In 2011, a brutal conflict between Sudanese government troops and Sudan People’s Liberation Movement–North (SPLM/N) fighters in the Nuba Mountains region forced civilians caught up in the violence to flee across the border to South Sudan.[1] There, in Yida—the first of three refugee camps to be established in the area—the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) saw to the basic needs of those who had been displaced, including their food, shelter, health and education. Refugees were also able to cultivate crops using handmade farming tools, with the fertile land in Yida camp providing consistently good harvests.

Previously, children living in the Nuba Mountains were often involved in unpaid household work such as bricklaying, cattle-grazing and farm work. Having been displaced, however, the comprehensive international support provided—which extended to unaccompanied children separated from their parents—meant this practical assistance was no longer needed.

In 2020, the long proposed resettlement of refugees living in Yida camp brought an end to UNHCR support. As a consequence, many children in Yida—and increasingly the other two camps as well—have had to seek paid work in order to supplement their family income. Such employment, which can often take children beyond the confines of the camp, includes building work, assisting Bagara nomads with cattle-grazing, and selling poles, grass or charcoals. In undertaking such tasks, children are frequently exposed to financial exploitation and dangerous conditions, placing them at risk of physical and emotional harm. Moreover, the dire economic situation faced in the camp has led to rising numbers of girls and young women having to submit to forced and/or early marriage.

Given the current Sudan war has led to a new wave of displaced people seeking refuge in South Sudan, there is a very real possibility that these dynamics will be further exacerbated over the coming months unless appropriate action is taken. This blog is based on XCEPT research in 2024 involving extensive interviews with Nuba Mountains refugees on South Sudan’s border to understand these dynamics.

Yida, Ajuong Thok and Pamir camps were established in South Sudan’s Ruweng administrative area in order to host refugees escaping the Nuba Mountains conflict.[2] Yida camp served as the main entry point from South Kordofan, and initially hosted 20,000 refugees—mostly survivors of the Kadugli massacre in June. Shortly afterwards, in November 2011, the Sudanese air force provoked international outrage by dropping two bombs on Yida camp, killing 12 refugees and injuring 20. By 2013, the camp’s population had increased to 71,000, the vast majority of whom were women and children.

In March 2013, UNHCR and South Sudan’s Commission for Refugees Affairs established Ajoung Thok camp, which initially held 24,000 refugees and currently hosts over 55,000 refugees.[3] The last of the three camps to be set up was Pamir in September 2016, which was intended to host refugees relocated from Yida camp. Having started out with 34,000 refugees, the camp is currently home to more than 50,000 people, its population swelled by new arrivals escaping the ongoing war in Sudan.[4]

In 2016, UNHCR and the South Sudanese government announced that, given chronic overcrowding issues, the security implications of the camp’s location 20 km from the border with Sudan, and the fact Yida had never been officially recognized as a refugee camp, its inhabitants were to be relocated elsewhere. The Nuba refugees rejected relocation to Ajuong Thok and Pamir, however, arguing the two camps were too close to the border area controlled by the Sudanese government, and that at least Yida was close to SPLM-N authorities in the Nuba Mountains.

Despite these objections, the formal relocation process was eventually set in motion: in October 2019, UNHCR discontinued its food assistance in Yida, and two months later Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) stopped its medical services. By 2020, refugee schools had been left in the hands of the South Sudan state government, with water and sanitation handed over to local authorities and the refugee community.

During the course of 2020, just 2,758 Yida refugees were relocated to Pamir. Although children could continue to access free education in Pamir, the food ration there was halved from four to two malwas (gallons) of sorghum per person per month, further discouraging Yida refugees from resettling. The relocation has since led to a number of negative impacts for the refugees remaining at Yida, while those living in the two newer camps are also facing increasing hardship. Access to water has become more difficult, while clinical drugs are harder to find, forcing many to turn to herbal medicine.

Of particular concern when it comes to children is the loss of access to free education. Government school fees were initially set at USD 1 and USD 2 per term respectively for primary and secondary schools (based on three terms per school year). These fees have since increased to USD 3 and USD 5 respectively. Many parents, who are already struggling to provide enough food for their families, simply cannot afford these rates.

As a consequence, many children are now having to take up paid work or are leaving home to seek a better life, whether inside the camp or further afield, in Parieng, Liri, Rubkona or the Nuba Mountains.

In the past, children living in the Nuba Mountains region would often be expected to participate in domestic tasks as a means of passing on necessary skills for later in life.[5] For instance, children with pastoralist parents would likely be involved in camel, goat, sheep, cow or donkey rearing, while the children of farmers might be given small plots of land to tend. Other household duties assigned to children included hunting, fishing and collecting wild fruits or firewood. Despite these responsibilities, children (those aged 5–17 years) still had sufficient time to play with their friends.

More recently, having a formal education has acquired greater importance, with most parents keen to ensure their children go to school. When the 2011 war erupted, many Nuba people migrated to South Sudan partly to ensure their children could continue to access a school education.

Today, however, children from poorer families are having to work not to acquire skills, but simply to earn money. One avenue of employment is bricklaying. This would previously have been viewed as man’s work, but the pressures wrought by displacement, the war in Sudan and inflation in South Sudan mean women and children now have to engage in this often back-breaking work for meagre wages.

Another way in which children can make money is assisting Bagara nomads. In this scenario, the refugee parents agree to let the nomad take their child away for the purposes of helping graze their animals, sometimes for months on end. The child is paid a he-goat (worth about USD 100) for every month they work. The he-goats are usually then sold by the parents in order to buy sorghum to supplement the family’s diet, or purchase shoes, medication and soap for other siblings. Having to spend months away from home inevitably means the children assisting the Bagara nomads must forego their education.

According to UNHCR refugee law, refugees are not supposed to return to their countries of origin or even leave the camp to travel to other parts of the host country. The growing difficulty of meeting daily needs has, however, driven many refugees to move to Liri (in Sudan) in search of farming jobs. Commercial farm owners in Liri offer reasonable wages, equivalent to about USD 5 per day. In this scenario, children mostly cross over to Liri with adults, siblings or friends who have previously worked there. Older children (aged 12–17) are sometimes given accommodation by the commercial farm owners for the duration of their employment, following which they return to their camp and give the money they have earned to their parents. Alternatively, children may work alongside their parents before crossing back together.

Refugees arriving in Yida camp between 2011 and 2019 were provided with accommodation by UNHCR. Since then, however, refugees have had to build shelters themselves. In light of this, refugees—children included—have taken to collecting poles and grass from the nearby forest, which they then sell. Some are also involved in building structures for host community members, receiving the equivalent of USD 20 for each one they build. Other refugees have sought to make money by collecting firewood and making charcoal.

Again, tasks such were previously the preserve of adults, and only conducted by children for training purposes under the supervision of their parents. Now, financial imperatives mean it is commonplace for children, even younger ones, to take on these physically arduous tasks for money.

As already touched upon, there are a number of negative implications to children in refugee camps undertaking paid work. Most obviously, they will have less time and energy to attend school or complete homework.[6] Thus, in attempting to meet short-term needs, they end up compromising their long-term futures, perpetuating the cycle of poverty endured by their families.

Children forced to spend long hours engaged in strenuous work also risk suffering serious physical and mental health issues.[7] Mental disorders such as depression and anxiety have become commonplace among children in Ajuong Thok, Pamir and Yida camps, often—according to a focus group discussion with youths[8]—induced by injuries sustained through paid work and the lack of appropriate medication they receive afterwards.

In addition, many of the children who reside at their workplace end up sleeping without a mosquito net, rendering them susceptible to malaria and other chronic diseases.

Back when they used to live in the Nuba Mountains, children were almost entirely exempt from paid work. Now, the pressures of war, ongoing displacement, inflation, insufficient harvests and a lack of support from both the South Sudan government and international organizations mean refugee children—particularly those in Yida—must prioritize making money over pursuing an education.

If this state of affairs is to be reversed, then the government and NGOs must intervene to provide fully funded educational support to refugee children, especially those in direst financial need. In doing so, concerted efforts must be made to incentivize schooling over paid work.

[1] Sudan Human Security Baseline Assessment (HSBA). www.smallarmssurvey.org/project/human-security-baseline-assessment-hsba-sudan-and-south-sudan.

[2] UNHCR, ‘South Sudan: Yida refugee settlement profile’, 28 February 2020. Accessed 23 January 2025, https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/74632.

[3] UNHCR, ‘South Sudan: Ajuong Thok refugee camp profile’, 28 February 2020. Accessed 23 January 2025, https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/74627.

[4] UNHCR, ‘South Sudan: Pamir refugee camp profile’, 28 February 2020. Accessed 23 January 2025, https://data.unhcr.org/en/documents/details/74631.

[5] L. Aquila, ‘Child Labour, Education and Commodification in South Sudan’, Rift Valley Institute, 2022. https://riftvalley.net/publication/child-labour-education-and-commodification-south-sudan/.

[6] Olivier Thévenon and Eric Edmonds, ‘Child labour: causes, consequences and policies to tackle it’, OECD working paper, November 2019.

[7] Anaclaudia Fassa et al., ‘Child Labor and Health: Problems and Perspectives’, International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health 6: 1 (2000), 55-62.

[8] FGD with Rawada, Fatuma, Alamin, Idriss, Samarn, Naina and Jalla, Yida, 12 June 2024.

Since the 2011 Libyan revolution, the country has endured waves of conflict. As an integral linkage between Africa and Europe, international media highlights a growing migrant crisis through Libya – attributed to a human smuggling and trafficking sector regulated by various local actors.

In this episode, Tim Eaton and Lubna Yousef discuss their latest research on how transnational human smuggling has fuelled conflict in Libya through a systems analysis of three key transit cities – Kufra, Sebha and Zawiya. Using this approach, their research examines the roles played by conflict and social dynamics in the expansion of human smuggling and trafficking – thus helping uncover critical gaps in policies aimed at addressing the rapid rise of migration.

This episode is available on Soundcloud, Apple Podcasts and Spotify.

Kheder Khaddour is a nonresident scholar at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut. His research is focused on civil military relations and local identities in the Levant, with a concentration on Syria. Most recently, he co-authored a major paper on Syria’s borders with Armenak Tokmajyan, titled, “Borders Without a Nation: Syria, Outside Powers, and Open-Ended Instability.” Diwan interviewed him in early February to get his perspective on the Syrian-Lebanese border, which has been the site of cross-border conflict in recent weeks.

Michael Young: How has the downfall of the Assad regime in Syria affected the situation along the Syria-Lebanon border?

Kheder Khaddour: In the months leading up to the fall of the Syrian regime, Israeli airstrikes intensified along the border, including those targeting official border crossings. These attacks weakened Hezbollah’s capabilities. The regime’s collapse created a new security reality. Groups operating under the supervision of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham took control of the official border crossings and their combatants spread across all the border areas, replacing Hezbollah militants and the former Syrian army and security forces. This created an extremely fragile security situation on both sides of the border. On the one hand, the Lebanese state’s authority had always been weak in these areas, and on the other, the groups that took control of the Syrian side had a militia-based structure.

MY: Recently, there has been fighting in border areas. What has been the cause of this?

KK: The most recent round of fighting has been concentrated in the areas of Qusayr in Syria and the Hermel area of northeastern Lebanon. The most crucial factor here has been demographics. There is a mix of Shiite and Sunni villages in these areas. Hezbollah entered Syria through Qusayr in 2013, but the focus today is not on the city itself but primarily on the area west of the Orontes River. In this region, there are mainly Shiite villages populated by Lebanese, whose inhabitants have owned land on the Syrian side of the border for decades. The area, which served as a gateway into Syria during the Syrian conflict, is today the place of armed confrontation between members of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and Shiite families such as the Jaafar and Zeaiter clans. These conflicts reflect the ongoing sectarian tensions that have persisted since the outbreak of the Syrian war in 2012.

MY: Smuggling has long been a problem along the border, and recent reports indicate that it is continuing. What are the implications of this for the new Syrian government? Is it in a position to bring such activities to an end?

KK: Smuggling has been a main problem since the establishment of the border between Syria and Lebanon. There are two types of smuggling. First, smuggling involving essential goods, which has never stopped and is linked to price differentials between markets in the two countries. Currently, in the middle of a tense security situation, smuggling networks are transporting goods such as diesel fuel and poultry from Lebanon into Syria. Hundreds of families on both sides of the border depend on this trade for their livelihood. The second type of smuggling is political in nature, and includes weapons, drugs, and people. This has completely stopped in the last two months given the removal of the Assad regime and Hezbollah’s inability to engage in cross-border activities.

MY: What is Hezbollah’s status in the border area, given that at one time the party played a major role in controlling both sides of the border? Have we seen a retreat of Hezbollah on this front?

KK: Hezbollah is currently besieged, with the Lebanese army on one side of the border in Lebanon and members of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham and affiliated groups on the Syrian side. However, the party retains considerable influence in the Beqaa region and across all Shiite villages along the border. Hezbollah’s activities in the border area depend on two main factors: its position within the new political framework of the Lebanese state; and the security and sectarian tensions along the border, which could create a suitable ground for renewed Hezbollah activity. Another important factor is the ongoing Israeli attacks targeting Hezbollah’s activities and assets. Strikes against clans linked to the party will weaken its presence in the border area, while strengthening Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham on the Syrian side.

MY: One fear in Lebanon is that the new leadership in Damascus has Salafi jihadi origins, and that this may have a spillover effect on Lebanon. Do you consider this scenario realistic, and what do you see as the potential risks?

KK: I think this issue will fundamentally reshape the relationship between Lebanon and Syria. There are three main points here: Syria’s new ideology; the defeat of the so-called Axis of Resistance in the region and the ensuing security vacuum; and the potential for sectarian conflict in Lebanon. The ideology of the forces on the ground in Syria today primarily defines itself through the “other.” That is, the Sunni ideology of Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham is a reaction to the Shiite political ideology that has dominated in Iraq, Syria, and Lebanon since the U.S. invasion of Iraq in 2003. Today, the rulers in Damascus are shaping a new Syrian identity, one based on ideological foundations, which expresses itself through phrases such as the description of Syria as “the state of the Umayyads,” or phrases shared on social media such as, “Oh Iran, go crazy, the Sunnis are coming to rule us!” Even Ahmad al-Sharaa, Syria’s de facto president, has entered the fray, speaking of a “natural Syria,” by which he means a Sunni Syria, as opposed to a Shiite Syria.

The Axis of Resistance has left a large security vacuum in Syria after its defeat by Israel in the year after the October 7, 2023 Hamas attack from Gaza. This vacuum has been filled by local jihadi groups, which could provide inspiration to Salafi networks inside Lebanon, enabling them to express themselves from Tripoli to Akkar and the Beqaa Valley. The Salafi movement in Lebanon feels empowered because of the developments in Syria, and its relationship with its Syrian counterparts is likely to strengthen over time. Such a development could create sectarian tensions in Lebanon, with local conflicts undermining civil peace and stability. For example, in the Zahleh region, there are two towns, Taalabaya, which includes Shiites, and Saadnayel, which is Sunni. Celebrations in Saadnayel over Assad’s downfall were characterized by schadenfreude directed against the Shiites of Taalabaya. Posters of Ahmad al-Sharaa on car windows and jihadi songs fill the streets every now and then. Such practices could escalate into armed confrontations across regions of Lebanon.

More generally, religion does not drive politics and what takes place on the ground. However, local identity is already politicized, and as long as the situation in Syria remains unstable, the general mood in Lebanon will be charged and susceptible to mobilization based on perceptions of the self and of the other. This is what we need to watch out for.

Read the full interview here.

In this episode, we highlight the Women Researchers Fellowship, an initiative by the X-Border Local Research Network that supports early-career female researchers in conflict-affected border regions across Asia, MENA, and the Horn of Africa. The fellows share their research, the challenges they face in male-dominated fields, and the new networks they’ve built through the XCEPT programme. Listen as these six distinguished fellows discuss their areas of interest, offer insights into researching in conflict zones, and explore the contributions they aim to make in their fields.

The Research Fellows

Hilina Berhanu Degefa, Ethiopia

Women’s participation in non-state ethnic and ethno-national armed groups in Ethiopia with cross-border implications with Kenya and internal borders.

Htoo Htet Naing, Myanmar

Exploring aspirations and challenges:community perceptions of governance stability and peacebuilding in northern Rakhine states.

Moneera Yassien, Sudan

Use of quantitative methods to analyze the impact of localized conflict on cross-border trade on the Kenya-Uganda border.

Salma Daoudi, Morocco

Complexities of healthcare and impact on security and wellbeing of displaced Syrians on the Turkish-Syria border regions.

Ilyssa Yahmi, Algeria

Smuggling and conflict in the Sahara region in two-fold: Smuggling as a tool for rebel control and governance; and studying the relationship between human smuggling and border securitization.

Faryak Khan, Pakistan

Exploring the peace and conflict nexus in new emerged tribal districts in Pakistan especially in the northwestern border with Afghanistan.

In 2014, the self-styled Islamic State committed genocide against the Yezidi population in Iraq. To mark the anniversary of the genocide, Kings’ College London’s War Studies podcast featured Dr Inna Rudolf speaking with renowned Yezidi human rights advocate Mirza Dinnayi about what life is like for the Yezidi community ten years on from the genocide. Inna and Mirza discuss justice and accountability, the geopolitical situation in the Yezidis’ ancestral homeland, and what still needs to be done to support the community as they deal with a legacy of discrimination that precedes the atrocities of 2014.

This episode is available on Spotify, SoundCloud, and Apple Podcasts,

Sierra Leone’s civil war (1991-2002) was brutal. Reports of ‘savagery’ were not simply displays of rhetoric.[i] Alongside an estimated 75,000 casualties, thousands were subjected to amputations, mutilations, and sexual violence.[ii] Atrocities were committed by all sides, but the amputations carried out by the rebel group Revolutionary United Front (RUF) became emblematic of the suffering inflicted on civilians.

In some cases, the violence of the war was so extreme it seemed to defy reason, but there was one explanation that captured the attention, and the imagination, of the international community: diamonds. A mindless lust for wealth could explain acts of ‘bewildering cruelty’, but a desire for diamonds could also be explained by a ‘rational’ need to finance the war.[iii] The popular link between diamonds and violence is neatly summed up in the 2006 film Blood Diamond, when Jennifer Connelly’s character says, ‘the people back home wouldn’t buy a ring if they knew it cost someone else their hand.’ The reality is, of course, more complex.

Greedy criminals

Given the seemingly inexplicable brutality of the conflict, a prominent school of thought sought to explain the violence by arguing that civil wars were a breakdown of the normal order. As the war began, social, moral, psychological, and political constraints were removed, and, in a ‘vortex of anarchy and lawlessness’, individuals used violence ‘in the service of gratifying their innate human lust for power and material wealth’.[iv] Perpetrators of extreme violence were written off as greedy criminals, who wanted only one thing: wealth. This argument has now been widely discredited. One issue is that it assumes that all those committing violence were inherently greedy, and, as Dr Yusuf Bangura observed, it is also ‘deeply flawed’ to assume ‘rational actions cannot be barbaric’.[v]

If a desire for diamonds motivated acts of atrocity, this could instead be explained by the argument that violence was used strategically as part of a wider campaign of terror to gain, and protect, access to the country’s diamond mining fields. Human Rights Watch reported numerous instances where civilians were abducted and subjected to forced labour in diamond mines, while accounts from the conflict tell of the Sierra Leone Army (SLA) torturing civilians who impeded their access to diamonds.[vi]

Brutality beyond greed

But if greed or economic gain were the cause of the violence, then why were acts committed that went beyond achieving these goals? Some instances of violence were so shocking that it seems unlikely they were motivated solely by a desire to extract the stones.[vii] Even if these fed into a wider strategy of terror, it is hard to believe, as Dr Kieran Mitton argues in his book on the atrocities of the civil war, that this was the main cause of the brutality, rather than ‘the consummatory rewards of violence itself’.[viii]

Status and shame

Feelings of shame amongst the perpetrators could explain why some committed extreme violence. The origins of the civil war have been linked to grievances around uneven development, and a lack of access to education, employment, and resources. Many who joined the RUF, whether voluntarily or by force, were from communities who had been increasingly marginalised. A desire to reverse the status-quo could therefore explain acts of violence committed by teenage fighters against local ‘big men’ and those in positions of power.[ix] Status could also be gained in committing sexual violence; ex-combatants reported that ‘those who participated in rape … were seen to be more courageous, valiant, and brave than their peers’.[x]

Atrocities may also have helped to redress feelings of shame that rebel recruits experienced upon capture when they were subjected to violence and humiliation.[xi] Carrying out dehumanising and degrading acts against others could have been a way for rebels to transfer their own feelings onto their victims. One woman, for example, recounted an experience she and her son endured at the hands of rebels which seemed to serve no purpose other than to humiliate.[xii]

Professor David Keen also argues that extreme violence seems to have been used to eliminate ‘the threat of shame’ in any civilians seen to be embodying it.[xiii] For example, if victims begged for mercy, this could lead to feelings of shame and guilt in the perpetrators. When fighters were faced with pleas for compassion, therefore, this could explain why they responded with further violence, as if they wanted to extinguish the moral judgement they perceived in the cries of their victims. This argument would also explain times onlookers were forced to laugh and clap as atrocities were carried out, as if the perpetrators were compelling approval of their actions.[xiv]

Dehumanisation and disgust

Violence that aimed to reverse or remove feelings of shame could also have been shaped by the emotion of disgust. The RUF claimed from the outset that it was fighting to cleanse society of its ‘rotten’ and corrupt elements, and instances of brutality may have been provoked by a belief among the rebels that their enemies were disgusting and sub-human. Similarly, a belief among the RUF’s enemies that the rebels were beasts and bush devils in turn could explain the use of extreme violence against them.[xv]

But, in the eyes of the perpetrators, the use of gratuitous violence could not only be justified against those seen to be inhuman, it could also be used to render victims sub-human. Amputations and ‘messy’ mutilations, for example, turned victims into ‘the disgusting beings they were supposed to be’.[xvi] There is an argument in the psychology literature that dehumanisation plays more of a role in ‘instrumental’ violence, where the violence is a means to an end, and less in ‘moral’ violence, where the violence can be justified as punishment or retribution.[xvii] By denying victims their humanity, extreme violence was instrumental in two ways. The perpetrators could reinforce the need for violence, and so justify their cause. At the same time, they could also rid themselves of the shame associated with carrying out this violence. Disgust was both a driver and an outcome of atrocities.

Fear

Threading throughout motivations of shame and disgust is the presence of fear: fear of contamination, fear of shame, and fear of moral judgement. Given that so many RUF combatants were forcibly recruited, it is logical to assume fear could in some part explain the cause of atrocities. Testimonies from ex-combatants highlight the role this played in motivating acts of violence.[xviii] Although such accounts could have been given in an attempt to minimise personal responsibility, most RUF combatants did not join voluntarily, and, given the brutalisation process which the group subjected its recruits to, it is clear that violent behaviours were something that had to be taught and enforced.[xix] One boy who was abducted by the RUF aged 15 said ‘when you are captured, you have to change or you become a dead man’.[xx]

Despite the popular link, diamonds on their own do not give a clear-cut explanation for the extreme violence carried out during Sierra Leone’s civil war. Feelings of revenge, fear, disgust, shame, and pride all undoubtedly played a role, while other factors, such as drug use and brutalisation, also deserve attention. To try to explain the atrocities of the civil war is not to try to justify them, but, if we can increase our understanding of what drives people to commit extreme violence, practitioners and policymakers will be better equipped to prevent and address such acts in the future.

[i] Dowden, R. (1995, January 31). Sierra Leone savagery rips nation apart. The Independent. https://www.independent.co.uk/news/sierra-leone-savagery-rips-nation-apart-1570525.html

[ii] Hoffman, D. (2004). The Civilian Target in Sierra Leone and Liberia: Political Power, Military Strategy, and Humanitarian Intervention. African Affairs, 103(411), 211-226. https://doi.org/10.1093/afraf/adh025

[iii] Gberie, L. (2005). A Dirty War in West Africa: The RUF and the Destruction of Sierra Leone. Hurst & Company.

[iv] Mitton, K. (2015). Rebels in a Rotten State. Oxford University Press.

[v] Bangura, Y. (2004). The Political and Cultural Dynamics of the Sierra Leone War: A Critique of Paul Richards. In I. Abdullah (Ed.), Between Democracy and Terror: The Sierra Leone Civil War (pp. 13-40). Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa.

[vi] Human Rights Watch. (2001). World Report 2001: Sierra Leone. Accessed at: https://www.hrw.org/legacy/wr2k1/africa/sierraleone.html; Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Sierra Leone (TRC). (2004). Witness to Truth: Report of the Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Volume 3B). Accessed at: https://www.sierraleonetrc.org/

[vii] Human Rights Watch. (2003, January 16). “We’ll Kill You If You Cry”: Sexual Violence in the Sierra Leone Conflict. Human Rights Watch report 15(1) (A). https://www.hrw.org/report/2003/01/16/well-kill-you-if-you-cry/sexual-violence-sierra-leone-conflict

[viii] Mitton, K. (2015). Rebels in a Rotten State. Oxford University Press.

[ix] Keen, D. (1998). The Economic Functions of Violence in Civil Wars (Special Issue). Adelphi Papers, 38(320), 1-89.

[x] Cohen, D. K. (2013). Female Combatants and the Perpetration of Violence: Wartime Rape in the Sierra Leone Civil War. World Politics, 65(3), 383–415. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0043887113000105

[xi] Mitton, K. (2015). Rebels in a Rotten State. Oxford University Press.

[xii] Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Sierra Leone (TRC). (2004). Witness to Truth: Report of the Sierra Leone Truth and Reconciliation Commission (Volume 3B). Accessed at: https://www.sierraleonetrc.org/

[xiii] Keen, D. (2005). Conflict & Collusion in Sierra Leone. James Currey.

[xiv] Human Rights Watch. (1999, July). Getting Away with Murder, Mutilation, Rape: New Testimony from Sierra Leone. Human Rights Watch report 11(3) (A). https://www.hrw.org/reports/1999/sierra/index.htm

[xv] Mitton, K. (2015). Rebels in a Rotten State. Oxford University Press.

[xvi] Mitton, K. (2015). Rebels in a Rotten State. Oxford University Press.

[xvii] Brudholm, T., & Lang, J. (2021). On hatred and dehumanization. In M. Kronfeldner (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of dehumanization (pp. 341–354). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429492464-chapter22

[xviii] Coulter, C. (2008). Female Fighters in the Sierra Leone War: Challenging the Assumptions? Feminist Review, 88(1), 54–73. https://doi.org/10.1057/palgrave.fr.9400385; Denov, M. S. (2010). Child soldiers: Sierra Leone’s Revolutionary United Front. Cambridge University Press; Gberie, L. (2005). A Dirty War in West Africa: The RUF and the Destruction of Sierra Leone. Hurst & Company.

[xix] Humphreys, M., & Weinstein, J. M. (2004, July). What the Fighters Say: A Survey of Ex-Combatants in Sierra Leone June-August 2003. Accessed at: http://www.columbia.edu/~mh2245/Report1_BW.pdf; Mitton, K. (2015). Rebels in a Rotten State. Oxford University Press.

[xx] Keen, D. (2005). Conflict & Collusion in Sierra Leone. James Currey.

Kheder Khaddour is a nonresident scholar at the Malcolm H. Kerr Carnegie Middle East Center in Beirut. His research centers on civil military relations and local identities in the Levant, with a focus on Syria. Armenak Tokmajyan is also a nonresident scholar at the Middle East Center, focusing on borders and conflict, Syrian refugees, and state-society relations in Syria. Together, they recently published a paper, titled “Borders Without a Nation: Syria, Outside Powers, and Open-Ended Instability,” which was the culmination of several years of work on Syria’s borderlands, with the collaboration of Mohanad Hage Ali, Harith Hasan, and Maha Yahya. Diwan interviewed the two in late September to discuss the impact of Syria’s borders on the country’s conflict and its future.

Michael Young: You have just published a paper at Carnegie titled “Borders Without a Nation: Syria, Outside Powers, and Open-Ended Instability.” What do you argue in the paper, and what are your major conclusions?

Kheder Khaddour and Armenak Tokmajyan: We argue that after more than a decade of war, Syria’s international borders have not only remained intact but have also become more pronounced and reinforced, even as the national framework within those borders has collapsed. If you think about it, much of the Syria we knew before 2011 no longer exists. Many concepts and terms have lost their meaning, or their meaning has changed. One exception is borders, which have become increasingly emphasized and

demarcated, though to varying degrees depending on the specific border. This is largely due to the centrality of borderlands in the evolution of Syria’s conflict, as well as the role played by regional actors who seem to have utilized these international borders as barriers, with the aim of containing Syria’s problems within its territory.

At the same time, despite the endurance of sovereign borders, no new national framework has emerged. While the intensity of war and violence has subsided since 2020, the conflict itself remains unresolved. The containment of Syria’s multilayered grievances within more solid borders may help regional actors to mitigate spillovers, but it won’t resolve the underlying issues in the country. This, in turn, heightens the risk of partial implosions or the collapse of authority from within. We’ve already seen early signs of this across Syria, such as in Suwayda, where the regime’s authority and legitimacy were challenged to an unprecedented degree last year (even more than during the war years), and in Idlib, where Hay’at Tahrir al-Sham, which once appeared firmly in control after a period of stability, faced serious internal fractures.

MY: Your focus on borders underlines that you feel that control over border areas will be an essential feature in defining Syria’s future. Can you unpack this idea for readers?

KK and AT: To understand the evolution of Syria’s armed conflict, one cannot overlook the significance of the country’s borderlands. Numerous actors and factors have come and gone, influencing the trajectory of the conflict, yet the central role of border areas has remained constant—and has even grown in importance. In 2011–2012, rebellion and revolution spread across Syria, but dissent was particularly strong and sustained in its border regions. After the tide turned in2016, the Syrian regime, with the support of its allies, succeeded in pushing many threats toward border areas, but failed to decisively end the civil war by force. Diplomacy also failed to midwife an understanding between Damascus and rebellious border peripheries. As a result, the conflict today remains heavily concentrated in Syria’s borderlands. Any future resolution will not have to deal with international borders, since they are intact, but will have to reimagine the borderlands and their relationships with the much-weakened political center in Damascus.

MY: You point out that demographics, cross-border economic relations, and security have been main drivers of the dynamics in Syria’s border areas. Can you explain what you mean, and what the consequence of this have been?

KK and AT: With the collapse of the national framework, new local-regional links emerged, reshaping security, economic, and demographic dynamics, especially in Syria’s borderlands. This is particularly evident in the northwest, where Turkey’s presence and influence have brought about profound changes on all three levels. However, similar patterns can be observed not only in areas where the regime’s control is absent or contested—such as the northeast and Daraa in the south—but also in border areas with Lebanon and Iraq, where the regime, alongside its allies (notably Hezbollah and pro-Iranian militias), maintains control. While these areas are considered to be under the regime’s authority and do not directly challenge Syrian President Bashar al-Assad’s rule, strong local-regional ties, particularly with Iran, have been developed there, often at the expense of Syria’s sovereignty.

MY: Among the many outside actors in Syria, who do you think is the most consequential, or influential, in the country’s border regions, and why?

KK and AT: Not all foreign actors have the same influence or resources in Syria. However, major change by any one of the actors—notably the United States, Russia, Turkey, or Iran—could be very consequential. These regional and international actors, along with their local allies, are in a delicate equilibrium. Any pronounced shift from one of the key actors could lead to a collapse in the equilibrium among all of them. This prevents any side from making significant advances without disrupting the balance of power, which could allow others to expand their influence. In theory, this situation could shift if any one of the major actors were to significantly alter its policies. However, currently there are no strong indicators this will happen. Yet should it occur, it would certainly create a power vacuum in Syria, potentially triggering a cascade of conflicts until a new status quo is established.

MY: What is the way out of the present impasse? You write that a path to restoring national authority must take place in an “inter-Syrian process” that rests on a “consensus among main regional powers that Syria must remain united, that no one side can be victorious, and that perennial instability threatens the region.” What do you mean by such a process, and is a regional consensus possible given the contenting interests of regional powers in Syria?

KK and AT: This is a delicate question with no clear or easy answer. The way we see it, the primary obstacle to change in Syria is the regime in Damascus. The regime, quite openly, has no interest in discussing a new national framework. It claims to already have one and expects others to forget the war and adopt its vision, which is built on pillars such as personalized rule, autocracy, centralized governance, and economic monopolies—in other words, “Suriya al-Assad,” or “Assad’s Syria.” This approach, and the regime’s central role in the Syrian equation, makes it impossible to begin the search for a new national framework.

Another key point in our analysis is that Bashar al-Assad, and even the broader regime itself, cannot last indefinitely. Despite the regime’s resilience, the road ahead will be challenging, especially if there are internal collapses or a major shift in the balance of power, as discussed earlier. To be sure, these changes could either benefit or weaken the regime. But the key point is that even if Assad manages to navigate these challenges, he is 60 years old and is not immortal. That moment could present an opportunity for a new national framework to emerge, necessarily with active involvement from regional actors. This turning point could potentially shift Syria from its current state of stalemate and crises, both internal and external, toward some form of stability.

Syria remains in a state of civil war, or a form of it. The country’s path to stability will only come through regional and international powers, but the success of this evolution is tied to an inter-Syrian process to create a vision reuniting the Syrian people in a new national framework. This prospect is difficult to imagine in the coming years, but it is also the only means to achieve stability.

This article was originally published by The Conversation on 15 October 2024.

The assassination of Hezbollah’s leader, Hassan Nasrallah, in September sent shock waves through the Middle East and beyond. Nasrallah had evolved into the very embodiment of Hezbollah over his 32 years in charge, and had established himself as a key figure in Iran’s so-called axis of resistance.

At the height of his influence, Nasrallah was so widely admired from North Africa to Iran that shops sold DVDs of his speeches, cars were embellished with his image, and many Lebanese even used his quotes as ringtones.

He is not the first sectarian leader to have been assassinated in Lebanon. And on each occasion the killings have intensified sectarian tensions in the country and have jeopardised social stability. The impact of Nasrallah’s death will, in my opinion, probably be no different.

His killing could destabilise the fragile balance of power in the country. And it could also trigger a reshuffling of political alliances within Lebanon’s complex sectarian power-sharing framework that was established in 1990 after the end of the civil war.

A man in Baghdad, Iraq, carries an image of the late Hezbollah leader, Hassan Nasrallah. Ahmed Jalil / EPA

In 1977, the leftist leader of the Druze community, Kamal Jumblatt, was assassinated by two unidentified gunmen in his stronghold in the Shouf mountains of central Lebanon. Many of his followers believed they knew who was responsible, and channelled their anger toward Lebanon’s Christian community.

Security officials reported that more than 250 Christians were killed in revenge, many brutally, with their throats cut by Druze assailants. At least 7,000 Christians fled their villages after the killings, with around 700 of them travelling to the presidential palace in Baabda, a suburb of Beirut, to request government protection.

This spell of fighting marked a significant escalation of sectarian violence during the civil war, and resulted in a persistent cycle of retaliation, deepening division and entrenched sectarian identities.

Then, in June 1982, a powerful bomb explosion killed Lebanon’s Maronite Christian president, Bashir Gemayel. The assassination was carried out by two members of the Syrian Social Nationalist party, reportedly under orders from Syria’s then president, Hafez al-Assad.

The next day, Israeli troops entered west Beirut in support of the Phalange, a Lebanese Christian militia that blamed the Palestinian Liberation Organisation (PLO) for Gemayel’s death. Israel had earlier that month launched a massive invasion of Lebanon to destroy the PLO, which had been carrying out attacks on Israel from southern Lebanon.

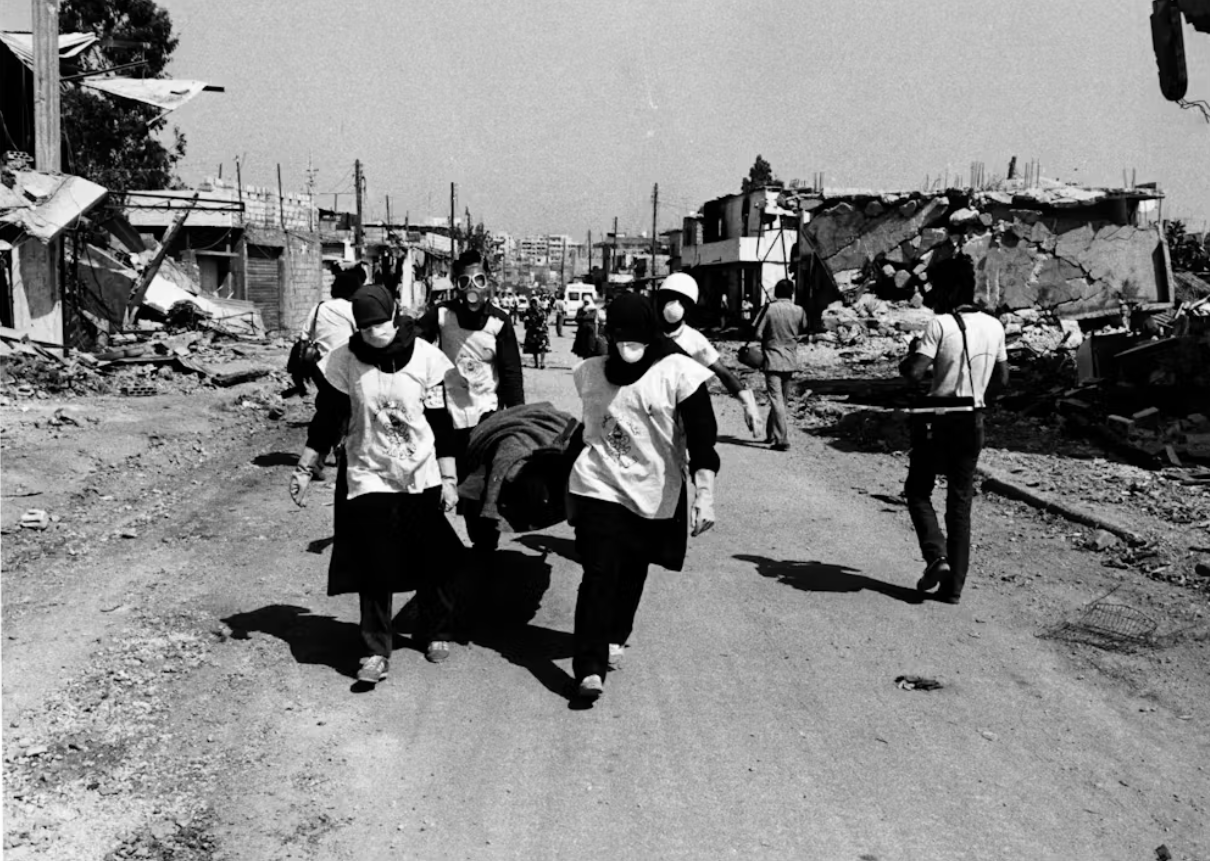

Knowing that the Phalangists sought revenge for Gemayel’s death, Israeli forces allowed them to enter the Shatila refugee camp and the adjacent Sabra neighbourhood in Beirut and carry out a massacre a few months later. Lebanese Christian militiamen, in coordination with the Israeli army, killed between 2,000 and 3,500 Palestinian refugees and Muslim Lebanese civilians in just two days.

Scores of witness and survivor accounts say women were routinely raped, and some victims were buried alive or shot in front of their families. Women and children were crammed into trucks and taken to unknown destinations. These people were never seen again.

UN relief workers at the Shatila refugee camp in the aftermath of the massacre. Keystone Press / Alamy Stock Photo

Following the end of Lebanon’s civil war, there was a period of relative stability as a delicate balance of power was established between Lebanese sects. But a car bomb in downtown Beirut in 2005 killed the country’s former prime minister, Rafic Hariri, and again altered the dynamics of sectarian rivalry in Lebanon.

Lebanon lost one of its central figures, while fury over Syria’s alleged involvement in Hariri’s murder raised international pressure on Syria to end its 29-year occupation. The withdrawal diminished Syria’s influence as the primary mediator in the country, and the underlying tension between the two main sectarian groups vying for power, the Sunnis and Shia, surfaced abruptly.

Lebanon experienced 18 months of political deadlock and protests, with Hezbollah and its allies pushing for a veto power in the government. Hostilities intensified and violence became a constant threat.

Then, in May 2008, the Lebanese government attempted to remove a Hezbollah-aligned security officer and investigate the organisation’s private communications network. This ignited fierce clashes between supporters of the government and the Hezbollah-led opposition.

Hezbollah and its allies occupied west Beirut and at least 71 people, including 14 civilians, were killed over the following fortnight.

Hezbollah steadily expanded and enhanced its military capabilities over the next ten years. And it also emerged as a powerful regional player by joining Iran and Russia in supporting Bashar al-Assad’s regime in the Syrian civil war.

The organisation assumed an increasingly central role in Lebanese politics, and secured a majority of seats in the 2018 parliamentary elections.

Lebanon’s modern history is rife with conflict. The assassination of Nasrallah marks the latest in a series of bloody milestones that have served as sharp turning points – and even transformational moments – in Lebanon’s sectarian politics.

Christian and Sunni factions in Lebanon have for years viewed Hezbollah as effectively commandeering the state, leveraging its powerful military wing and Iranian backing. With Hezbollah now visibly weakened in the absence of its powerful and charismatic leader, this longstanding power dynamic may be set for a shift.

There are signs that divisions are already deepening. Videos from Tripoli, a predominantly Sunni city in northern Lebanon, show residents dancing in the streets in celebration of Nasrallah’s death. Other videos show people removing Hezbollah stickers from the vehicles of displaced Shias.

Meanwhile, Hezbollah supporters have pledged retaliation for Nasrallah’s elimination. Lebanon once again finds itself on the verge of fierce sectarian tension and instability.

This article was produced with support from the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research programme, funded by UK International Development. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

Despite an end to the active conflict in the Tigray region, Ethiopia’s political and security crisis is deepening. Much of the country’s insecurity is linked to competition over natural resources, which has fuelled land disputes and intensified cross-border smuggling, driven inter-communal conflict, and aggravated environmental hazards.

Ethiopia has substantial gold reserves, particularly in the areas bordering Sudan. These reserves made up more than 95 per cent of the country’s $428 million in mineral exports between 2023–24. Ethiopia officially exported a high of 12 metric tonnes of gold between 2011–12, a figure that fell to 4.2 tonnes in 2023–24, despite the emergence of new gold projects and the expansion of artisanal, or small-scale, mining.

Gold mining is increasingly informal and outside of federal government control. Several large-scale gold projects have been ‘in the pipeline’ for over a decade without starting official production. Some have been overtaken by illegal exploration, extraction and smuggling operations, often in collusion with various government and non-government actors.

Gold mining in Ethiopia is increasingly informal and outside of federal government control.

Confidential reports suggest that some foreign investors and Ethiopian geologists possess more detailed mining data than the government. Artisanal mining employs at least 1.5 million people (74 per cent of miners) and accounts for 65 per cent of mining foreign exchange earnings.

Of Ethiopia’s regions, Tigray leads the way in exploration and commercial licensing, with over 90 licensed gold mining companies. Tigray was among the biggest suppliers of gold to the National Bank of Ethiopia before the war, with about 26 quintals (2.6 metric tonnes) of gold annually, valued at around $100 million. Since the Tigray war, much of the region’s gold has instead been smuggled – with estimates that nationally, this amounts to as much as 6 tonnes of gold annually, significantly more than current official exports.

Multiple non-state actors, including leaders of the Tigray Defense Forces (TDF), foreign nationals, and local businesspeople are involved. Control over gold has been one of the reasons impacting the recent internal split within the leadership of the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the dominant party in the region.

Reports suggest that TDF leaders and some members of the TPLF oversee most of the illicit mining, with gold smuggled out of Ethiopia through Sudan, to the UAE. This plunder of gold ultimately harms the Tigrayan public, as the resource should be used to rebuild the region destroyed by a devastating war. Equally worrying, the gold rush in Tigray is becoming increasingly violent. A recent conflict in a Rahwa gold mine in northwestern Tigray resulted in over 20 deaths.

Other conflict-prone regions are also seeing an expansion of the illicit gold sector, with Benishangul and Oromia regions ‘officially’ barely producing a quarter of the amounts projected by the government. A Canadian company agreed to invest $500m over 15 years in exploiting gold reserves around the small town of Kurmuk in Benishangul, along the Sudanese border. But encroachment by illicit miners has prevented access to the site, and the involvement of regional officials and local militants has left the federal government unable to act. There are reports of massive extraction taking place, with gold again being smuggled out via Sudan to the UAE.

Keen to prevent the loss of hundreds of millions of dollars every year, the Ethiopian government is trying to curb illegal mining. Cracking down on the illicit market, incentivizing legal suppliers, and amending restrictive and ambiguous laws are measures the government is taking.

However, contested authority between federal, regional and local administrations has paved the way for opportunistic, nepotistic, and criminal elements to profit, which fuels armed conflict. As such, the federal government’s ability to impose peace and security is uncertain at best.

These state and non-state elites also cooperate and compete for power in transnational spaces. Sudan is the primary recipient of illicit gold from Ethiopia due to its proximity to Ethiopia’s gold belt. Illicit gold from Benishangul, Gambela, Oromia, Tigray and parts of southern Ethiopia flows into Sudan via a porous border with the help of smugglers and brokers, facilitated by conflict in Ethiopia’s Tigray region and in Sudan.

The illicit gold networks in Sudan have flourished in its war economy. Profits generated by the smuggling of gold sustain the war efforts of armed actors.

Other smuggling routes traverse Afar to Eritrea and Somaliland, and the Guji area near the Kenyan border. Regional airports have also become transit points for illicit gold, which is sent to destinations like Uganda and then re-exported to the UAE.

The illicit gold networks in Sudan have flourished in its war economy. Profits generated by the smuggling of gold from and through Ethiopia, Eritrea, Uganda and as far as the DRC, alongside domestic Sudanese production, sustain the war efforts of armed actors, notably the Sudanese Armed Forces and Rapid Support Forces.

But it is the UAE that is the ultimate destination for much of Africa’s smuggled gold, including Ethiopia’s. According to a recent report by Swiss Aid, 2,569 metric tonnes of undeclared gold from Africa, worth a staggering $115 billion, ended up there between 2012 and 2022. The UAE’s questionable import procedures, which do not necessarily require detailed information about the origins of gold, as well as incentives to import ‘scrap’ gold, make it ideal for smugglers.

The expansion of illicit gold mining is exacerbating Ethiopia’s complex conflicts. Regional states have reclaimed mining concessions to assert control amid diminishing federal influence. At the same time non-state armed actors are competing for gold revenues to expand their local authority and, in some cases, challenge the authority of the state. The gold sector is becoming increasingly fragmented and militarized, and risks being drawn into multiple local and ethnic fractures as the federal government struggles to impose the rule of law.

But in addition to tackling issues at the national level, addressing this issue in the long term requires a better understanding of the transnational nature of gold flows across the region, and how these interconnections form part of a conflict ecosystem that operates across borders.

The UAE is both the prime customer for Ethiopia’s stolen resources and one of its most valued diplomatic partners, offering external support that is as valuable as gold to a government under enormous pressure. The UAE’s emergence as both patron and consumer of conflict gold is a contradiction that Ethiopian policymakers and international partners who support sustainable peace in the region will need to resolve if progress is to be made.

This article was produced with support from the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research programme, funded by UK International Development. The views expressed do not necessarily reflect the UK government’s official policies.

In Mosul, Iraq, efforts are underway to help the city move forward after decades of violent conflict and devastation under the rule of Saddam Hussein, the US occupation, and the brutal reign of Islamic State (IS).

One initiative which was created to support the city’s recovery was a community tree-planting project called Green Mosul. Green Mosul was developed by the Mosul Eye organisation with a dual objective to raise awareness of the climate crisis and to unite diverse communities after years of division and conflict.

The Green Mosul project was launched in 2022 with the goal of planting trees across the region, and Mosul Eye sought to involve the local population from the outset. If different parts of society could work together on the shared goal of making the city green, it was hoped that this would facilitate communication between divided communities, as well as offer them a chance to disconnect from the social and religious problems of the city.

The project made a concerted effort to choose religious and cultural sites to plant trees in. In this way, these places were turned into green public areas that could be enjoyed by all Mosulis, encouraging the pubic to see these heritage sites as shared spaces and not just for those from a particular community.

The planting of trees in cultural and religious sites also had another aim. Omar Mohammed, the founder of Mosul Eye, hoped that Mosulis would see that Mosul’s heritage was not just buildings, but the trees and the green spaces around them – and that this heritage needed to be protected too. When IS took control of Mosul, the city suffered an enormous amount of loss and devastation. The terrorist group might not come back but, if the climate crisis isn’t addressed, Mosul could face destruction of a different kind.

Mosul, historically known as the city of two springs due to its temperate autumn, is directly impacted by the climate crisis. The city now experiences longer and more intense heatwaves, reduced water flow, and an increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events, such as droughts and floods. This not only risks the health of the city’s population, but has profound socio-economic implications. Agriculture in the region relies on predictable weather patterns. With changes in rainfall and temperature come rising food prices, higher poverty levels, and increased migration as people move away from rural areas to seek better living conditions.

On top of this, Mosul’s rich cultural heritage is at risk, as extreme weather events and changing environmental conditions can accelerate the deterioration of its many historic buildings and archaeological sites.

Mohammed believes that trees offered an ideal entry point for introducing environmental education to Mosul. Trees symbolise life and renewal, but they also play a key role in mitigating the climate crisis. To start the conversation on the climate crisis, Mohammed organised workshops and community meetings alongside the planting of trees, which encouraged locals to engage in discussions about trees, the climate crisis, and the effects of both on the local environment.

For Mohammed, it was important to make sure the impact of the climate crisis was discussed in a locally meaningful context. After years of conflict and destruction, the focus for most Mosulis was on restoring their livelihoods and rebuilding their lives, and Mohammed knew that many people wouldn’t engage with global narratives on the climate crisis while they had more immediate problems to deal with.

For example, when several neighbourhoods in the Al-Jadidae area of Mosul were experiencing water shortages, Green Mosul engaged the community in discussions about how the climate crisis impacts water availability and agricultural productivity and the need for sustainable water management practices.

In Mosul’s Old City, Green Mosul encouraged residents to consider the climate crisis and the importance of green spaces as they rebuilt their homes. The Old City had suffered immense destruction under IS’ reign, and the extensive use of heavy building machinery in reconstruction efforts was exacerbating the already-poor air quality. One resident, inspired by the project, transformed a narrow alley near his home in the Dakkah Barakah neighbourhood into a vibrant green space.

Green Mosul also arranged tree-planting events with local schools, businesses, and organisations in the hope this would foster collective action and introduce a sense of ownership and responsibility towards the environment. One participant, Anas, remarked that ‘planting these trees made me realise my role in combating the climate crisis. I am now more conscious of my daily actions and their environmental impact.’

As the city visibly turned greener, Green Mosul was able to attract the interest of both the public and the media, and to raise awareness of the need for sustainable practices and long-term strategies to safeguard the environment.

Through the planting of trees, Mosul Eye also found a language for the first time to speak to people about their areas without having to speak about sectarianism.

In Tel Skuf, 28km north of Mosul, the park in front of Mar Gorgis Church was transformed, thanks to Green Mosul, into a communal space that encouraged interaction and unity among different groups. In this instance, the need for more green areas became a bridge that allowed communities to engage across other divides and overcome tensions that had previously separated them.

In Bashiqa, another beneficiary of the Green Mosul project, farmers from different religious backgrounds came together to share knowledge about sustainable farming practices and crop rotation techniques, collaborating on a community garden project that utilised ancient irrigation methods to conserve water and increase crop yields. This practical co-operation resulted in improved agricultural output and strengthened inter-communal relationships.

In many places across the region, collaboration triumphed over division. In programme activities, conversations about Tal Afar no longer focused on Sunnis and Shia, but on the water springs and the green areas. When people spoke about Sinjar, they no longer talked about Muslims and Yezidis, but of the mountains and their importance. Discussions around the Nineveh Plains centred not on Christians and Muslims, but farming and green spaces.

The Green Mosul project ended in March 2023, but the universities and the local government have committed to continuing to plant trees, and Mosul Eye is still working to facilitate discussions on the climate crisis. The organisation knows that addressing the issue not only provides an opportunity to support post-conflict reconciliation in a divided city, but it also helps to protect the city’s future.

Mohammed has recently convinced the University of Mosul’s Central Library to create a section on the climate crisis, and he is currently working with schools to get the topic of the climate crisis included in the curriculum. Although this initiative may take time, it is a crucial step towards embedding the climate crisis education from an early age and instilling hope and optimism about the future.

The project has also empowered individuals to take steps of their own. Ahmed, a citizen of Mosul and a volunteer with Green Mosul, has initiated advocacy efforts within his community to promote recycling and revitalisation of green spaces in Mosul. Abdulrahman, an agricultural engineer hired by Mosul Eye to conduct a study on soil health in Mosul, was so shocked by the extent of the city’s environmental damage that he has taken it upon himself to increase awareness about this problem in the academic community. In response to these efforts, the University of Mosul has been more proactive in integrating studies focused on the climate crisis in Mosul into its curriculum.

Through Green Mosul, Mosul Eye also successfully arranged the first international conference on the climate crisis in Mosul. For the first time, amidst the city’s ruins, people engaged in discussions about the climate crisis. Mohammed hopes that Mosul will become part of the global discourse on the climate crisis because, if Mosulis see that someone around the world is talking about the climate crisis in their city, they might be inspired to take the initiative themselves. He also hopes that they will set an example to other activists: if the people of Mosul, in the midst of destruction, can still discuss and tackle the climate crisis, then it should be possible anywhere.

Find out more about Green Mosul in this interview with Dr Omar Mohammed, for the XCEPT research project at King’s College London.

Over the past decade, the number and intensity of both inter- and intrastate conflicts has been rising. In 2022, mostly due to Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the war between the Government of Ethiopia and the Tigray People’s Liberation Front (TPLF), the number of battle-related deaths from interstate conflicts reached its highest number since 1984.[i] According to the Armed Conflict Location and Event Data Project (ACLED), in the first month of 2024, one in six people around the world were estimated to have been exposed to conflict.[ii]

Human history, and our present, is rife with conflict, but researchers are still short of comprehensive theories that could explain the common ‘logic’ of conflicts across specific contexts. Why do people enter into conflict in situations when they could agree a peaceful settlement instead? The dynamics of conflict are incredibly complex and depend on countless, constantly evolving factors, from the environment to the unique individuals comprising the groups. This creates a serious challenge for predicting the emergence of conflict and its consequences. Models offer a means to consider various elements in parallel, untangling the complexity of conflict dynamics.

Models are sets of formulas developed by researchers to describe how different factors interact, integrating abstract theories to give a simplified, testable representation of real-life conflict. As the study of conflict is multidisciplinary, models provide a common language for researchers working in disparate fields, from political science to evolutionary biology. This is important as it allows for conflict analysis to integrate findings from different academic disciplines, and this can uncover new insights.

In one example, a model analysing strategic incentives for mass killings brought together several existing theories which yielded new, and somewhat unexpected, results: namely that constraints on the magnitude of mass killings, such as third-party intervention, may actually increase their probability under certain conditions.[iii] Models can also inspire further research by providing predictions that must then be tested against data collected from real conflicts.

A prototypical model of conflict is a simple ‘bargaining game’. In this model, two groups or individuals negotiate how to distribute something of value, which results in either a peaceful resolution or fighting. If fighting takes place, this item of value, be it a material or symbolic resource, is divided according to the outcomes of the conflict, but some of its value is destroyed, rendering aggression inefficient and collectively undesirable. Conflict dynamics are rarely that straightforward, and this model makes certain assumptions, such as theorising that groups are made up of members who have the same characteristics and who all act in the same way. Nevertheless, this still provides a useful base from which to generate testable hypotheses.

While models simplify various elements of conflict, they are beginning to take more detail into account. An example of this is the consideration of group heterogeneity. Groups in a conflict are not homogenous units, but are instead made up of individual agents with different motivations, identities, classes, behaviours, and more. Including these differences in models can significantly influence their predictions.

One facet of this heterogeneity is the difference in social classes within a population. A series of models by economists Esteban and Ray predicted that conflict was more likely to occur if religious or ethnic factions contained members from a mix of economic classes.[iv] An explanation for this is that conflict requires financing from the rich and fighting from the poor. Greater inequality also decreases the opportunity cost for both sides. It costs the rich less to fund the conflict, while, in the absence of other opportunities for income, fighting becomes the best option for potential gains for the poor.

Real-world data supported this prediction, finding that civil wars between groups with greater levels of internal economic inequality have been more severe in terms of death tolls and the length of the conflict.[v] This is just one example, but recent work has begun to make more nuanced predictions.[vi]

Models of conflict move us beyond stories to explanations. They allow us to consider how various elements interact side by side, and they help researchers from different fields to operate under a shared understanding. Work in this direction has already been generating increasingly complex models of conflict, and this will continue in the future as models take further nuances into account. Models offer an exciting avenue for exploring new ideas and will be instrumental in informing our understanding of conflict dynamics.

[i] Obermeier, A.M. & Rustad, S.A. (2023) Conflict Trends: A Global Overview, 1946–2022. PRIO Paper. Oslo: PRIO.

[ii] https://acleddata.com/conflict-index/

[iii] Esteban, J., Morelli, M., Rohner, D.: Strategic mass killings. Journal of Political Economy 123(5), 1087–1132 (2015) https://doi.org/10.1086/682584

[iv] Esteban, J., Ray, D.: Conflict and distribution. Journal of Economic Theory 87(2), 379–415 (1999) https://doi.org/10.1006/jeth.1999.2549; Esteban, J., Ray, D.: On the salience of ethnic conflict. American Economic Review 98(5), 2185–2202 (2008) https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.98.5.2185; Esteban, J., Ray, D.: A model of ethnic conflict. Journal of the European Economic Association 9(3), 496–521 (2011) https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1542-4774. 2010.01016.x; Esteban, J., Ray, D.: Linking conflict to inequality and polarization. American Economic Review 101(4), 1345–1374 (2011) https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.101.4.1345.

[v] Esteban, J., Mayoral, L., Ray, D.: Ethnicity and conflict: An empirical study. American Economic Review 102(4), 1310–1342 (2012) https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.102.4.1310

[vi] Rusch, H. (2023). The logic of human intergroup conflict: Knowns and known unknowns. Maastricht University, Graduate School of Business and Economics. GSBE Research Memoranda No. 014 https://doi.org/10.26481/umagsb.2023014

Nils Mallock is a postdoctoral researcher with the Cross-Border Conflict Evidence, Policy and Trends (XCEPT) research programme at King’s College London (KCL). Here, he tells us about his experience researching the psychological causes of violent and high-risk political action, touching on his previous work in Iraq and Lebanon.

I’m Nils Mallock, a postdoctoral researcher for the XCEPT team at KCL. My research focus has mostly been in political violence and extremism, and how this differs from more moderate forms of collective action, such as activism and peaceful political protest. Specifically, I have looked at the psychological causes underlying political behaviour, asking what motivates people to engage in, or disengage from, different forms of political action in different contexts.

Within the XCEPT project, I am working on our large longitudinal survey, called the Impact of Trauma Survey (IoTS), in Lebanon and Iraq. The IoTS is exploring the psychological impact of conflict exposure on things like mental health, trauma, and people’s perceptions of their social environment, and how these factors then in turn shape a person’s political beliefs and behaviours. As well as this, I’m jointly responsible for leading a multifaceted intervention study that we’re planning in Iraq, where we will test psychological interventions that could encourage reconciliation between groups in a post-conflict context.

The Al-Shohada Bridge in Mosul, Iraq, which was destroyed during ISIS’ occupation of the city. Credit: Nils Mallock

After finishing my undergraduate studies in Germany, I moved to Lebanon to work as a researcher for the Konrad Adenauer Foundation’s Syria/Iraq office, as I was learning Arabic and interested in the dynamic politics of the Middle East. Seeing the effects of conflict first-hand made me want to understand how these conflicts emerge and what drives people to participate in them. I realised that everyone talks about political conflicts at a very structural and abstract level, looking at group dynamics, demographic changes, and social movements, but that this does not really explain why, among people in the same environment, some people embrace political violence, others embrace activism, and the vast majority do not even engage at all. There are clearly individual factors at play, but we don’t understand them robustly, especially in harder-to-access places, such as in conflict-affected regions, where insights are probably most valuable.

A display of art-based cultural and political action in Jenin Refugee Camp, West Bank. Credit: Nils Mallock

This interest led me to my PhD with the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE), which examines the psychological motivations for violent versus peaceful political action in what I call ‘high-stakes’ environments. This can mean conflict-affected contexts, but also could be in countries with authoritarian governance. These high-stakes environments make it drastically more risky or costly for individuals to take even peaceful political action. I’m interested in what causes people to overcome these (seemingly) rational barriers and engage, especially for more radical and extreme political actions. This means asking: what psychological motivations are strong enough for people to ignore these costs and risks?

My PhD investigates this through quantitative studies in Iraq, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, and the Palestinian Territories, supplemented by interviews with activists and members of armed groups. For example, one study examined the effect of geographical proximity to Israeli settlements in the West Bank on different forms of protest behaviour. This study found that the mere presence of these settlements caused a shift towards participation in higher-risk action and away from lower-risk forms of protest.1

Silwan district in East Jerusalem. The predominantly Palestinian community is the site of intense land disputes, forced evictions and construction of Israeli settlements. Credit: Nils Mallock

I’m currently working on an XCEPT article, joint with my PhD at LSE, in which we report a series of experimental studies that I conducted in collaboration with civil society organisations and universities across seven locations in Iraq. These explored the role of uncertainty on political radicalism and activism. Previous studies have shown that, when someone’s sense of self is threatened, this creates feelings of uncertainty which often leads the person to act defensively. Interestingly, this defensiveness can manifest in expressing stronger opinions and extreme views about things that are completely unrelated.

For instance, if I lose my job, and that is central to my identity, I may try to compensate for that by expressing more extreme political opinions on controversial issues like abortion rights or discrimination against other groups, because this provides a feeling of certainty about my world view and restores a sense of unique identity. However, it wasn’t known at the time whether this mechanism extended also to intentions to actually act on those political beliefs. On top of that, we didn’t know whether this applied in conflict-affected settings, where uncertainty is generally higher.

View onto Mohammad Al-Amin Mosque in Beirut, Lebanon. Credit: Nils Mallock

In our studies, participants were exposed to feelings of uncertainty, through an exercise in which they reflected on their own mortality. Their intentions to take different kinds of political action were then measured. What we found is that the people exposed to feelings of uncertainty were more willing to engage in political action, and especially in radical actions compared to more moderate activism. However, this was not the case when the participants were given another opportunity to restore their self-certainty – by reflecting on and writing a short text about something particularly meaningful to them – before measuring their intentions. Interestingly, we found some evidence that those measuring higher in emotional stability were in general not responding to those mechanisms. These findings could give some initial insights to help design targeted psychological interventions to support social reconstruction efforts in conflict-affected regions.

Street advocacy by Palestinian activists in South Hebron Hills, West Bank. Credit: Nils Mallock

My colleagues and I on the XCEPT project are going to conduct a comprehensive study in Iraq to understand causal mechanisms of intergroup conflict and, as importantly, pathways for reconciliation and peacebuilding between former or current conflict groups. Intervention studies have already been done in other complex settings, such as in the Israel-Palestinian conflict, but this kind of research is actually rare in Iraq. This is partly because it’s harder to access as a research population, especially with surveys of this scale.

What we will do is test several psychological interventions promoting reconciliation between groups, working with local partners and civil society organisations. For example, one intervention will aim to counter false perceptions of the outgroup as being ‘fixed’ and inherently incapable of change, which can be an obstacle for successful reconciliation. Then we will compare the different interventions in what’s called a ‘tournament’ study design, where the most successful intervention from this stage will be taken forward with participants from all over Iraq, including many of those taking part in our IoTS.

Banners in South Lebanon displaying members of political parties and militias. Credit: Nils Mallock

This will allow us to look at how different characteristics identified in our IoTS, such as mental health or personality traits, influence responses to the intervention. We will also target these interventions to their specific context within Iraq by working with local experts and advisors to make sure the materials are relevant to the different groups, and this will be interesting because it’s quite novel to do this kind of work.

The intervention study will be highly innovative research pushing into new territory. This is because it is being run in Iraq, which is rare, and because it will directly compare multiple interventions on a large-scale with a highly diverse sample. The overall goal is to identify causal mechanisms of conflict reconciliation and the improvement of intergroup relations. The big benefit of this study is that it involves measuring the intentions of the participant before and after the intervention. This will help practitioners, who are signalling strong demand for insights into what efforts might be effective to build social cohesion in a post-conflict setting.

This Q&A was originally published on the ICSR website.