force through layers of rents, taxes, fees and debts. This growing cash labor market securitises oilfields, farms, mines, businesses and compounds that stretch along the disputed national border between Sudan and South Sudan. In the center of this long border lies the oilfield state of Unity in South Sudan, which borders the Nuba Mountains in Sudan. Both regions now fall under a patchwork of armed authorities’ zones of control. These authorities remain relatively fixed despite the spreading frontiers of the war in Sudan since 2023 and the fragmentation of the South Sudan state, because they are rooted in military-commercial empires built since the wars of the 1990s.

To understand the dynamics of this military-commercial economy and the class stratification and labor relationships it generates, Marko and Manal spent a month travelling across this landscape in sustained conversations with its workers. This short intervention makes three arguments. First, we should understand pollution and (increasingly regular) climate disasters as part of the coercive arsenal of governing authorities in post-statist neoliberal borderlands like this one. Second, these authorities are interested in creating “labor traps” within their toxic geographies to capture cheap or free productive and social-reproductive labor (following Spiegel et al. 2023; Scott and Rye 2025). Third, creating this captive depressed market strengthens opportunities for the regional and international extraction of corporate profit.

Environmental coercion

In the last six years, climate change-related flooding events and extractive pollution have accelerated on the borderland between Sudan and South Sudan. Massive flooding has become an annual disaster, especially in the Rubkona area and across refugee camps in Ruweng in 2021, and across the whole region in 2022. The borders and Nuba mountains suffered a deeply destructive drought in 2023 followed almost immediately by massive flooding across the whole region as well as widespread locust destruction in the mountains; 2024 brought another year of widespread flooding. Repeated oil pipeline disruptions have created localized pumping and storage crises. This oil pollution, as well as cyanide waste from gold mining in the Nuba Mountains, has been carried further afield by increasingly wide flooding.

Public authorities use the region’s repeated environmental disasters as a tool in local government—in mobilizing communities against each other—and in economic control, driving people into refugee camps, towns and commercial farms for safety and job-seeking. This is a common logic of regional war tactics: like the Sudan Government’s bombardment of the Nuba Mountains from 2013, the South Sudan Government’s wars in Unity State in 2014-2017 and 2019-2022 aimed at destroying the socio-economic base of perceived opposition areas through the wholesale destruction of farms and herds. Climate change-induced floodings (controlled in part by decisions over where dykes and levees are built) are a cheaper method of population control than full military operations, but achieve the same ends: impoverishing perceived opposition strongholds and creating new displaced settlements of desperate workers.

Labor traps

War, floods, droughts, pollution and inflation are all economically productive for governing authorities because they create useful immobility, trapping people into urbanization, encampment, and market dependency. Governing authorities and their commercial partners have benefited from the urbanization of a large number of desperate people seeking rented homes and any work going. The region’s international and internal borders are not technically “closed,” but fees and taxes levied by a plethora of military and civil authorities at checkpoints are both immediate local authority revenues and create high costs of movement, making better-paid migrant work options north and south too expensive to access, especially for women.

This labor entrapment has provided significant opportunities for regional investors to build an extractive commercial economy based on rent monopolies and cheap labor costs. Members of the military-political classes running government and army systems in this region—many since the 1990s—have invested in long-term warehousing and domestic rental units, commercial agricultural and extractives projects, private transport and security companies. On the other hand, repeated losses from conflict and environmental disasters have undermined middle-class and working-class abilities to reconstruct and re-invest. This has generated the possibility of monopolies alongside rapid vertical class stratification, where a much smaller class of wealthy entrepreneurs compete to consolidate corporate and administrative controls that allow them to invest, selectively tax, suppress wages, and control population movements (see also Pattenden 2024 and Martiniello 2019, both on Uganda). This has created a market for very low-paid piecework and self-employed market supply work, including providing transport and food services. Human labor is now cheaper than renting transport: in the 2023 dry season, some Mayom traders hired women to carry goods to Rubkona, over at least 80 kilometres, instead of renting a truck.

Extraction and corporate profit

Ordinary workers are fully aware of these dynamics of class construction and exploitation. In our research, we gathered songs—written predominantly by women, including by famous female songwriters—that explicitly set out the analysis we presented above. Esteemed songwriter Elizabeth Nyaduiy Bidiet articulated the sense of broken vertical relationships and the abrogation of wealthy responsibilities in crises in a recent song: “the daughter of Mr. Mading doesn’t bother with us, because people greet only those with big buttocks [Neer ke ni ram mi te ke wuoth: only those with big buttocks are greeted or respected]. Then I ask: where will those with no buttocks go to?”

These conditions are dangerous for people to live and work in, with few rights and little recourse. This captive market, which continues to provide opportunities for enclosure and rent extraction, provides its monopoly capitalists with high returns at low cost. Securitisation of these zones of profit—the oilfields, farms, mines, markets, compounds, and transport systems that stretch across the borderland—is made cheap through the instrumentalization of climate change patterns and securitised corridors of (im)mobility.

This article originally appeared in American Ethnologist.

Martiniello, Giuliano. 2019. “Social Conflict and Agrarian Change in Uganda’s Countryside.” Journal of Agrarian Change 19 (3): 550–68. .

Pattenden, Jonathan. 2024. “Exploitation, Patriarchy and Petty Commodity Production: Class, Gender and Neocolonialism in Rural Eastern Uganda.” Review of African Political Economy 51 (May): 16–41.

Scott, Sam, and Johan Fredrik Rye. 2025. “The Mobility–Immobility Dynamic and the ‘Fixing’ of Migrants’ Labour Power.” Critical Sociology 51 (1): 71–86.

Spiegel, Samuel J., Lameck Kachena, and Juliet Gudhlanga. 2023. “Climate Disasters, Altered Migration and Pandemic Shocks: (Im)Mobilities and Interrelated Struggles in a Border Region.” Mobilities 18 (2): 328–47.

Our research assistants were Linda Madeng Gatduel, Nyaphean Phan Char, Bisal Hassan, Razaz Juma and Gisma Yousif.

As a researcher, you often read about conflict from a distance. You hear stories, collect data, and listen to people recount their experiences, usually after the worst of the violence has passed. Conflict becomes something abstract, something you analyse. Most researchers don’t plan to be in the middle of it while conducting fieldwork.

Moyale is a town of around 34,000 people, located atop an escarpment that rises abruptly amidst the low rocky hills and brushland that characterise the area. The Kenyan-Ethiopian border runs through the town, with one of Kenya’s and Ethiopia’s major border crossings located in the centre of the town, along a key highway that also serves as Moyale’s main thoroughfare.

One morning in early March 2024, during my field research, my field coordinator and I were preparing to visit a nearby village to meet with a local women’s group. The plan was to spend the day hearing from women about their experiences, their roles in the community, and their aspirations for peace in an area that hasn’t always experienced it. But the day took a sharp turn.

We received word that the meeting would have to be cancelled. Violent clashes at a number of gold mines had broken out in Dabel, a region in Marsabit County, Kenya (of which Moyale is the largest town) and several victims were being brought to Moyale for medical treatment. Moyale’s previously calm atmosphere shifted instantly. My field coordinator, a member of the Gabbra community, started receiving urgent phone calls. Tensions were rising rapidly between the Gabbra and the Borana, the two dominant communities in Marsabit.

Uncertain of how events would unfold, we stayed put. In situations like these, the safest course of action is to follow the guidance of local partners who know the terrain, the networks, and the dynamics better than anyone. One of the first people we contacted was Rahma, a local peacebuilder and a respected leader in her community.

She was composed but serious. She immediately updated us on what was happening: the violence in Dabel had triggered a ripple of anxiety in Moyale, and tensions were threatening to spill across the border into Ethiopia, as they had previously. “No one wants Moyale to burn again,” she said, referring to violent clashes in 2012 between the Boranna and Garri communities. That violence, which began as a dispute over land use and grazing rights, killed 18, displaced around 20,000 from Ethiopia into Kenya, and garnered international attention.

When I asked how her local peacebuilding organisation group were responding, Rahma spoke with quiet determination. The first step, she explained, was to alert the elders from both communities. “When the elders speak, people listen,” she said. Her team had already reached out to them, urging them to call for calm and prevent any escalation. Simultaneously, they were supporting those injured in the clashes who had been brought into town, ensuring they had access to basic care and support.

But Rahma’s work didn’t stop there. She had begun visiting families of the victims, offering solidarity, helping them process what was happening, and quietly gathering information. She and her team were also sending alerts to women on the Ethiopian side of Moyale, warning them of potential escalation. This early warning system, built on personal relationships, is often the difference between violence being contained or spreading further.

In those tense hours, I witnessed first-hand an often opaque and unacknowledged process of local, women-led peacebuilding. It was happening in real time: the phone calls, the home visits, the coordination between elders, youth, and women’s groups. The effort to prevent the spread of violence wasn’t being led by armed actors or official peace envoys; it was being led by women like Rahma, who, in the absence of formal authority, exert extraordinary influence through relational leadership, local knowledge, and moral authority.

This experience reshaped how I understand peacebuilding. It is not a grand event or a signed document; it is often the quiet work done by those with the most to lose. It is those without official standing, often women, who issue early warnings, who offer first response, who try to ease tensions, and try to prevent a spark from turning into a fire.

The bigger picture: women’s peace work in policy and practice

Rahma’s story is not unique, and that’s exactly the point. Across the Horn of Africa, and indeed globally, women have long been central to informal peacebuilding networks, particularly in borderland and conflict-prone regions where formal institutions often falter. omen play a crucial role in providing early warnings of conflict by alerting the appropriate community actors. In Moyale, women frequently cross the border into Ethiopia for routine activities such as trade, visiting relatives, or participating in cultural events. This regular cross-border movement, combined with their cultural fluency, enables them to pick up on subtle signs of tension whether these be unusual gatherings, atypical livestock movements, or murmurs of grievances that may signal emerging conflict. This early warning function is not limited solely to cross-border threats; it also applies to potential conflicts arising from interactions with different communities on the Kenyan side. Upon detecting these early signals, women promptly return to their communities to mobilize local peace committees and inform local leaders of potential flashpoints.

Their work, however, is consistently under-recognised, underfunded, and under-reported.

In my research across the borderlands of Kenya and Ethiopia, particularly in Moyale, I encountered this paradox repeatedly. Women like Rahma are doing the critical work of de-escalating violence, providing first response, and maintaining cross-border dialogue, yet they remain largely excluded from formal peacebuilding mechanisms. County-level peace committees and national dialogue platforms are overwhelmingly male-dominated. When women are included, it is often in token ways, lacking decision-making power or sustained institutional support. Increasing the number of women in country level governance positions and requiring gender balanced teams for new county-funded projects in this part of Kenya could help to address the gender imbalance in decision making.

The barriers to inclusion are as structural as they are cultural. Women’s groups in the region frequently lack consistent funding, safe spaces to convene, reliable transport to conflict-affected areas, and access to early warning information channels dominated by local government or security actors. In Moyale, for instance, women peacebuilders often rely on their personal networks, phones, ad hoc transportation, and informal clan ties to respond to crises. Yet these grassroots systems are fragile, stretched thin, and rarely acknowledged by formal actors who continue to see peacebuilding through a masculinised lens of negotiation, disarmament, or enforcement.

And yet, research continues to affirm that when women participate meaningfully in peace processes, outcomes are more durable and inclusive. The challenge is not simply to “add women” to existing peace structures, but to reimagine peacebuilding itself: to centre the relational, affective, and community-based forms of mediation that women are already practicing.

Studies on local cross-border governance, however robust, may seem overly abstract when encountered in the form of a research report. This blog piece aims to counter such perceptions by demonstrating the relevancy of cross-border research. More specifically, it explains how, building on lessons learned from XCEPT-funded field research conducted between October 2023 and April 2024, Concordis International facilitated a series of peace conferences in 2025 between ethnic groups from the borderlands of South Darfur (Sudan) and the Central African Republic (CAR).[1]

At the time of the XCEPT research, those interviewed—including Concordis staff—emphasised that the affected communities were keen to engage in such dialogue as a means of moving forward. That aspiration has now become a reality.

The town of Um Dafoug sits on the border between Sudan and CAR.[2] The residents of the town and its surrounding areas make their livings through a mix of trades, including the seasonal migration of livestock (transhumance), which involves multi-ethnic cattle and camel herders moving their livestock across the border in search of pasture.[3] Against this backdrop, unregulated, poorly negotiated transhumance is a key instigator of inter-communal tensions.

North of the border, the hawakeer system—which predates colonialism in Sudan and governs tribal land ownership rights throughout Darfur—has contributed to local grievances among those pastoralist communities granted fewer land rights.[4] Particularly problematic has been the re-demarcation of land boundaries under Sudan’s President Bashir (in power from 1989 to 2019), which effectively transferred areas of land between tribal groups, perpetuating and in some cases escalating cross-border disputes related to livelihoods. Thus, segments of land east of Um Dafoug, formerly owned by Taaisha settled communities, have now become part of the Falata tribe’s territory. Typically, clashes between Taaisha and Falata communities occur when transhumant Falata return from CAR to Sudan at the start of each rainy season.

With state and international actors largely absent, local customary and religious elites have been left to play a central governance role in the CAR–Sudan borderlands. As such, localised agreements governing cross-border relations and livelihoods are predominantly unwritten and highly informal. At the same time, a variety of community mechanisms exist to mitigate tensions between and among pastoralist and farming communities. Ultimately, the overarching aim of these informal local agreements is to ‘manage (local) disorder’ in the CAR–Sudan borderlands.[5]

In 2021, there were a series of violent clashes between the Falata and Taaisha communities. In the wake of this, grassroots-level figures have called for acknowledgement of, as well as reparations for, losses suffered—both historically and more recently. This is seen by both communities ‘as a prerequisite to move’ forward. Locally-led negotiations have left the issue of reparations unaddressed, focusing instead on a fragile cessation of direct hostilities and the resumption of daily activities.

In 2024, a delegation of Taaisha leaders undertook a reconciliatory visit to the town of Tullus on the Sudanese side of the border, territory largely associated with the Falata. This led to the delegation and 50 Falata leaders pledging ‘to put aside their past grievances and embark on a new chapter of peaceful coexistence, fostering harmony among all tribes residing in four localities: Tullus, Demso, Um Dafoug, and Rehaid Albirdi’. This coincided with the February 2024 return of Taaisha-looted cattle, facilitated by members of a local, Concordis-established Advisory Group in Um Dafoug. These events precipitated a commitment to engage in further joint dialogue, with the ultimate aim of establishing joint mechanisms to govern access to land.

The Head of the Advisory Group, Omda Al Habib Altegani Omer, emphasised a conference between the Falata and Taaisha tribes should take place as soon as possible.[6] As a consequence, and at the invitation of the communities, Concordis worked in and around Tullus, Demso, Um Dafoug, Rehaid Albirdi and a fifth locality, Um Dukhan, to identify leaders who could bring the wider Taaisha and Falata communities together to engage in constructive dialogue.

In April 2025, Concordis facilitated extensive meetings in Um Dafoug, laying the groundwork for a possible cross-border peace conference with communities from Vakaga in CAR. The process involved over 200 community stakeholders, including traditional leaders, women, youth, herders and farmers. Between them, the participants identified various factors exacerbating clashes between CAR communities and herders, including prolonged stays, armed robbery and environmental degradation.

The meetings revealed a strong desire among the community for structured agreements, shared early-warning systems and inclusive decision-making. Women demanded safe migration routes and participation in peace structures, while herders emphasized the need for access agreements and corridor protection. On April 13th, Concordis brought together 112 participants from the five Sudanese localities and two cross-border representatives from CAR for a four day peace conference in Um Dafoug. Conversations were widened to maximize the chances of reducing violence, killings and burning of villages, participants included Omdas and Nazir-level leaders representing ethnic groups including the Taaisha, Falata, Beni Halba, Masalit, and Barno, alongside women, youth, and traders.

The discussions addressed early cattle migration (Talaga), land use disputes and accountability for theft. The conference produced concrete outcomes. Local authorities committed to:

During the process, Concordis applied a number of learnings on cross-border governance agreements gleaned during XCEPT-funded research.[7] Of particular importance are the following:

The process has become a live example of translating research into tangible peace infrastructure, especially in borderland areas with little state presence.

[1] The XCEPT research was facilitated by European Union funding as part of the ‘Zones frontalières pacifiques et résilientes III’ action across CAR, Chad, Cameroon and Sudan.

[2] The settlement on the CAR side of the border is known as Am Dafok, while the settlement on the Sudanese side of the border is variously translated from the Arabic as Um Dafoug, Um Dafuq or Um Dafok. All refer to the same place.

[3] Louisa Lombard, ‘The Autonomous Zone Conundrum: Armed Conservation and Rebellion in North-Eastern CAR’, in Making Sense of the Central African Republic,eds. Tatiana Carayannis and Louisa Lombard, London: Zed Books, 2015; Stephen W. Smith, ‘CAR’s History: The Past of a Tense Present’, in Making Sense, Carayannis and Lombard, 40.

[4] See Mohamed Dawalbit, ‘Narratives that Drive Conflict – Unpacking the Term “Settler” and What it Means in Darfur’, The Conflict Sensitivity Facility, 6 February 2024. https://csf-sudan.org/settler-in-darfur/.

[5] Allard Duursma, ‘Making Disorder More Manageable: The Short-term Effectiveness of Local Mediation in Darfur’, Journal of Peace Research 58/3 (2021): 554–567; Jan Pospisi , ‘Dissolving Conflict. Local Peace Agreements and Armed Conflict Transitions’, Peacebuilding 10/2 (2022): 1–16.

[6] Advisory Group Work Plan, February 2025, available on request from [email protected].

[7] Concordis International, ed., Recognising the Local in Borderland Governance, London: Concordis International, 2025.

On 9 April 2025, two advertising billboards located on the road to Beirut airport were set on fire, just days after they had been installed.1 The billboards had displayed a Lebanese flag and the message ‘A New Era for Lebanon’ (عهد جديد للبنان), superimposed onto an aerial image of the Bay of Jounieh. The airport road runs through Dahiyeh, the southern suburbs of Beirut, and has long been adorned with posters commemorating Hezbollah and Lebanese resistance against Israel. Prior to the ‘New Era’ campaign, the same billboards had displayed posters celebrating Hezbollah’s former Secretary General Hassan Nasrallah and former Head of the Executive Council Hashem Safieddine as martyrs, after their assassinations in Israeli airstrikes last year.

The agency which owns the billboards has not named the new campaign’s sponsor – although the ‘New Era’ slogan likely refers to a statement given by Joseph Aoun after he won Lebanon’s presidential election in January 2025 – and stated that the change in posters was not political. Rather, it was due to the expiry of the existing contract, dated one week after the funerals of Nasrallah and Safieddine in February. Nevertheless, the timing and placement of the new advertising campaign provoked strong reactions. Some viewed the transition as a ‘victory’ in ‘cleaning’ the airport roads of pro-Hezbollah messaging.2 For others, the move constituted an attempt to deny the realities of the ongoing conflict. As one Beirut resident reflected, ‘Why [A New Era for Lebanon]? They finally elected a prime minister, so what? What’s this future? As long as Israel exists in Lebanon, we won’t have a future’.

Lebanon has long been divided by a history of sectarianism and violence, and tensions have become exacerbated during the recent conflict with Israel. Just days after the billboards were destroyed, however, the Beirut municipality issued a new initiative to promote a narrative of national unity. On the orders of Lebanon’s Interior Minister Ahmad al-Hajjar, it was announced that all sectarian posters, banners, photos, flags, and advertisements placed on public property along Beirut’s central district were to be removed in order to make Beirut ‘a city free of sectarian and party slogans’.3

As the response to the ‘New Era’ campaign shows, however, Lebanese approaches to memorialisation of the recent past and to the ongoing conflict with Israel are diverse and divisive. By introducing a national narrative of unity, without first seeking to repair existing divisions or address the challenges currently facing Beirut’s population, the government risks exacerbating tensions rather than overcoming them.

Political images have long been a common feature of Beirut’s urban landscape. Most writings on political Lebanon and memorialisation do not fail to acknowledge the ‘walls continually adorned with banners, posters, portraits immortalising iconic images and infamous slogans, an informal cornucopia of the “living dead”’.4 These visual displays are a means by which Beirut’s residents can express loyalty, demonstrate their political identity, and commemorate the dead. However, they also play a role in what Meier has described (in the context of south Lebanon) as ‘borderscaping’: a marking of territory or boundaries through the use of political iconography.5

In speaking with a number of residents of Beirut in May 2025, the majority agreed with the decision to remove party political insignia from the capital. This did not seem to be out of a desire to limit expressions of identity. As 34-year-old Farid explained, ‘I totally understand that people want to showcase the loved ones they lost. It’s understandable. I feel like it shouldn’t be on the highways on the main roads. It can be in a more you know like local scale, in a more private manner’.

Instead, approval of the directive was linked to the way in which political imagery in Beirut often represents an expression of power, and a suppression of freedom, in the areas in which it is displayed. Hadi, a 29-year-old Sunni resident of the Hamra district of Beirut, claimed that posters constitute an unofficial demarcation of ‘go’ and ‘no-go’ areas for different sectarian backgrounds: ‘I think it’s a surface issue, but at the same time, I would, personally, when I go into an area and I see that it’s predominantly this group or that group, or if it’s a contested area and one group is trying to impose itself, I do feel a bit tense’.

Kataeb party flag. Credit: Brontë Philips.

Similarly, Hassan, a 23-year-old from a Shi’a family background, remarked that, ‘in my opinion, one of the biggest ways of strong-arming the people in a local area to be afraid of portraying their political opinion is by putting up political posters that claim to represent the entire area’.

The area of the airport road, in this context, is symbolic – not only as a public space, but as one of the first vistas for those entering Lebanon. For some Beirut residents, the removal of party political posters in this iconic gateway to the country constitutes an important representation of Lebanon. As 28-year-old Farah reflected, ‘I don’t think you would feel safe if you see a terrorist picture on a billboard right when you are entering the country. So I think it’s important that they are being removed’.

In the context of Lebanon’s conflict memory, however, the removal of party political posters, and the promotion of ‘A New Era for Lebanon’, can also be interpreted as a continuation of what Khalaf has described as the ‘collective amnesia’ of post-civil war Lebanon.6 The Ta’if Agreement, signed in 1989 to mark the end of the conflict, effectively imposed a policy of state-sponsored silence on the violence of the civil war.7 It implemented a power-sharing arrangement which reinforced the political sectarianism of the civil war and empowered the same elites who were responsible for violence to control the narratives of that violence. The subsequent amnesty law, which pardoned many of the same sectarian leaders, meant that the conflict had no public resolution.

Yet, rather than contain and suppress the collective trauma of the civil war, the state-imposed silence created a memory vacuum which, in turn, facilitated a proliferation of memory cultures. Today, these competing narratives continue to maintain and perpetuate tensions among the population. For some, both the new advertising campaign – which has been rolled out across Beirut – and the directive, were believed to be another attempt to erase the realities of conflict and division in Lebanon. As 30-year-old Mona observed, ‘you can’t remove the political parties from Lebanon. You can’t remove the support, the years of integration, and the years of brainwashing. You cannot remove that by taking down a few posters’.

Similarly, with the ‘New Era’ campaign functioning as a (literal) plastering over of the wounds of conflict with Israel, it seems to some as though they are being encouraged to forget their experiences of the recent, and ongoing, hostilities. This deprives people not only of a chance to address their trauma, but to take steps to begin to heal. Mona viewed the promotion of a new collective narrative of unity as an official silencing of trauma which ‘denies us time to grieve over what just happened’.

As well as ignoring existing issues, there is a concern that the new initiatives could reignite schisms. 28-year-old Ali, a Shi’a resident of Beirut, expressed fears that the efforts to remove political insignia could backfire: ‘I think in general, regulations would not solve the issues, but it would create suppression that would lead to more extremist [views] – especially when one sect feels that it’s a victim during and after the war’. In this case, attempts to promote a facade of unity may in fact deepen feelings of exclusion, as they deny the population the chance to hold an honest dialogue about the scars of recent conflict memory.

Martyrs’ Square, looking towards Al-Amin mosque. Credit: Brontë Philips.

Even among those who agreed with the municipality’s efforts to remove party political iconography, many were sceptical about whether the initiative would be effective. The directive does not constitute a removal of images across the whole of Beirut. Posters celebrating the Kataeb party remain in several areas, while images of Bashir Gemayel, as well as Lebanese Forces flags and icons, are still displayed in areas such as Achrafieh. In some cases, while party flags are taken down, images of leaders, such as Nasrallah and Nabih Berri, remain. As Hadi recalled, ‘10 years ago they did the same thing. There was a thawing of ties between the Future Movement and Hezbollah, and they didn’t fix any of their primary disagreements, but they agreed to remove their posters … this lasted maybe a month or two before all the posters started to reappear magically’.

Hadi also expressed doubt as to whether the removal of sectarian signs would contribute to any rehabilitation of social divides, particularly where these had been exaggerated in the wake of the recent conflict with Israel: ‘I’m pretty sure they have other avenues of brainwashing those people … Not just Hezbollah, the Christians, the Sunnis. They have other avenues: schools, clubs, scouts. That’s why I think it’s just like a surface issue, and I’m sure they’re going to be back as soon as the going gets tough, those posters’.

The ‘New Era’ campaign, while celebrated by some as a reclamation of national sovereignty, has also increased feelings of disillusionment towards the new administration. With the government seemingly choosing to tackle the country’s divisions on a superficial level only, many of Beirut’s residents feel let down. As one social media user wrote on X, ‘No one has time for martyrs, reconstruction, the South or the occupation … [Some] are busy decorating the airport road so tourists can enjoy their stay in Lebanon’. Likewise, Hadi claimed that ‘I just think it’s a very cheap gimmick to attract tourists, and this is just another thing that I’m bothered with, that the government cares more about tourists than its own people’.

![A photo taken through a car window shows a poster which displays an aerial image of the Bay of Jounieh, with text and an image of the Lebanese flag superimposed on it. The text reads: عهد جديد للبنان [translates to: A New Era for Lebanon]](https://icsr.info/wp-content/uploads/2025/07/A-new-era-for-Lebanon-airport-road-2-1-1.jpg)

‘A New Era for Lebanon’ poster on the airport road. Credit: Brontë Philips.

The new initiatives may signal hope for a change in Lebanon’s circumstances, but many of those interviewed feel these displays of optimism are premature and fail to address the reality of the situation. Despite the ceasefire agreed in November last year, Israel still occupies five positions in Lebanon and continues to launch airstrikes at what it claims are Hezbollah targets.8 Lebanon is also desperately seeking funding to support its recovery and reconstruction, which is projected to cost around $11billion USD.9 It is not clear how, or when, Lebanon can build a more stable and unified future. As Hassan highlighted, ‘there is a lot of steps you need to do before tearing down the political posters and replacing them with ultra optimistic “yeh we’re coming back blah blah” posters … you’re not going to wave a magic wand and make Lebanon great again. The people are hurt, they’re tired, they’re injured’.

For Mona, the initiatives are simply another attempt to incorporate the current conflict with Israel into a cycle of violence, forgotten and re-remembered: ‘I think that, as Lebanese people, we’re always trying to start over, and we’re always trying to push everything under the rug. We’ve seen it with the civil war. We’ve seen it with the 2006 [Israel-Lebanon] war. We’ve seen it with this war … how very Lebanese of us, to turn the page’. If the Lebanese state wants the visual displays of unity to truly reflect the reality on the ground, it cannot simply paper over its divisive history. Instead, it must work to promote an honest and inclusive dialogue amongst its population, and allow the Lebanese people to openly share their memories and experiences of conflict to allow them to move forward.

*Pseudonyms have been used throughout to protect the identity of those interviewed.

This article was originally published by the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation (ICSR) at King’s College London.

June 12, 2025

Modern conflicts are no longer neatly contained within national borders but are increasingly shaped by complex, transnational geoeconomic systems. This event marks the culmination of a five-year Chatham House research programme under the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy, and Trends (XCEPT) initiative funded by UK international Development. The research explores the evolving dynamics of transnational conflict ecosystems across the Middle East, North Africa, the Sahel, and parts of West and East Africa. The programme investigates how conflict economies — sustained by both licit and illicit supply chains — are reshaping regional power structures and challenging the effectiveness of traditional Western policy responses. As regional middle powers pursue pragmatic, issue-based alignments and military actors evolve into significant political players, the urgency for a more adaptive and strategic Western approach grows.

Speakers:

In recent years, high-resolution satellite imagery and geospatial analysis have become increasingly valuable tools in documenting the effects of conflict, including the widespread destruction of infrastructure, property, and lives in Ukraine, Gaza, and Sudan. In January, satellite imagery played a pivotal role in the U.S. Department of State’s determination that members of the Rapid Support Forces (RSF) and allied militias had committed genocide in their attacks against non-Arab communities in several locations in Sudan. Most recently it has been used to document the damage caused by missile and drone strikes in the ongoing India and Pakistan conflict.

Conducting research on sensitive or contentious issues in fragile and conflict-affected areas where demographic data is flawed, access to remote and insecure areas is challenging, and representative samples prove particularly elusive is a perennial problem. In these terrains, fieldwork is typically limited and skewed by security concerns and the associated costs, and it is often the voices of elites that are the loudest and most prominent. The Farsi phrase “Can hearing ever be like seeing?” reflects the greater weight that should be given to the things we can see for ourselves, compared to what we are told.

To this end, satellite imagery and informed analysis can be usefully deployed to study complex and sensitive issues in fragile and conflict-affected areas and support more effective policy development. While imagery is not a substitute for talking to the people directly impacted by conflict, our research on the outbreak of heavy fighting between Iran and Afghanistan in May 2023 shows that it is a critical tool in developing a better understanding of these complex terrains, where the loudest voices can dominate the media and social landscapes and skew research findings—and, all too often, policy outcomes.

Background to the Conflict

In May 2023, heavy fighting broke out between Iranian and Taliban forces on the border between Afghanistan and Iran. At the time, the media and many analysts looked to explain the incident as a result of the escalating “war of words” in the week before between senior officials in the Taliban and the Iranian Republic.

As is common during dry years, the Iranian authorities complained that Kabul had retained more than its fair share of water from the Helmand River, depriving farmers and communities across the border in the province of Sistan and Baluchistan in Iran. Under a treaty signed by the two nations in 1973, the water is a shared resource. The Iranian president at the time, Ebrahim Raisi, warned “the rulers of Afghanistan to give the water rights to the people of Sistan and Baluchestan,” prompting responses from senior Taliban officials.

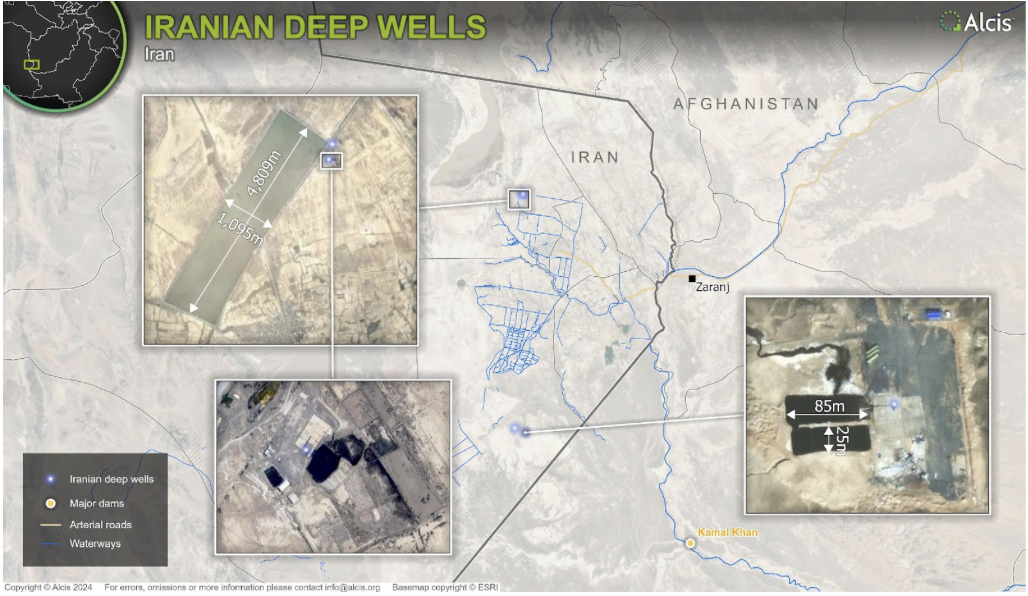

Rather than focusing on the rhetoric surrounding the dispute, our research revealed novel insights into the conflict by focusing on concrete facts that could be observed through satellite imagery. Our research pointed to a more localized dispute about border management and the challenges of recalibrating cross-border relations following the collapse of the Afghan Republic and the subsequent Taliban takeover, and revealed far more pervasive issues with the widespread and unsustainable exploitation of groundwater across the Helmand River basin.

Disparities Between Observation and Discourse

The use of geospatial analysis in our research helped us better understand the accuracy of the competing narratives that authorities in Tehran and Kabul look to convey when complaining about transboundary water rights in the Helmand River Basin.

Typically, disputes between the two countries begin with the Iranian government accusing authorities in Kabul of withholding water from the Helmand River and failing to comply with their treaty obligations. Kabul authorities generally suggest the reduction in water flow is a function of drought, noting that there is a provision in the Helmand Treaty to reduce water flows under such conditions.

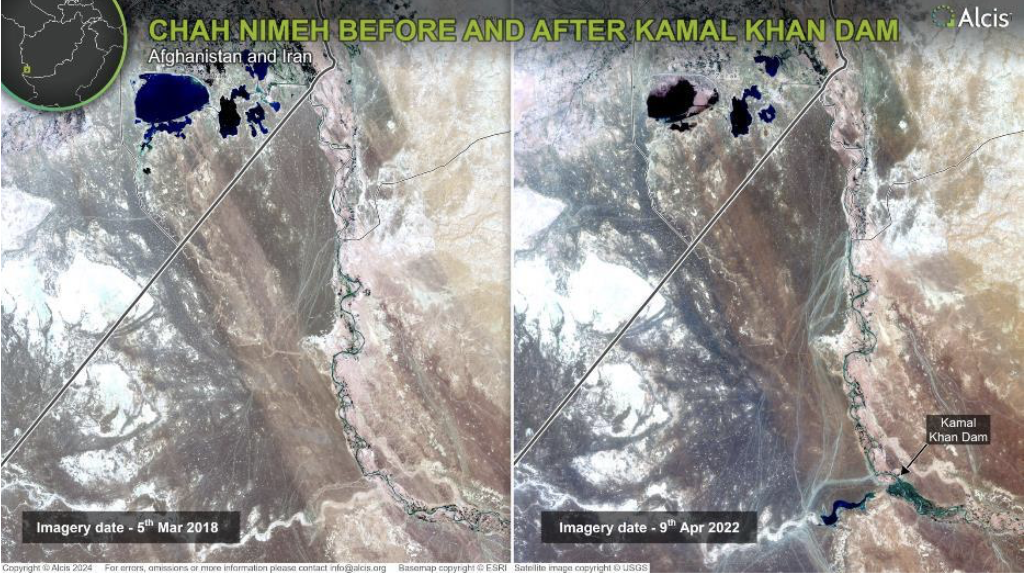

Tehran alleges that Afghanistan’s ability to store and divert water—through infrastructure projects such as the Kajaki Dam, constructed in the 1950s, and more recently the Kamal Khan Dam, built in 2021—has prevented sufficient water from being discharged into Iran for use by the population of Sistan and Baluchestan.

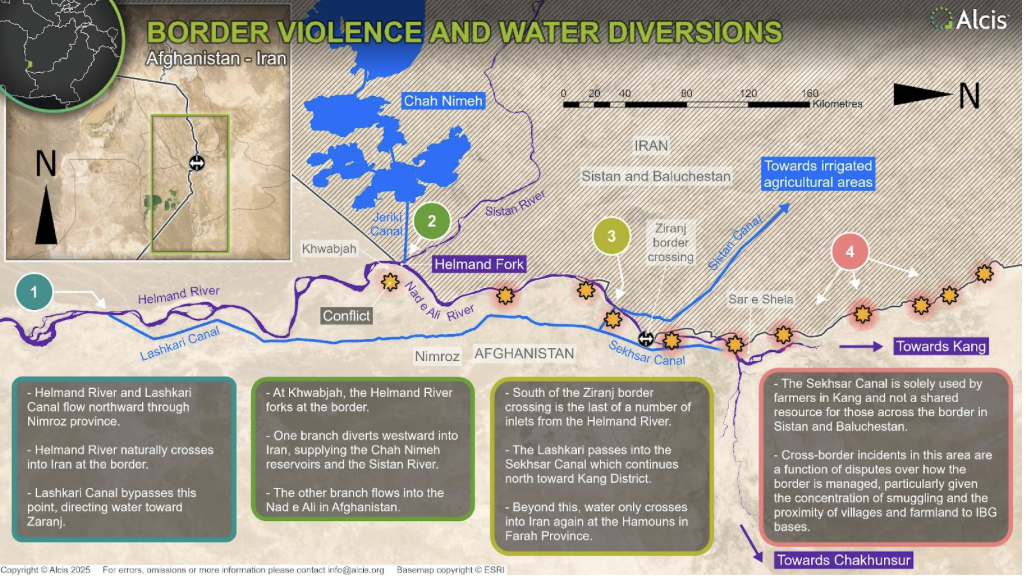

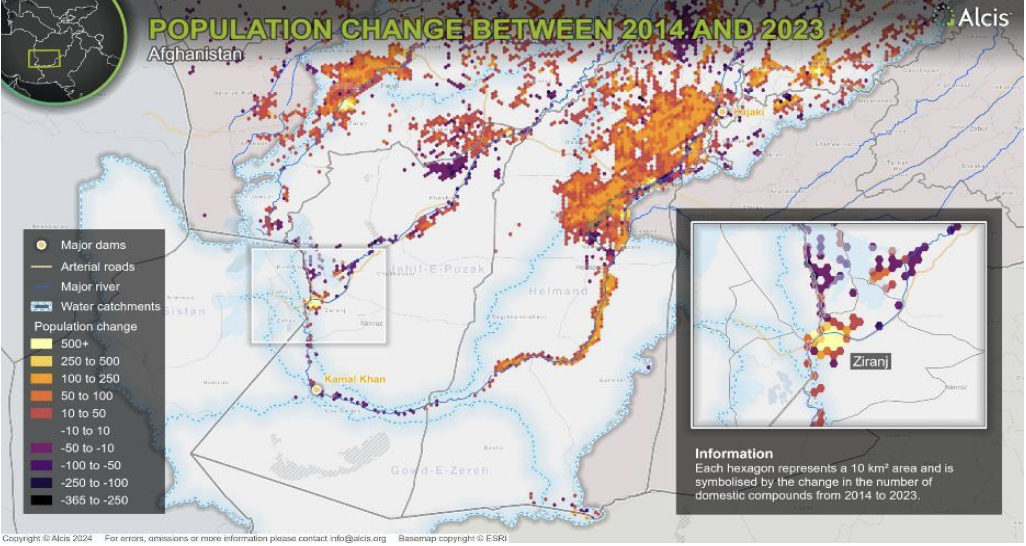

There is some truth to this complaint, especially since the completion of the Kamal Khan Dam. As satellite imagery has shown, this latest dam, constructed in the lower part of the Helmand River Basin—just upstream from the Helmand fork—now allows Kabul to release water from the Kajaki Dam in the upper basin to be used by communities downstream in Afghanistan while retaining any remaining discharge at Kamal Khan, and preventing it from flowing to Iran (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Chah Nimeh before (2018) and after (2022) the commissioning of Kamal Khan Dam. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

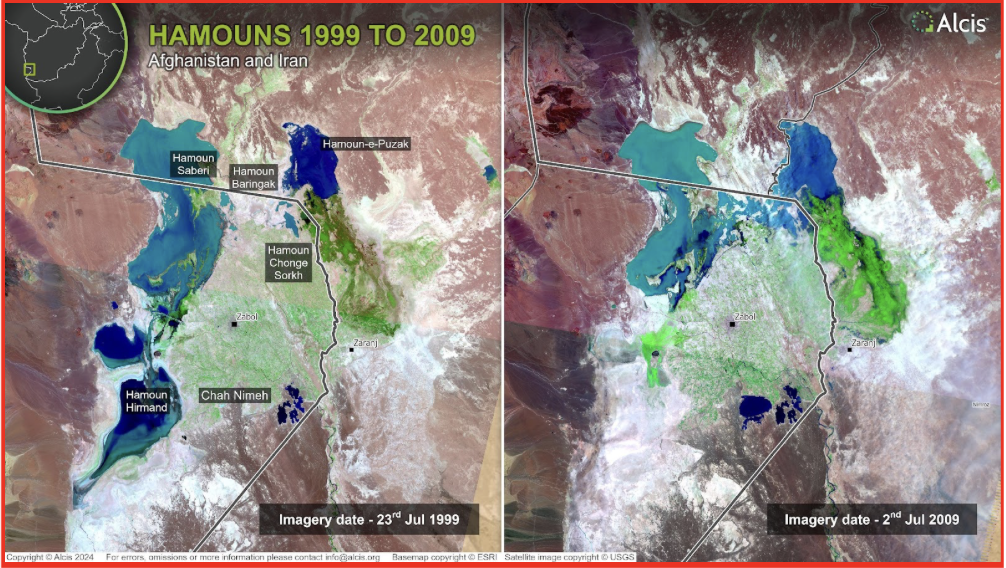

Further imagery analysis has shown that any efforts by the Afghan authorities to retain and divert water have been mirrored on the Iranian side of the border—often, some years earlier. For instance, the Jeriki Canal and Chah Nimeh reservoirs in Iran, located after the Helmand fork—where the Helmand River first meets the Iranian border—were initiated in the 1970s and 1980s, respectively, to divert and store water, mainly for the urban populations of Zabol and Zahedan. Before the construction of the Kamal Khan Dam in Afghanistan, these reservoirs captured the water once released from the Kajaki Dam. The construction of the Chah Nimeh 4 reservoir in Iran in 2008—which more than doubled storage capacity—subsequently significantly reduced the water flow into the Nad-e-Ali River and Hamoun-e-Puzhak in Afghanistan, and the Hamoun-e-Saberi in Iran (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Impact of construction of Chah Nimeh 4 on the hamouns. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

Consequently, while historically Tehran has argued that it is Kabul’s failure to release water from Kajaki that limited water flow to the hamouns—a series of terminal lakes and salt marshes—and Sistan and Baluchestan province, its own infrastructure efforts at the Helmand fork have been more detrimental to the rural livelihoods of the downstream populations in both Afghanistan and Iran. Indeed, Iranian authorities tend to prioritize the populations of Zabol and Zahedan; water is released from the Chah Nimeh reservoirs to farmers in Sistan and Baluchestan for irrigation only after the needs of the urban population have been met.

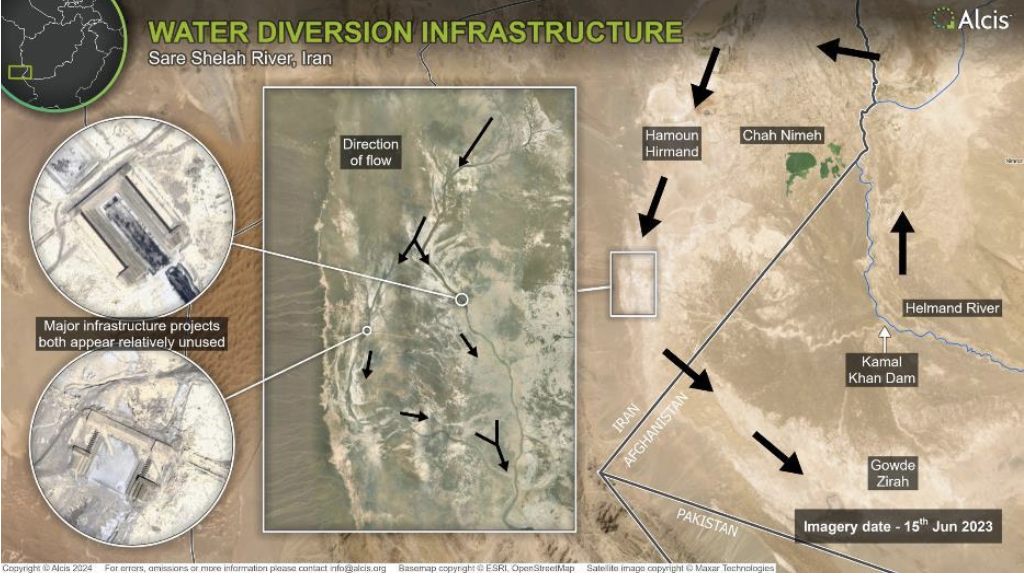

Through imagery analysis, it is also clear that Tehran sought to stem the flow of water from the Hamoun-e-Hirmand through a series of dams on the Sar-e-Shelah River in the district of Hamoun in Sistan and Baluchestan province (Figure 3). As such, while Tehran accuses Kabul of seeking to retain and divert water to its advantage and to the detriment of downstream populations in Iran, Tehran has been doing the same for longer and—until the completion of the Kamal Khan Dam—perhaps more effectively. While Tehran’s complaints have intensified since the completion of the Kamal Khan Dam, it is inaccurate for Tehran to portray itself as the sole victim and Kabul as the sole perpetrator.

Figure 3. Dams on Sar-e-Shelah River constructed circa 2001, redirecting water from flowing toward Gowd-e-Zirah. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

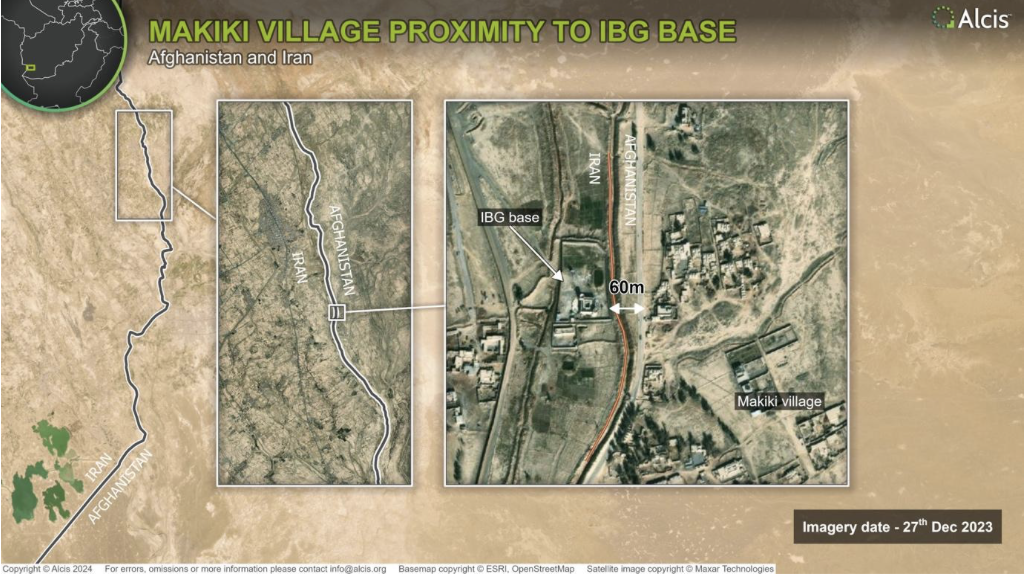

Imagery analysis also revealed that the fighting between Afghan and Iranian forces began in an area where the border populations do not even share common water sources but rather where there is a long tradition of cross-border smuggling (Figure 4). It shows just how close the Iranian border wall is to Afghan farmland and villages, often as little as 60 meters apart. The construction of this border wall increased the potential for the Iranian Border Guards (IBG) to fire across the border and, following the Taliban’s capture of Kabul, increased the likelihood that their battle-hardened soldiers would return fire.

Figure 4. Water flows on the border from Kamal Khan to Kang. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

Further satellite imagery exposed the increased number of catapults used to propel drugs into Iran along this stretch of the border following the Taliban takeover, an indicator of their tolerance of the cross-border trade—a source of increasing frustration among the IBG and, ultimately, the direct cause of the fighting (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Proximity of farmland to Afghan border posts and Iranian border gates near Makiki village. Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

Implications of Reduced Surface Water

Perhaps most important, satellite imagery and geospatial analysis were instrumental in identifying how communities in Afghanistan and the Iranian state have responded to a reduction in surface water in the Helmand River Basin through widespread groundwater exploitation and the threat this now poses to the lives and livelihoods of communities across southwest Afghanistan and in Sistan and Baluchestan in Iran.

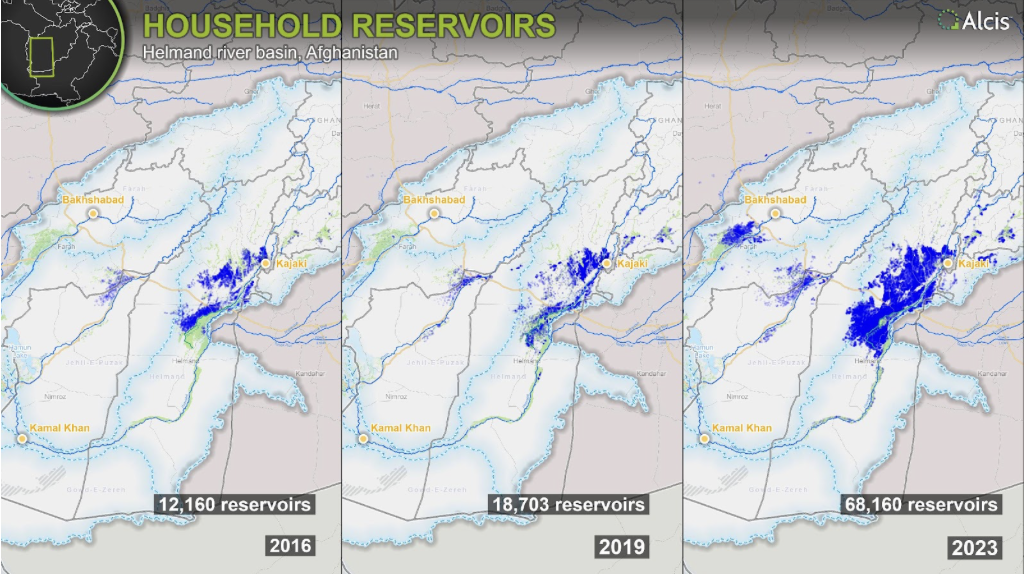

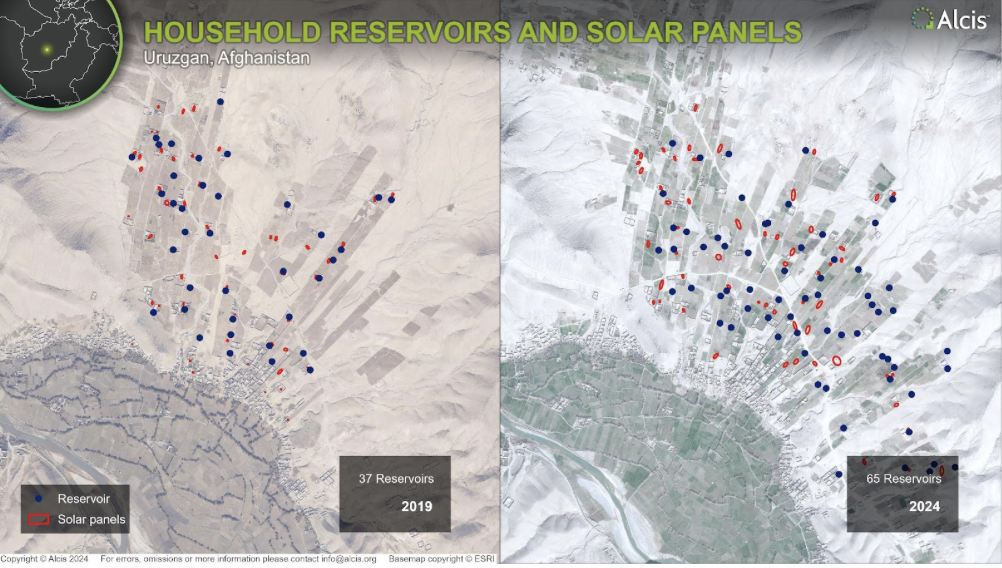

In Afghanistan, access to affordable solar-powered systems has been transformative and has led to ever greater numbers of Afghan farmers installing deep wells and extracting groundwater. Only a meter in diameter, many wells are more than 100 meters in depth and have water drawn from them using a pump powered by multiple arrays of solar panels. While underground, these wells often leave a visual signature—a surface reservoir and solar panels—that can be identified and then mapped using imagery (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Household reservoirs used by those using solar-powered deep wells to extract groundwater (2016, 2019, and 2023). Copyright Alcis. Republished with permission (on file with Lawfare).

Imagery shows that by 2023, there were at least 68,160 deep wells in the Helmand River Basin—five times more than in 2016. While these were at one time used only by farmers looking to settle remote former desert lands in the southwest provinces of Helmand and Farah—often to grow poppies—these deep wells have become ubiquitous, commonly used in surface-irrigated areas where water flows have become increasingly unreliable due to climate change.