In August 2022 it will be five years since the start of one of the world’s most severe humanitarian crises, yet the political and security dynamics surrounding Rohingya refugees in Bangladesh remain unstable. Persecution and targeted attacks against this minority community by Myanmar’s military led to the forced displacement of over 730,000 refugees across the border into Bangladesh in 2017. Five years on, their lives continue to be marked by struggle.

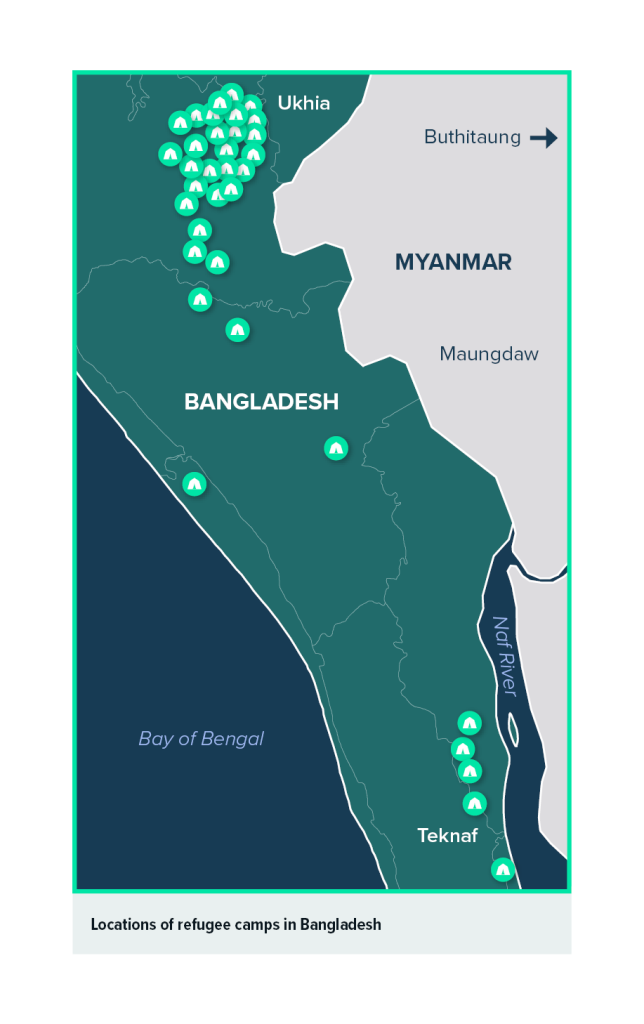

Bangladesh’s own history of war may have influenced its government’s openness to refugees, but growing uncertainty in a post-Covid world, anti-Rohingya sentiments amongst the population, security concerns, and pressure on resources are cited as reasons for a recent rise in restrictions on residents of the 34 refugee camps along the border. These restrictions relate to refugees’ uninterrupted access to education, employment, movement, and civic participation in their host country. Underdevelopment, poverty, crime, and trafficking in people and drugs affect both the Rohingya and the host communities adjacent to the camps.

Despite vocal demands by Rohingya to be able to return to their home villages, organised repatriation attempts have been hindered by lack of political will in Myanmar. Today, global humanitarian aid is on the decline as the international community contends with the need to address competing crises. Refugees and local communities are angered by the limited efforts of global powers to compel Myanmar to accelerate Rohingya repatriation. Increased frustration amongst Bangladeshi authorities has translated into harsher policies and limited opportunities for the refugees. Amid pressure to uphold refugee rights, and the need to maintain safety and adequate infrastructure within the camps despite a persistent funding shortage, actors involved in the response face increasing challenges around sustainable solutions for Rohingya populations.

The Asia Foundation’s partner in Bangladesh, Centre for Peace and Justice, Brac University, (CPJ) has worked to address emerging concerns amongst Rohingya and host communities, and analyse social differences and political dynamics through various research initiatives that aim to understand and elevate voices on the ground. This article summarises viewpoints of Rohingya refugees on their current predicament and outlook, compiled by CPJ researchers since 2018.

Camp governance and decision-making mechanisms have been criticised by human rights groups for being unclear, restrictive and ad-hoc. With an ever-shifting regulatory dynamic, limited direct access to policymakers, and a national refugee policy vacuum that allows lower-level officials to apply rules at their own discretion, the governance environment in Cox’s Bazar remains opaque, complex and exclusive of community voices. Humanitarian agencies focus on maintaining permission to work in the camps and are hesitant to intervene and probe officials about policies. It is unclear to communities how decisions about refugee policy are made within government and by whom, resulting in a power gap and lack of accountability toward stakeholders.

Who is making decisions and why are they unknown to our community?

a Rohingya refugee in Bangladesh

Livelihood possibilities in the camps are extremely limited. Rohingya are restricted from moving from one camp to another and have no right to formal employment or access to markets. Even the need to travel for medical attention requires the permission of camp authorities. Hundreds of makeshift shops have been destroyed by authorities in recent months, limiting refugees’ access to basic necessities not provided as aid, including many cooking ingredients as well as clothing.

Perceptions of the Rohingya amongst host communities are generally negative even though, according to CPJ’s research, only a small percentage of host community residents have personally interacted with a refugee. Local people fear the assimilation of refugees and the increased pressure on already-stretched resources. Negative impacts on wage rates and over-saturation of the labour market have been contentious issues.

Education gaps among Rohingya children and adolescents remain unresolved. Approximately 400,000 school-aged refugees are not enrolled in formal schooling, and although a pilot formal education programme was recently launched when schools reopened post-Covid, it serves only a small percentage of learners and many will likely never return to their studies. Moreover, private learning centres organised by the Rohingya have been restricted by authorities, eliminating educational access for thousands more children.

Global attention has been fleeting. The spotlight that brought attention to the Rohingya crisis after the 2017 exodus has shifted elsewhere, and Rohingya feel that they are isolated from the international community. Bangladesh continues to be praised by the international community for hosting persecuted Rohingya and undoubtedly saving thousands of lives, but refugees are frustrated with the lack of public discussion around their current situation. Many claim that living conditions within the camps have deteriorated leading to desperate attempts by refugees to escape, akin to their pre-exodus state of vulnerability in Myanmar. High-profile international delegations have resumed visiting the camps, but few visits have resulted in tangible action toward the necessary changes.

Sustainable, long-term solutions for displaced Rohingya will require a comprehensive refugee policy in Bangladesh, built on accountability to affected populations and effective coordination amongst national and international actors. Such a policy will need to address concurrent needs for good governance, refugee rights and participation, humanitarian service provision, and security-related factors, grounded in robust data reflecting the evolving needs and perspectives of refugee and host populations. Political economic analysis can be used to assess the current policy environment, highlighting gaps that need to be addressed, an understanding of how decisions are made and enforced, and identifying areas for innovative approaches to refugee governance. For example, Rohingya participation in labour markets could be approached in a way that benefits refugees and impoverished Bangladeshis alike. Such a coordinated, inclusive approach may yet yield opportunities for improvement.