They are a group of Lebanese muscular tattooed men dressed in uniform black t-shirts, some of them heavily bearded, and carrying provocative religious iconography and symbols.[i] They are not Muslims, but Christians. They call themselves Jnoud al-Rab (Soldiers of God) and lead their own political, religious, and spiritual uprising, guided by the word of Jesus Christ as they interpret it.[ii] Their coat of arms is shown on their cars, mopeds, and t-shirts: a picture of the wings of Saint Michael the Archangel and a shield decorated with the cross of Jesus Christ, all sitting above the Holy Bible.[iii]

Soldiers of God claims that it carries out the teachings of Jesus Christ and is entrusted with his commandments. It defines itself as neither a party nor an organisation, but a militia group formed with the aim of protecting Christians and offering reassurances to residents worried about rising levels of crime – including armed robberies, carjackings, handbag snatches, and the theft of internet and telephone cables – in the majority Christian neighbourhood of Achrafieh in Beirut.[iv]

Self-security in Beirut is already a concern as Hezbollah conducts security patrols, checks the identities of passing citizens, interferes in the movements of the Lebanese security services, and blocks journalists from moving freely in the areas under its control.[v] The rise of far-right Soldiers of God has raised fears that Achrafieh will join this self-securitisation and paramilitary policing phenomenon, bringing Beirut back to the time of the Lebanese civil war (1975-1990) when the state collapsed, militants controlled the streets, and the city was ideologically divided into the Christian East and Muslim West. These fears are increasing in light of the ongoing political paralysis and economic depression that has afflicted Lebanon since 2019, which crippled the state apparatus and is fuelling poverty in the worst shock since the civil war.[vi]

Read the full article here, originally published on the ICSR website.

[i] L’orient Today (2022) Who are Achrafieh’s Soldiers of God? [Online] available from https://today.lorientlejour.com/article/1304447/who-are-ashrafiehs-soldiers-of-god.html

[ii] Soldiers of God (2023) [Facebook] 25 July 2023. Available at https://www.facebook.com/photo/?fbid=670093338494283&set=a.628163606020590

[iii] Ibid.

[iv] Jnoud El Rab (2023) About Us [online] available at https://www.jnoudelrab.com/about-us/;

Reuters (2022) Beirut neighbourhood watch echoes troubled past [online] available at https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/beirut-neighbourhood-watch-echoes-troubled-past-2022-11-27/

[v] AlHurra (2022) The Eyes of Achrafieh… guardian angels or an introduction to self-security and division in Beirut? Translated by El Kari, Mohamad. [Online] available at https://bit.ly/3wysNVf

[vi] Ibid.

Dr Nafees Hamid interviews Dr Hannes Rusch about his work examining the ‘logic’ of intergroup conflict.

Dr Rusch talks us through the basic models which explain why groups might choose conflict, and highlights key questions that remain unanswered by the research.

You can also listen to the King’s College London War Studies podcast on their platform, where this episode was originally published.

In this episode, Dr Costanza Torre and Dr Fiona McEwen discuss XCEPT’s research in South Sudan, which aims to understand how experiences of conflict may lead someone to engage in violent, instead of peaceful, behaviour. They discuss the importance of hiring local researchers, the challenges of carrying out research in South Sudan, and how mental health disorders may be understood differently in South Sudan.

*This episode was recorded in early March 2024, before the recent escalation of violence in Sudan.

‘Resilience’ has become a buzzword in the field of countering violent extremism (CVE), but how useful is it?

In this episode, Federica Calissano interviews Dr Nafees Hamid about the benefits and drawbacks of CVE initiatives which focus on building resilience to violent extremism.

You can also listen on the King’s College London War Studies podcast channel, where this episode was originally published.

Read Federica’s XCEPT blog post: What do we mean when we talk about ‘resilience’ to violent extremism?

In recent years, numerous citizens of the KRI have lost their lives trying to cross the English Channel in small boats. Many people moving from the region to Europe and the UK since 2014 have done so in response to corruption and political conflict in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI). Since its creation in 1991 with the support of the US and the UK, the KRI has been under tight control of two main parties: the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (PUK) and the Kurdistan Democratic Party (KDP). Ruling the region through a duopoly, the PUK/KDP have provided little power, resources and economic opportunities to citizens who fall outside their own clientelist and patronage networks.

Party dominance and corruption, combined with years of conflict over resource-sharing with the central government in Baghdad, have compounded the KRI’s financial and economic crisis and generated strong incentives for the region’s citizens to migrate using available smuggling networks. The KRI is riddled with active smuggling networks that make it possible for citizens from the region to invest their entire life savings in the hope of relocating to the UK to begin anew, highlighting the deep-seated desire for change and a better life away from the systemic issues plaguing their homeland.

Chatham House XCEPT research highlights the involvement of both local and international actors in a complex web of human smuggling, which capitalizes on the desperation of individuals seeking better lives. This transnational network exacerbates the plight of its victims, exploiting their circumstances for profit. The recent arrests have once again brought to light the issue of Kurdish migration, which for years has been driven by political corruption and conflict within the KRI, facilitated by transnational networks.

Read the full blog here, originally published on the Chatham House website.

I just came back from the 2024 Stockholm Forum on Peace and Development hosted by SIPRI. It was a stimulating event, replete with doom and data, attended by a throng of practitioners, activists and researchers, many doing remarkable things to put our fractured world to rights.

I was there with Simon Long’oli, Director of the Karamoja Development Forum, a community organisation in northern Uganda, where violence is an everyday reality. Simon and I were there to provoke colleagues on their notions of what constitutes good evidence in situations of violence and conflict.

We were arguing that community action research offers not only deep insight but also reaches the parts other research doesn’t reach. We were being cheeky, because we know that good qualitative and quantitative research has the capacity to be pivotal too. Nonetheless, in our experience, traditional research often does little to bring the community onside. What’s missing is research that systematises the knowledge and political energy of the people who suffer the violence.

Take Roger Mac Ginty’s idea of ‘everyday peace’. It’s not less important because it’s every day, but more important because it’s the way in which situations of peace or insecurity come into being. If people’s efforts to make life safe and productive are well enough organised and powerful enough, then the place and people will be at peace. If they are constantly thwarted, then their distrust of the authorities and politicians will put them on the defensive – every day. More foot soldiers, more crime, more despair.

At least that is what Simon and his community colleagues found when they led community action research on the Uganda-Kenya border.

To read the full blog, visit the IDS website, where this was originally published.

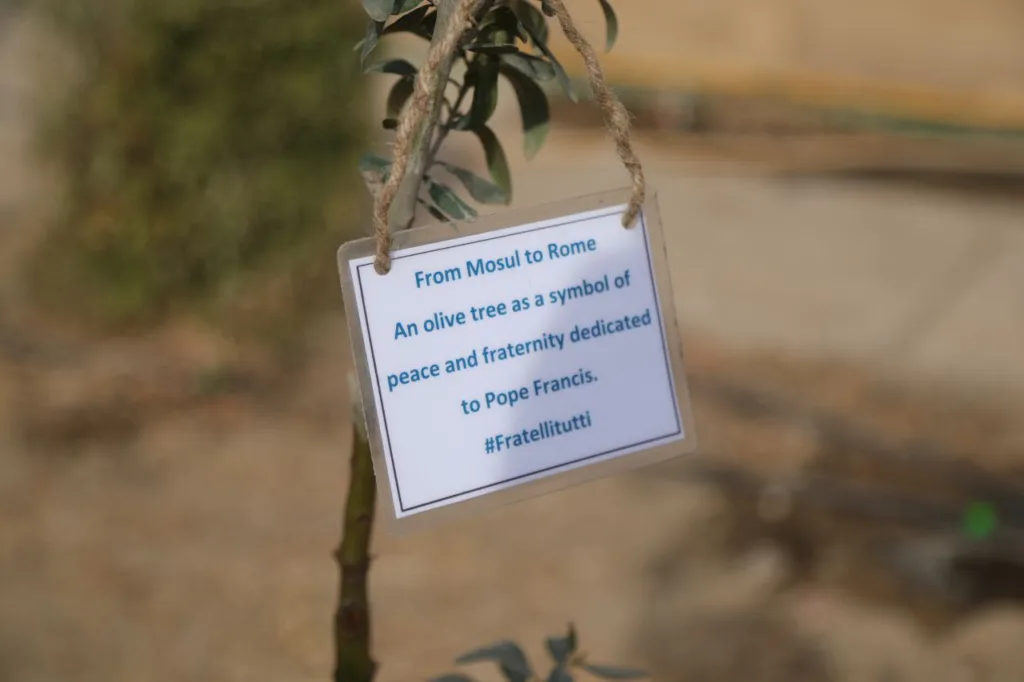

After two decades of violent conflict in the city of Mosul, Iraq, Dr Omar Mohammed, founder of the Mosul Eye organisation, started a tree-planting initiative to help bring communities together. In the United States, Dr Marc Zimmerman examined how greening and improvement initiatives reduced crime in cities that had suffered economic decline.

In this episode, Dr Omar Mohammed and Dr Marc Zimmerman, interviewed by Dr Nafees Hamid, discuss the role of greening initiatives in these two different contexts, exploring how they can promote peace, build trust between communities and authorities, and help to increase resilience against violent crime and extremism.

You can also listen on the War Studies podcast page, where this was originally released.

Beirut is the posterchild for a divided city.[i] 15 years of fighting during Lebanon’s civil war (1975-1990) saw the capital city split by ethnic, religious, and physical lines. These divisions did not end with the war. Over three decades later, sectarianism, segregation, economic inequality, and violence are a lasting part of Beirut’s post-war legacy.

The physical reconstruction of the city centre in post-war Beirut is believed to have played a role in these enduring divisions. When the reconstruction process began, many Beirutis saw it as an opportunity for society to heal. The public domain could be remade and revived, and in this way a space for reconciliation would be built.

Solidere building site in Beirut. Credit: Shutterstock/David Dennis

Instead, the work, which was carried out by the private company Solidere, has been accused of promoting a culture of ‘amnesia’ around the civil war, as well as exacerbating socio-economic divisions. When Solidere rebuilt Downtown Beirut, they sought to remove all physical remnants of the war. In their place, a shiny new imagined centre was built.

But burying traces of war does not necessarily mean the past is buried too – and failing to create a unified space may be contributing to a divided society.

Nejmeh Square in Downtown Beirut. Credit: Shutterstock/Sun_Shine

Solidere’s reconstruction process, which began shortly after the war ended, seemed set on destroying all traces of recent history, and streets and buildings quickly fell prey to the bulldozers. By 1993, 80 per cent of structures in Downtown were damaged irreparably – yet only a third of this had been caused by the war itself.[ii]

For many, Solidere’s reconstruction of Downtown is the embodiment of the state’s policy of amnesia. The Taif Accord signed in 1989 to formally end the civil war proclaimed that there was ‘no victor and no vanquished’ in Lebanon. It suggested no mechanism for dealing with the legacy of fighting, nor did it mention victims. By circumventing the issue of responsibility, the state could begin to move forward. At the same time, it encouraged a culture of forgetting, leading to accusations of a state-sponsored amnesia in the country. One activist noted that ‘the downtown is the core of the reconstruction ideology — that we don’t need to look at the past’.[iii]

It’s been claimed that, for ‘communities of difference’ to be successful, there must be a ‘studied historical absentmindedness’.[iv] Given a general amnesty law in 1991, a broadcasting censorship law in 1994, and a law in 1995 enabling ‘the missing’ to be classified as ‘dead’, it seems unlikely that remembering the past would yield justice in the present. This ‘amnesia’ could therefore help to promote harmonious co-existence.[v] For some, forgetfulness is seen as ‘an antidote to future conflict’.[vi]

Read the full blog on the ICSR website here.

South Sudan is highly susceptible to both protracted conflicts and the impacts of climate change. Before 2011, the country experienced a long and deadly civil war. Disputes continued after independence, with violence often spilling over across borders and into nearby countries. Local impacts of climate change (e.g., droughts, flooding) disrupt economic growth and community livelihoods, potentially contributing to conflict and destabilising the region. Climate adaptation and food security can therefore have important implications for reducing violence, particularly social conflicts that involve local ethnic militias, civil defence forces, and vigilantes.

To test these implications, I collected monthly information on climate adaptation and food security projects implemented by nongovernmental organisations in South Sudan and its bordering countries between January 2012 and December 2022. Such measures include, among others, planting more resilient crops, building dams and granaries, managing environmental resources such as grazing land or water reservoirs, and training locals in more effective sustainable food production.

Unfortunately, I did not find that these types of adaptation projects have any impact on social conflict or civil war. In fact, at least in South Sudan, there was the risk that they might be associated with more conflict. A project manager I interviewed provided one explanation: “South Sudan is a complex crisis country …[while] flooding and drought have led to displacements, people move into new geographies, and conflict scenarios shift.” In these complex situations, adaptation can exacerbate these dynamics, especially if the root cause is political or socioeconomic; or, as another local policy ethnographer explained, “you cannot just ask for a local solution and detach national politics from the local issues.”

However, I did find one interesting exception. Adaptation interventions that emphasised general preparedness – including, for example, efforts to plant more resilient crops, train locals in more effective sustainable food production, and create sharing tools for renewable resources like water – were associated with lower rates of social conflict, both within South Sudan and across the border.

Why might adaptation that emphasises general preparedness help in alleviating violence? One explanation builds on the nature of social conflict actors. Social conflict actors are more prevalent than military, police, or rebel groups in the region because they thrive in contexts of weakened or decentralised government. Because these actors are more dependent on locally-sourced crops and cattle, they may also be more sensitive to the effect of weather shocks upon these resources. Adaptation strategies that emphasise general preparedness can address – albeit imperfectly – a wider range of unexpected weather shocks, reducing the need for violent competition over scarce resources.

Another explanation emphasises the disruptions the civil war caused to local livelihoods. As one policy researcher explained, by emphasising specialised adaptation, “programming tends to incentivize specific livelihood strategies…which do not respond to local livelihood trajectories.” This can increase uncertainty about the future, considering climate change’s effects are hard to predict. In contrast, adaptation strategies that emphasise building general resilience can provide local communities with more flexibility, allowing them to choose whether to maintain traditional livelihoods or, if needed, adapt to new ones.

Regardless of which explanation is correct, the finding that adaptation programs that emphasise general preparedness may help reduce conflict illustrates how important it is to consider a broad set of direct and indirect outcomes when trying to tailor climate adaptations to conflict contexts.

Nevertheless, it can be hard to convince donors who fund adaptation that this approach makes sense. Donors have their own expectations when choosing which project to fund, which leads to “top-down” pressures that often do not conform well to the local realities, where social conflict poses a constant hardship. The problem is that, “[m]ost donors don’t understand the complexities…it’s really difficult to be able on the one hand to put a proposal that supports donor demand but on the other hand, is really context driven,” as one policy practitioner explained.

At the same time, it is imperative to convince donors that considering a wider range of outcomes will improve the chances of success. Understanding how interventions designed to support climate adaptation and promote food security can be tailored to local conditions in conflict settings is crucial. By investing in projects that have a better chance not only of improving adaptation in the immediate terms, but also of reducing the risk of violence, we can improve long term resilience, thereby preventing conflict from disrupting livelihoods and harming adaptation efforts.

Dr Omar Mohammed is a renowned historian and the voice behind ‘Mosul Eye’, a blog which anonymously documented life under Islamic State (IS) in the city of Mosul, Iraq. Today, the Mosul Eye Association focuses on promoting the recovery of Mosul and its cultural heritage, as well as empowering the city’s youth. The most important task Mosul Eye is undertaking is to promote Mosul globally to replace the negative image of the city after its fall to IS in 2014 and the subsequent destruction.

Hi Omar. Thanks for joining us. Please could you explain what Green Mosul is?

Green Mosul was an initiative started by Mosul Eye, and ultimately led by youth, to plant trees in the city of Mosul, but really it has two definitions. It refers to the greening initiative, which was the effort to repopulate Mosul with green space after the massive estruction that took place during the conflict. But it really aimed at, and can be defined as, an initiative to support reconciliation in post-war Mosul.

Following the conflict, there was a need to bring the people together, and to do that we needed to find something everyone could relate to. We wanted to disconnect them for a short time from the religious and social problems in the city, and we settled on one thing they could agree on: a tree. A tree doesn’t have a religion. It doesn’t have an ethnicity. It only has what benefits the community: clear, clean oxygen, a good view, and the ability to create a nice landscape.

Green Mosul ran from March 2022 to March 2023, and, in that time, we planted 9,000 trees in Mosul and the wider Nineveh province. When we started the initiative, we signed agreements with the local government and with the universities, and one of the terms was that they would commit to planting trees every year. Green Mosul has now technically ended, but the University of Mosul and the Technical University of Mosul continue to plant trees on an annual basis, and the local government has also dedicated a portion of the budget to planting trees every year. Our initiative didn’t stop when we finished our work. We wanted to make sure that it continued and that others could build on it.

Was it easy to get the support you needed to launch Green Mosul? How was the idea first received?

At the very beginning, we sought the support of the Iraqi government, but they wanted to see results before they got involved. I then approached the French government, as I knew they were interested in such initiatives. Their cultural attaché liked the idea, so I went away and developed the initiative amongst the community. One month later, the French government approved the idea, and Green Mosul was borne. Once we’d secured the funds, the local authorities were keen to support us, and we signed agreements with the forestry department, the municipality, the universities, and with other entities in the city. It became a fully Mosuli initiative, where the people and the government were working together for a common interest: the urban greening and, at the same time, the rehabilitation of the social fabric of the city.

Was it important for you to have the local authorities involved?

It was. One of the hurdles to post-conflict recovery in Iraq is that many people see the authorities as dysfunctional. I might agree with them, but I see that there is a way of utilising this dysfunctional government by making it functional – and the only way to make it functional is when you involve them. So Mosul Eye brought the Green Mosul initiative to the government, and they helped make it happen. We didn’t have cars to transport the trees, so we used the municipality’s cars. We didn’t have the ability to create the irrigation system for the trees we were planting, so we used the forestry department. I think their involvement also helped the initiative grow. Members of the public are not necessarily aware of what ‘social cohesion’ is, but they saw Green Mosul as a reliable initiative because of how many people were involved.

Through Green Mosul, we were also aiming to create trust between the authorities and the population. We wanted it to be a collective effort, because the initiative also focused on a very important principle, which is that the process of healing has to be collective in order for it to be strong and impactful. Mosul Eye helped the government to understand the critical importance of social cohesion and of rehabilitating the social fabric, but at the same time, the government gave us the equipment and the space. I think we contributed collectively, and that’s why I always say that this is an initiative of Mosul – it’s not just an initiative of Mosul Eye. It’s important to show the people that they have agency in the process of their healing. They need to own it.

What was the response like among the local community? Were people keen to get involved?

We had a specific communication strategy when we first approached the local communities. We made sure to keep the same distance with the community leaders and the public, because we didn’t want to create the impression that Green Mosul was only for elites. So we spoke to the Yazidis, to the Christians, to the Shia, to the Sunni, and to the endowment administrations of the Yazidis, the Christians, the Shia, and the Sunni. We made sure that the first communication was with the public, and then we facilitated their own communication with their community leaders. Once the locals initiated the conversation, the community leaders came to us, and asked to get involved.

In fact, one of the places where we planted trees was as a result of communication with a woman from Tel Keppe. She told us there was an empty park in the city, and the community wanted to use it to create a space for their children, but the land was owned by the church. It wasn’t easy to convince the church at that time, and distrust between the different religious communities was still strong. We were trying to avoid being labelled religiously – we were trying to be seen only as individuals who had an interest in rehabilitating these spaces – so I spoke to the head of the church and explained that it was a great space. The church would probably receive more visitors if people came to the public park, and everyone would be happy. The priest agreed, and we created a public space where there was both a religious site and a secular site. Today, the same priest is asking me for more trees to be planted.

Within the communities, we also started receiving offers from people saying they didn’t just want trees to be planted in their space, but they wanted to contribute trees to be planted elsewhere. One person also suggested that we plant trees for those lost during the conflict, and then everyone started coming forward with names. They wanted to put the name of their son or daughter, or their mother or father, with this tree or this tree. In the first few months, it was Mosul Eye and the municipality running Green Mosul, and then it became led by the people themselves.

Were the sites where the trees were planted important, or was it more about the process of bringing different communities together?

The two things were intertwined. Some of the sites we chose were religious, because we wanted to try and encourage young Muslims to go to Sinjar and plant trees around the worshipping place of the Yazidis, for example, and young Yazidis to go to Bashiqa or to Mosul and plant trees inside al-Nouri mosque and Al-Saa’a church. We tried to treat these sites holistically, so we communicated to the people of those faiths that we had an interest in their religious space, but, at the same time, they were also heritage sites and public spaces for the people. We did the same in the Shia, the Sunni, the Christian, and the Yazidi majority areas, but there was one condition: that a Yazidi plants in a Muslim side and a Muslim plants in a Yazidi side and so on.

Green Mosul also planted trees in heritage sites, and we had an agreement with UNESCO, whose supervision those sites were under. We planted trees in their sites, but on the condition they would become part of the public space. We always tried to make sure that the planting of trees was seen as being outside the lens of religion – it was a holistic approach that involved everyone.

You mentioned distrust between religious communities earlier – was it difficult to persuade a person from one religion to plant trees at the religious site of another?

At the beginning, it was difficult, and sometimes we needed to have difficult conversations. But we also trained around 25 people from all communities to use as the face of the initiative. They would reach out to their communities, and they would explain that they were there wishing no harm, but they were there to contribute to the community. And when people saw the results – when they went to a place with no trees and when they went back and saw the trees planted – they understood. After a short time, things went smoothly.

When you started Green Mosul, what did you hope the outcome would be?

To be honest, when we started, I had fears it would not succeed. Given the gravity of what had happened in the city, I was concerned people might not be interested. But we started Green Mosul with three goals. One was that we would create a sense of responsibility among the people. Many had become disconnected from the city as a result of what had happened since 2003, and we wanted to reintroduce a sense of responsibility among citizens to contribute to their city. Our second aim was to introduce a mechanism of communication between communities that wasn’t about religion or ethnicity. The third was to create trust between the government and the public. I still make sure I communicate everything I do with the government, and then I communicate this to the public. I wanted to reintroduce the meaning of governance. I wanted the public to know the government is not just people sitting behind closed doors, but that they themselves can gain access to them and work with them.

We’ve achieved those three things, but we’ve also created friendships between different communities. They still visit each other, they are friends with each other, and they are still communicating. These different communities are working together, and that’s what we aimed to do, and we succeeded. I’m so happy about the results. I’m so happy about the involvement of the community. I’m so happy that we were able to do this in a complicated context, where people are still healing. This means there is potential for people to work together in Mosul to create a sustainable future for themselves, but it will take time.

The other element we introduced is that we raised awareness about climate change in a very complicated context – imagine talking about climate change in a city that is heavily destroyed and where people are still missing. But Green Mosul succeeded in introducing the conversation around climate change, and the university is now running research and attracting more researchers to work on the subject. One topic which is dear to me is what I call ‘green heritage’. I saw the impact of the destruction of cultural heritage on the people and the potential conflicts that it might create, and I realised that, although Islamic State might not come back, there is another enemy: climate change. It’s important to address this when we speak about preserving cultural heritage. The recovery of Mosul’s cultural heritage plays an important role in the collective healing from generational trauma, and it gives hope to the people that social cohesion is still possible as well as limiting the impact of radicalisation.

It sounds like Green Mosul has been a great success. How important do you think it is to have grassroots-led vs authority-led initiatives in Mosul?

I think encouraging the grassroots to lead more initiatives is fundamental for a healthy rehabilitation of Mosul, because not all recovery efforts succeed in meeting the results they intend. A quick rehabilitation might bring the opposite outcomes, so it’s important to create a sense of responsibility among the grassroots so they feel they have a say in what’s happening. Now is the right time to work on this, and invest in this, because we are still in the process of rebuilding and healing. It’s the best time frame we have to enable people to develop this sense of responsibility.

At the same time, we shouldn’t ignore the government. The government can always contribute, and opportunities can always be created if there’s a will, a sense of responsibility, and most importantly, diplomatic expertise – because it’s all about how you communicate your ideas in a post-conflict environment.

In Mosul, we need less focus on religion. When rehabilitation efforts target certain religious groups, they’re not talking about justice for all. They’re just reinforcing divisions. Create the space, and let people be the way they want. I think let’s talk more about trees than religion. You can plant trees in a mosque or in a church, but it doesn’t have to be because they’re a mosque or a church. It can be because you care about the environment or because you simply want to enjoy green space.

You can read more about XCEPT’s research on reconciliation initiatives in Iraq here: Iraqi heritage restoration, grassroots interventions and post-conflict recovery: reflections from Mosul

When conflicts arise around fragile or contested borders, there are knock on effects that impact local, national and regional economies, as well as relationships between state and non-state actors. XCEPT’s Local Research Network partners are studying examples of such disruptions in different regions. In Syria, Kheder Khaddour looks at the northern region, where the border with Türkiye represents a lifeline for the millions of people displaced by Syrian civil war. Azeema Cheema studies the shifting relationship between authorities in Pakistan and Afghanistan since the Taliban’s takeover, and the effect on trade and migration policies at their shared border. Lastly, Ahmed Musa explains what’s been happening in Las Anod, a major trading hub in the Horn of Africa that has been destabilised by competing actors vying for influence.

Disclaimer: The opinions, findings, and conclusions stated herein are those of the speakers and do not necessarily reflect those of the partner organizations or the UK government.

Bangladesh is facing a climate emergency. Although it is one of the world’s least polluting nations, it is already experiencing some of the most severe effects of changing weather patterns. The country lies close to sea level, and much of the land is river delta that is prone to seasonal flooding, erosion, and salinity intrusion and faces the risk of devastating cyclones, all of which can be catastrophic for local communities and their livelihoods. Many families are unable to recover from such climate disasters and are forced to move to other parts of Bangladesh or across borders to rebuild their lives.

Unsurprisingly, Bangladesh has become a prominent voice in global conversations about climate change and the need for international responsibility-sharing. Developing nations generally shoulder an outsized share of the costs of climate change compared to wealthier nations, a fact recently recognised in global forums such as the United Nations Climate Change Conference, which convenes the annual Conference of Parties, or COP. In its 27th sitting, in 2022, the COP established a loss and damage fund for vulnerable countries, which was operationalized a year later at COP 28. While proponents celebrated this as a win, many practical challenges remain, including raising sufficient funds and figuring out how to measure losses and distribute resources equitably among nations. The many intersecting consequences of environmental degradation require long-term solutions and a holistic approach. Mechanisms like the loss and damage fund will not increase climate resilience if social, political, and economic factors are not considered alongside the environmental ones. Migration and displacement of affected populations is one of the most significant consequences of climate change. Along with the downstream impacts on labor markets, social networks, and transnational relationships, these will need to be accounted for in national and international climate strategies and development policies.

As “ground zero” for a shifting climate that is turning many environments inhospitable, Bangladesh offers a case study of these overlapping vulnerabilities. In parts of the borderlands with India, longstanding social and political fragilities lie beneath the new environmental stressors. The border itself has been an historical point of contention between the two countries, and security measures in the past have led to violence. The distance from central governance institutions in Dhaka can result in border regions being underrepresented in national climate strategies, including the distribution of resources, which can further marginalize ethnic and religious minorities within border communities. The risks from climate change in such areas of existing vulnerability cannot be overstated: economic instability, food insecurity, unreliable access to justice, and increased inequalities that can trigger communal violence.

Attempts to institutionalise sustainable solutions in climate-vulnerable areas must be rooted in a situated understanding of how communities experience and respond to environmental disruptions. Outsiders may struggle to grasp these nuances, which can lead to poor planning and interventions that cause further harm. In southwestern Bangladesh, for example, seasonal and informal migration to urban centers in India have become more and more of a survival mechanism for those who have lost their agricultural livelihoods. This can clash with policies that regulate cross-border movement, including the steady increase in border fencing. Researchers and practitioners working in affected areas can play an important role in collecting information and building evidence that speaks to local experiences, but this must be done with sensitivity and recognition of the power dynamics of classical research settings. Historically, the study of vulnerable populations in particular has been steeped in inequality and defined by an essentially extractive relationship between researchers and researched.

As the world mobilises to support climate adaptation and resilience, decision-makers need analysis that reflects the needs and priorities of communities at the forefront of climate change. The Asia Foundation is working with the Centre for Peace & Justice (CPJ) of BRAC University in Bangladesh to develop a framework for assessing how existing drivers of fragility interact with the onset of climate change, in order to understand the risks for future climate resilience and development programming in the country. The Foundation’s partnership with CPJ originates in the UK-funded development research program XCEPT, Cross-Border Conflict: Evidence, Policy, and Trends, which works with local researchers to provide analysis of conflicts in border regions that is grounded in the affected communities.

With support from this program, CPJ has developed a new methodology for community-driven data collection, based on “participatory research,” that seeks to avoid the vertical power dynamics inherent in traditional research models. CPJ first employed this methodology among the Rohingya refugees seeking asylum in the Bangladeshi coastal town of Cox’s Bazar, on the border with Myanmar. A network of researchers drawn from within the refugee community itself enabled the affected population to become co-producers of knowledge and solutions, building trust between aid providers and recipients and strengthening the credibility of the research findings. The insights this yielded have helped foreign donors and humanitarian agencies operating in the world’s biggest refugee camp to work more effectively. This approach is a major contribution to localising aid, as it shifts power over information towards the affected populations.

This year, CPJ is piloting the same research approach in southwestern Bangladesh, applying it to the question of how climate adaptation strategies reflect and respond to broader social and political fragilities in the local context. A scoping study first undertaken by the team in 2022 determined that this question is a major factor in the long-term success of such strategies. Subsequently, a research project was designed replicating the approach used in Cox’s Bazar, starting with the recruitment and training of young people to work as “community researchers.”

The team faced some initial challenges: refugee camps are an entirely different operational context than areas of the general population, because of the institutional control within the camps and the relative immobility of the camp population. Furthermore, the severity of the refugee crisis in Cox’s Bazar was a powerful motivator for camp residents to participate. In southwestern Bangladesh, on the other hand, researchers wondered how to build interest among local youth in participating in the data collection and how to encourage respondents to open up about their experiences and aspirations. Researchers have also reflected that the obstacles facing Rohingya refugees in their fenced camps are immediate and tangible, while slow-onset climate factors that distress and uproot communities in climate-affected border towns are less immediately apparent.

To apply a proven methodology in a completely new context, both major and seemingly minor aspects of the research study may need to be revised. CPJ’s community-based research approach acknowledges the complexity and unique social order of the borderlands, allowing for a more comprehensive understanding of the study sites. Climate realities around the world are not equal. These locally grounded methods of exploration avoid the mistakes of knowledge systems that force top-down assumptions on local communities, and instead empower them to be the voices of their own experience.

The initial phase of this new project is nearing completion, and community researchers are receiving training for the first round of data collection. From where we stand now, there is much to discover, to learn, and to unlearn, and we hope to do it together.

Tabea Campbell Pauli is a senior program officer with The Asia Foundation’s XCEPT program, and Tasnia Khandaker Prova is a research associate with the Centre for Peace and Justice of BRAC University. They can be reached at [email protected] and [email protected], respectively. The views and opinions expressed here are those of the authors, not those of The Asia Foundation.